VectorWare has developed a method to run Rust's standard library on GPUs by implementing a hostcall framework that bridges GPU code to host CPU operations, enabling developers to use familiar Rust abstractions for GPU programming while maintaining performance and safety.

The fundamental promise of Rust has always been its ability to provide high-level, safe abstractions over low-level hardware control. For years, this promise has been largely confined to the CPU, while GPU programming remained a domain of specialized, performance-obsessed code written in languages like CUDA or OpenCL. VectorWare's recent breakthrough—enabling Rust's standard library to run on GPUs—represents a significant shift in this landscape, effectively extending Rust's abstraction boundary across the heterogeneous computing divide.

At its core, the challenge stems from Rust's layered library architecture. The language's standard library (std) sits atop core and alloc, adding operating system concerns like file I/O, networking, and threading. GPUs, lacking a traditional operating system, have historically required the #![no_std] annotation, forcing developers to work with only the foundational core library. While this enabled Rust in embedded and firmware contexts, it created a stark divide for GPU programming. The vast ecosystem of crates.io libraries that depend on std became inaccessible, and developers lost access to ergonomic abstractions that make Rust productive.

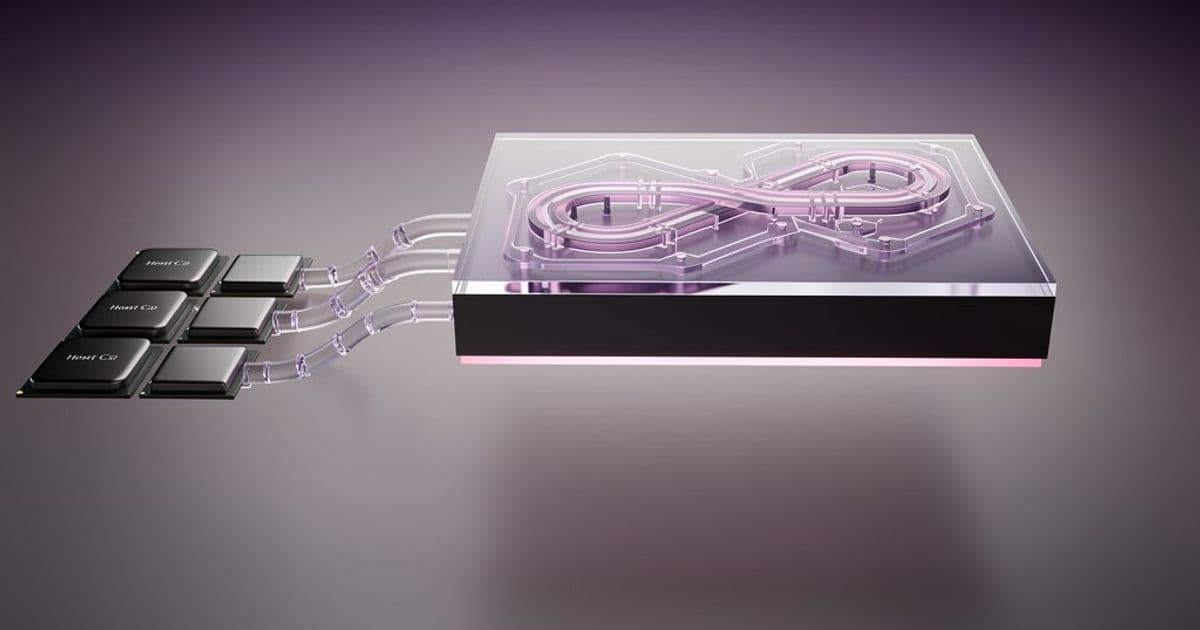

VectorWare's solution is a hostcall framework that functions as a structured request system from GPU code to the host CPU. Conceptually similar to a syscall, a hostcall allows GPU kernels to delegate operations they cannot perform themselves to the host, which executes them using its operating system APIs and returns results. The beauty of this approach lies in its transparency: to the end developer, Rust's standard library APIs appear unchanged. A call to std::fs::File::create on the GPU behaves exactly as it would on the CPU, but under the hood, it issues an open hostcall to the host, which performs the actual filesystem operation.

The implementation details reveal careful engineering for both correctness and performance. The hostcall protocol is deliberately minimal to keep GPU-side logic simple, employing techniques like double-buffering and atomic operations to prevent data tearing and ensure memory consistency. Results can be packed to avoid GPU heap allocations where appropriate, and CUDA streams are leveraged to prevent the GPU from blocking while the host processes requests. Importantly, the host-side handlers are implemented using Rust's std themselves, making them portable and testable rather than acting as 1:1 libc trampolines. The team has even run a modified version of the hostcall runtime under Miri (Rust's memory safety checker) with CPU threads emulating GPU execution to verify soundness.

What makes this approach particularly elegant is its progressive enhancement capability. The term "hostcall" is somewhat of a misnomer, as requests can be fulfilled on either the host or the GPU depending on hardware capabilities. For instance, std::time::Instant can use a device timer like CUDA's %globaltimer on platforms that support it, while std::time::SystemTime—which requires wall-clock support—remains host-mediated. This flexibility enables advanced features like device-side caches (avoiding repeated round-trips) and filesystem virtualization, where the GPU maintains its own view of the filesystem and syncs with the host as needed. The framework even allows for innovative semantics, such as writing files to /gpu/tmp to indicate they should remain on the GPU, or making network calls to localdevice:42 to communicate with specific warp/workgroup 42.

The timing for this innovation is particularly apt. Modern GPU workloads, especially in machine learning and AI, increasingly require fast access to storage and networking. Technologies like NVIDIA's GPUDirect Storage and GPUDirect RDMA are making it possible for GPUs to interact more directly with disks and networks in datacenters. Consumer hardware is following suit, with systems like NVIDIA's DGX Spark and Apple's M-series devices bringing similar capabilities to desktop environments. As CPUs and GPUs converge architecturally—evidenced by AMD's APUs and the integration of NPUs and TPUs into various CPUs—the case for sharing abstractions across devices becomes stronger. Treating GPUs as isolated accelerators with entirely separate programming models is becoming increasingly anachronistic.

This convergence makes Rust's standard library an ideal abstraction layer for the GPU ecosystem. Unlike the mature CPU ecosystem, GPU hardware capabilities are changing rapidly, and software standards are still emerging. Rust's std can provide a stable surface while allowing the underlying implementation to adapt. The same GPU code could use GPUDirect on one system, fall back to host mediation on another, or switch between unified memory and explicit transfers depending on hardware support, all without requiring changes to user code.

VectorWare's work builds upon substantial prior art from the CUDA and C++ ecosystems. NVIDIA ships a GPU-side C and C++ runtime as part of CUDA, including libcu++, libdevice, and the CUDA device runtime, which provide implementations of large portions of the C and C++ standard libraries for device code. However, these are tightly coupled to CUDA, C/C++-specific, and not designed to present a general-purpose operating system abstraction. Facilities like filesystems, networking, and wall-clock time remain host-only concerns exposed through CUDA-specific APIs. Experiments like libc for GPUs have attempted to provide a C or POSIX-like layer for GPUs by forwarding calls to the host, but VectorWare's approach differs in two key ways: it targets Rust's std directly rather than introducing a new GPU-specific API surface, and it treats host mediation as an implementation detail behind std, not as a visible programming model.

The implications extend beyond technical implementation. By bringing the GPU to Rust rather than just bringing Rust to the GPU, VectorWare is enabling a new class of GPU-native applications where higher-level abstractions are critical. The example kernel they provided demonstrates this clearly: GPU code can now print to stdout, read user input, get the current time, and write to files—operations that were previously impossible or required convoluted workarounds. This unlocks a much larger portion of the Rust ecosystem for GPU use and significantly improves developer ergonomics.

As the VectorWare team includes multiple members of the Rust compiler team, they are keen to work upstream and open source their changes. However, changes to Rust's standard library require careful review and take time to upstream. One open question is where the correct abstraction boundary should live. While their current implementation uses a libc-style facade to minimize changes to Rust's existing std library, it's not yet clear that libc is the right long-term layer. The hostcall mechanism is versatile enough that std could be made GPU-aware via Rust-native APIs, potentially offering greater safety and efficiency than mimicking libc, though this would require more work on the std side.

This work represents more than just a technical achievement; it signals a philosophical shift in how we think about heterogeneous computing. As GPU hardware continues to evolve and converge with CPU architectures, the need for unified programming models that span different processing units becomes increasingly urgent. Rust's ownership model, zero-cost abstractions, and safety guarantees make it uniquely positioned to bridge this gap. By extending Rust's standard library to the GPU, VectorWare isn't just enabling new functionality—it's reimagining what GPU programming can be when freed from the constraints of specialized, low-level APIs and empowered with the same high-level abstractions that have made Rust transformative on the CPU.

The path forward involves deeper technical dives into the hostcall implementation, compiler work, testing and verification efforts, and broader thoughts on the future of GPU programming with Rust. As GPU hardware and software continue to mature, the progressive enhancement capabilities of this framework will become increasingly valuable, allowing applications to adapt to new hardware capabilities without code changes. This work lays the foundation for a future where developers can write complex, high-performance applications that leverage the full power of GPU hardware using familiar Rust abstractions, treating heterogeneous systems as a unified computational fabric rather than a collection of isolated accelerators.

Comments

Please log in or register to join the discussion