A deep dive into using a large language model to develop a custom compression algorithm for baby monitor sensor data, achieving a 53.6x compression ratio while navigating the challenges of LLM-generated code and benchmarks.

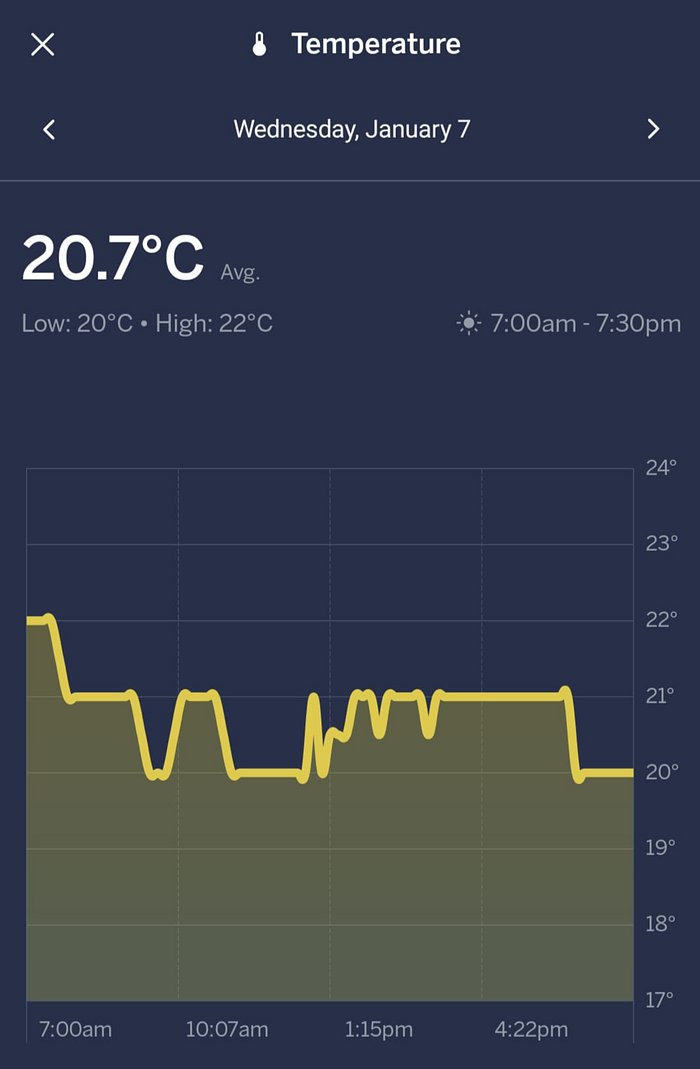

The challenge of storing high-frequency sensor data for infrequent queries presents a classic engineering trade-off: storage efficiency versus query performance. For a baby monitor company ingesting temperature and humidity readings every five minutes from thousands of devices, the standard approach—storing everything in a relational database—was becoming costly and inefficient. The data, while voluminous, was rarely accessed and served a single purpose: rendering graphs for mobile clients. This specific use case demanded a tailored solution, one that could compress the data dramatically while allowing for constant-time appends and preserving the temporal structure of the series.

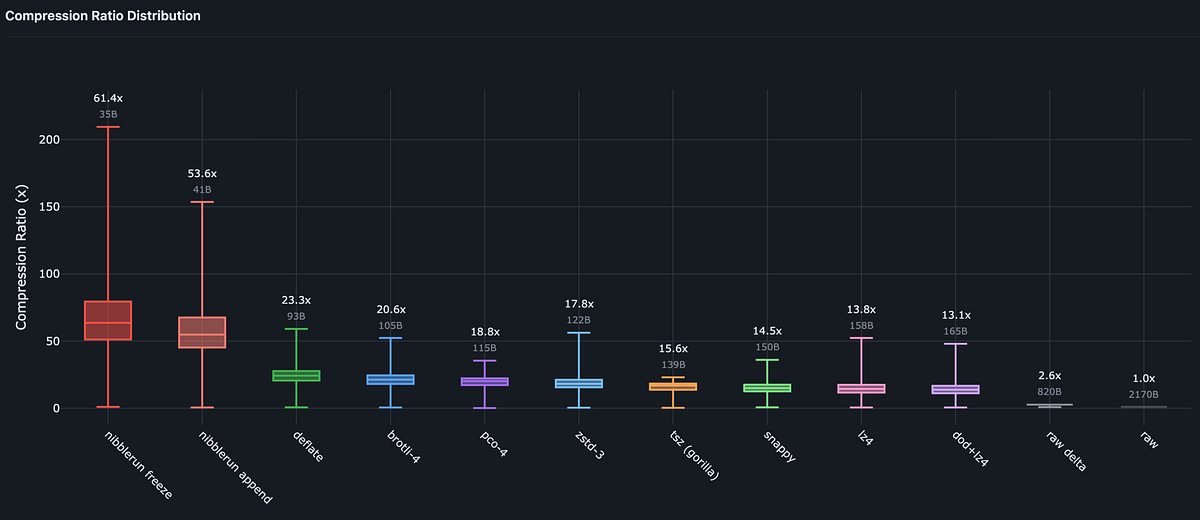

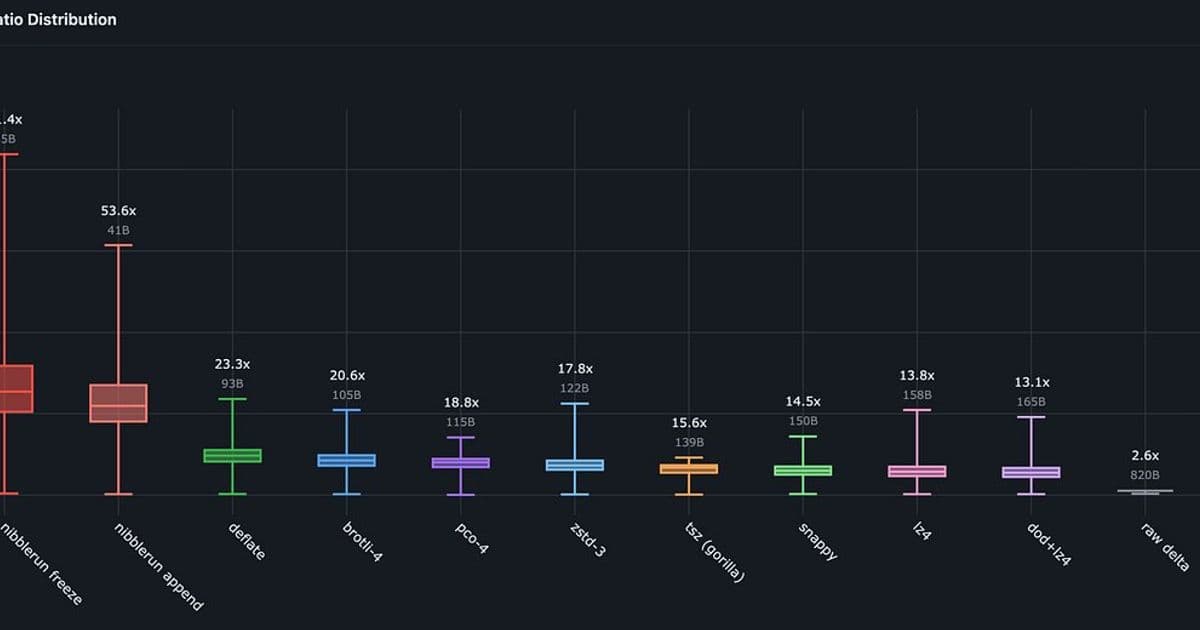

The core data structure was deceptively simple: each reading consisted of a 32-bit timestamp and an 8-bit integer value, totaling 5 bytes per reading. With a retention period of seven days at five-minute intervals, this amounts to 288 readings per device per day. For a fleet of thousands, the uncompressed storage quickly balloons. The initial investigation into standard time-series compression algorithms like PCO L4 and TSZ (Gorilla) showed promise, compressing a day's worth of data from approximately 3,270 bytes down to 127-140 bytes. However, these methods presented a critical flaw for the operational requirements: they were not appendable in O(1) time. Re-encoding the entire series for each new reading would be prohibitively slow, given the high insert rate.

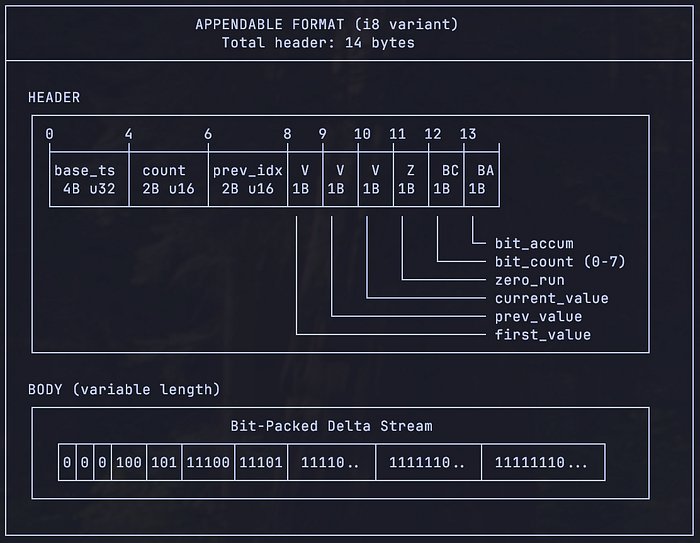

This limitation prompted the development of a custom algorithm, NibbleRun, designed in collaboration with an LLM. The algorithm exploits the domain-specific characteristics of the data: integer values that change slowly, a predictable 5-minute interval, and a high frequency of repeated values. The foundation is Run-Length Encoding (RLE) for zero deltas—the most common occurrence when temperature remains stable. Instead of storing a fixed number of bits for each run length, NibbleRun uses a variable-length encoding scheme that allocates fewer bits to more common run lengths. For instance, individual zero deltas are encoded in just 1 bit, while longer runs of 8-21 zeros use 9 bits.

Beyond zero-runs, the algorithm handles non-zero deltas and gaps with similarly optimized, variable-length encodings. The most common delta of ±1 is encoded in 3 bits, while larger deltas use progressively more bits. Gaps in data transmission, often just a single missed interval, are encoded in 3 bits, with larger gaps using 14 bits. A key optimization is timestamp quantization: since readings arrive at a near-constant 5-minute interval, storing a base timestamp and deriving subsequent timestamps from a fixed interval saves significant space. Gaps are explicitly marked to ensure correct timestamp reconstruction.

The final representation consists of a compact header (containing base timestamp, first value, and encoder state) and a bit-packed body of commands (zero-runs, deltas, and gaps). The appendable design maintains a small in-memory state, flushing to the bit-packed body only when necessary, ensuring O(1) appends. This design yielded a compression ratio of 53.6x for the appendable format, reducing a day's data from 2,170 bytes to just 40 bytes. A non-appendable "frozen" format for historical data achieves an even higher 61.4x ratio.

The development process, however, was fraught with challenges stemming from the LLM's role. While the LLM accelerated initial exploration and provided a wealth of ideas, it also introduced significant errors. The author encountered inconsistent benchmarks, where the LLM would measure different data subsets or use incorrect assumptions about data sizes. Validation logic was often incomplete, requiring manual correction. The LLM also tended to "hallucinate" performance metrics, estimating sizes instead of measuring them, and would sometimes change critical parameters without instruction, breaking unit tests. This experience underscores a critical lesson: treating an LLM as a junior engineer requires rigorous oversight, small incremental changes, and robust testing.

Testing was paramount. The author employed a multi-faceted approach: unit tests for core logic, property-based fuzzing with cargo-fuzz to uncover edge cases like overflows, and custom visualization tools to inspect the encoded bitstreams visually. These visualizations were instrumental in identifying inefficiencies, such as oversized state variables or suboptimal gap encoding, leading to further optimizations.

The final algorithm, NibbleRun, is a testament to the power of domain-specific optimization. It demonstrates that for specialized workloads, abandoning generic solutions in favor of a custom-built tool can yield orders-of-magnitude improvements. The algorithm is now available as an open-source Rust crate on GitHub and crates.io, offering a practical solution for similar time-series compression problems.

Ultimately, the project highlights a nuanced relationship between human engineers and AI assistants. The LLM served as a powerful catalyst for ideation and initial implementation, but its limitations necessitated a skeptical, methodical approach. The journey from a generic compression benchmark to a highly optimized, appendable algorithm illustrates that while AI can expand the realm of what's possible, human expertise remains essential for navigating complexity, ensuring correctness, and refining solutions to meet precise operational demands.

Comments

Please log in or register to join the discussion