Recent academic claims have sparked debate about whether large language models are fundamentally surjective, injective, or even invertible. We break down these mathematical concepts and clarify what they actually mean for AI safety, privacy, and the future of generative models.

Mathematical Properties of LLMs: Surjectivity, Injectivity, and What They Really Mean for AI Safety

Recent academic claims have sparked intense debate about the fundamental mathematical properties of large language models. Two papers published in quick succession—one suggesting Transformers can output anything given appropriate input (surjective), another claiming LLMs always map different inputs to different outputs (injective)—have led to wild speculation about the implications for AI safety, privacy, and the very nature of these models.

Are jailbreaks fundamentally unavoidable? Are LLMs lossless compression of knowledge? Do we have no privacy when using these systems? Do these properties together imply LLMs are bijective? In this article, we clarify the concepts of surjectivity, injectivity, and invertibility as they apply to large language models and explain their true implications for the AI landscape.

Understanding the Mathematical Foundations

To properly evaluate these claims, we first need to understand the underlying mathematical concepts. Let's consider a function $f:\mathcal{X}\to\mathcal{Y}$ that maps inputs from set $\mathcal{X}$ to outputs in set $\mathcal{Y}$.

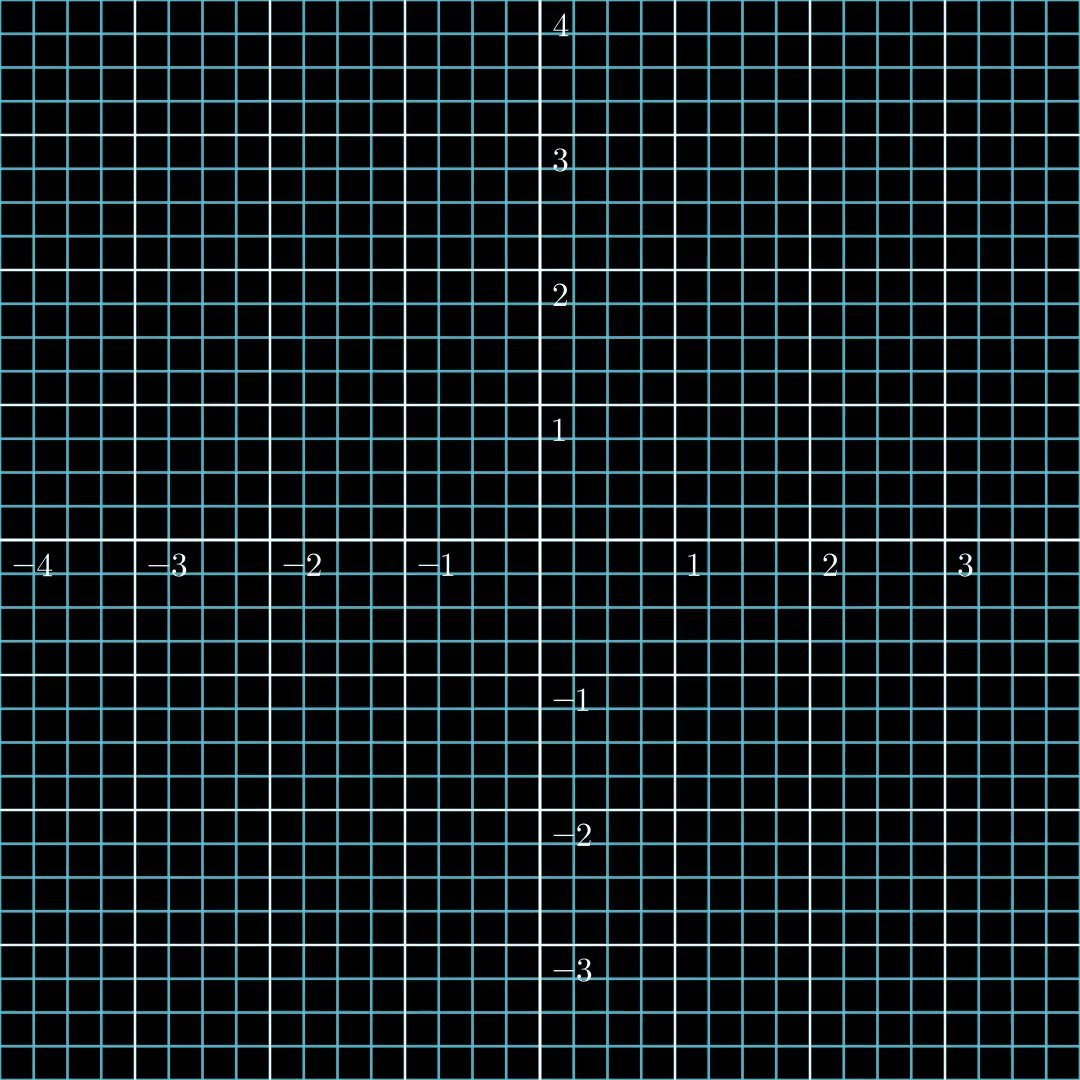

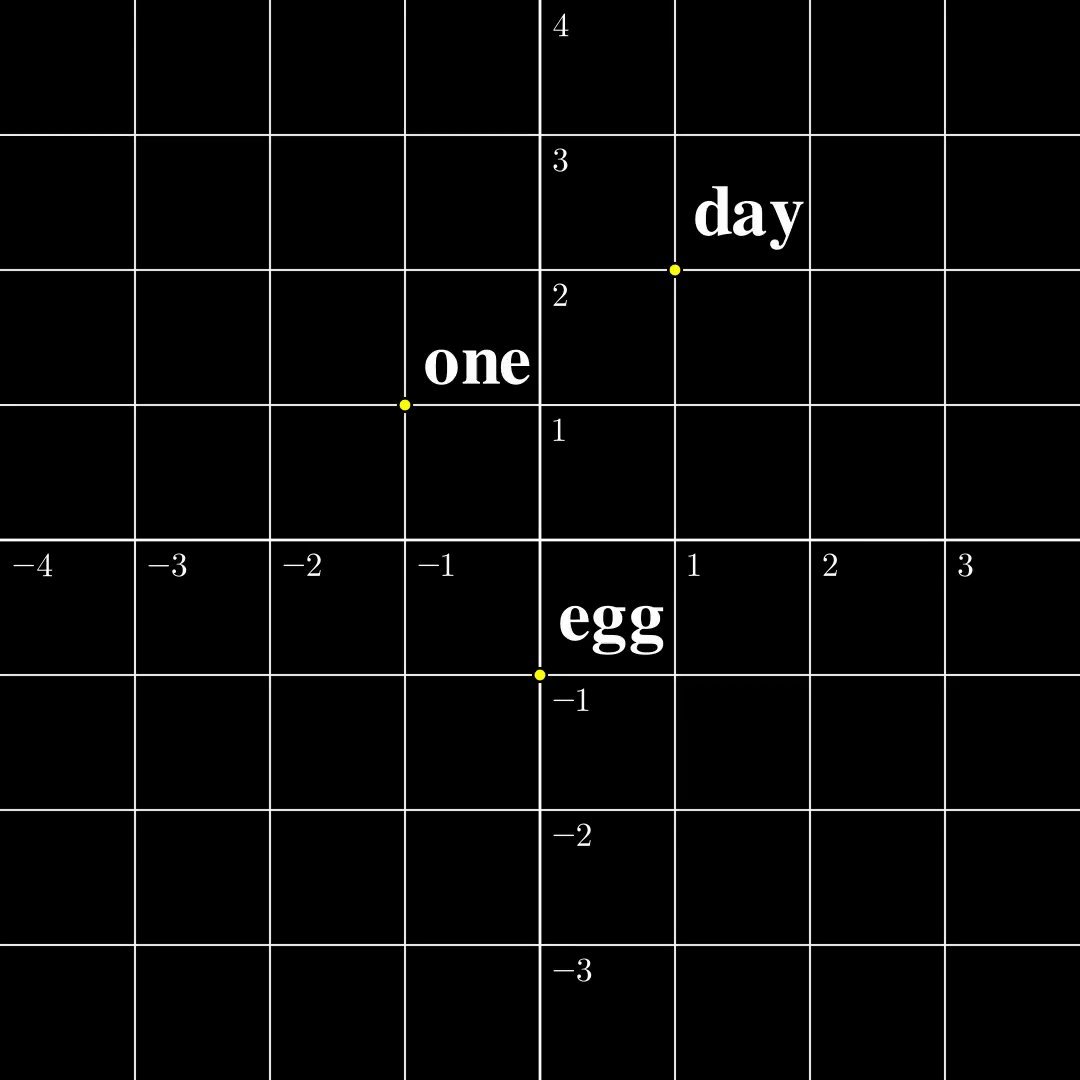

Figure 1: A surjective function. The output covers the whole space, while self-crossing.

Figure 1: A surjective function. The output covers the whole space, while self-crossing.

Surjective Functions

A function is surjective (or "onto") if for every element $y$ in $\mathcal{Y}$, there exists at least one element $x$ in $\mathcal{X}$ such that $f(x) = y$. In other words, every possible output is reachable from some input.

For LLMs, if we consider the model as a function $f$, surjectivity would mean that any conceivable output—harmful or otherwise—could be generated given some input prompt.

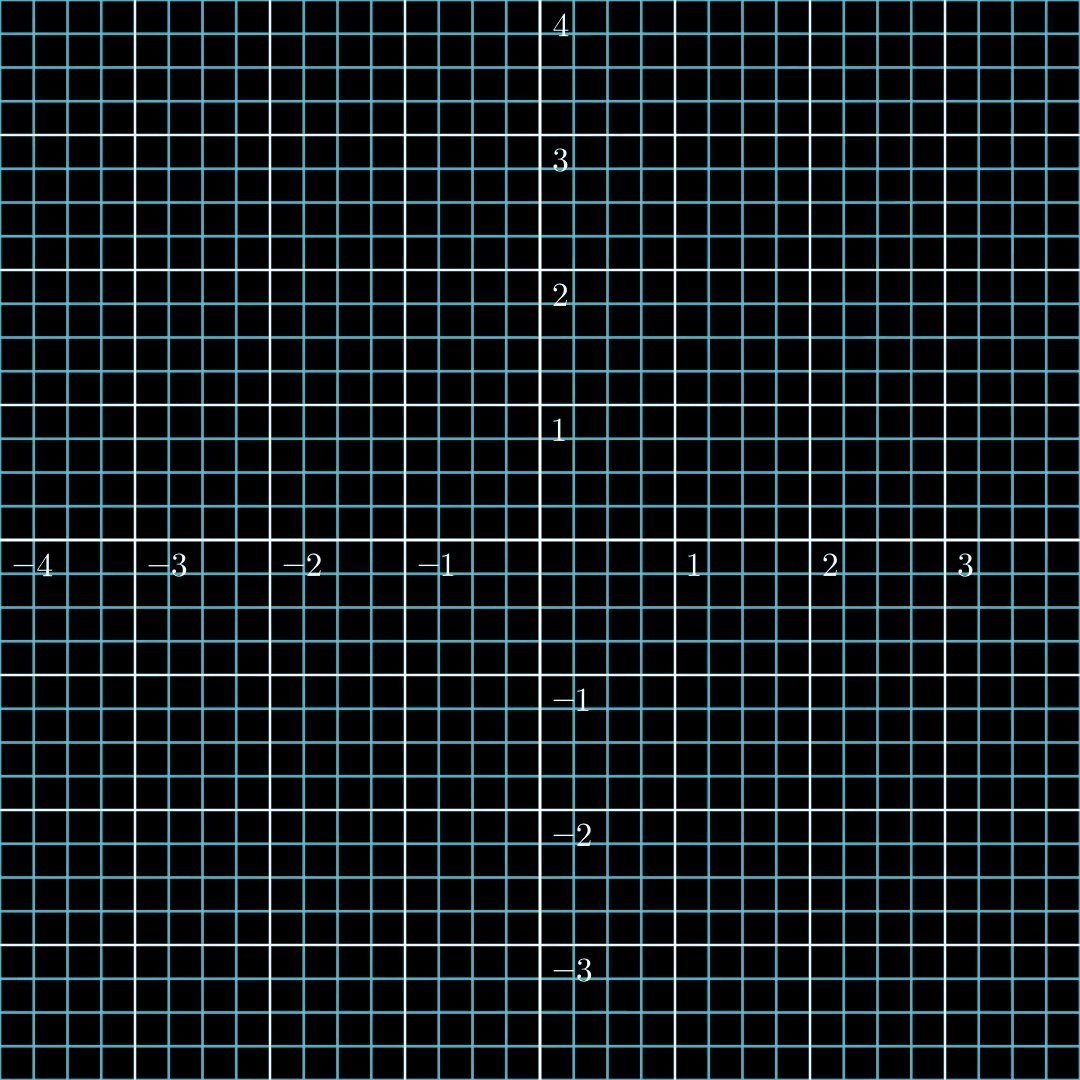

Figure 2: An injective function. Distinct inputs stay distinct, but an output region is not reached.

Figure 2: An injective function. Distinct inputs stay distinct, but an output region is not reached.

Injective Functions

A function is injective (or "one-to-one") if different inputs always produce different outputs. Formally, for any two distinct elements $x_1, x_2$ in $\mathcal{X}$, their outputs $f(x_1)$ and $f(x_2)$ must also be distinct.

For LLMs, injectivity would imply that it's theoretically possible to determine the original input from the model's output, raising significant privacy concerns.

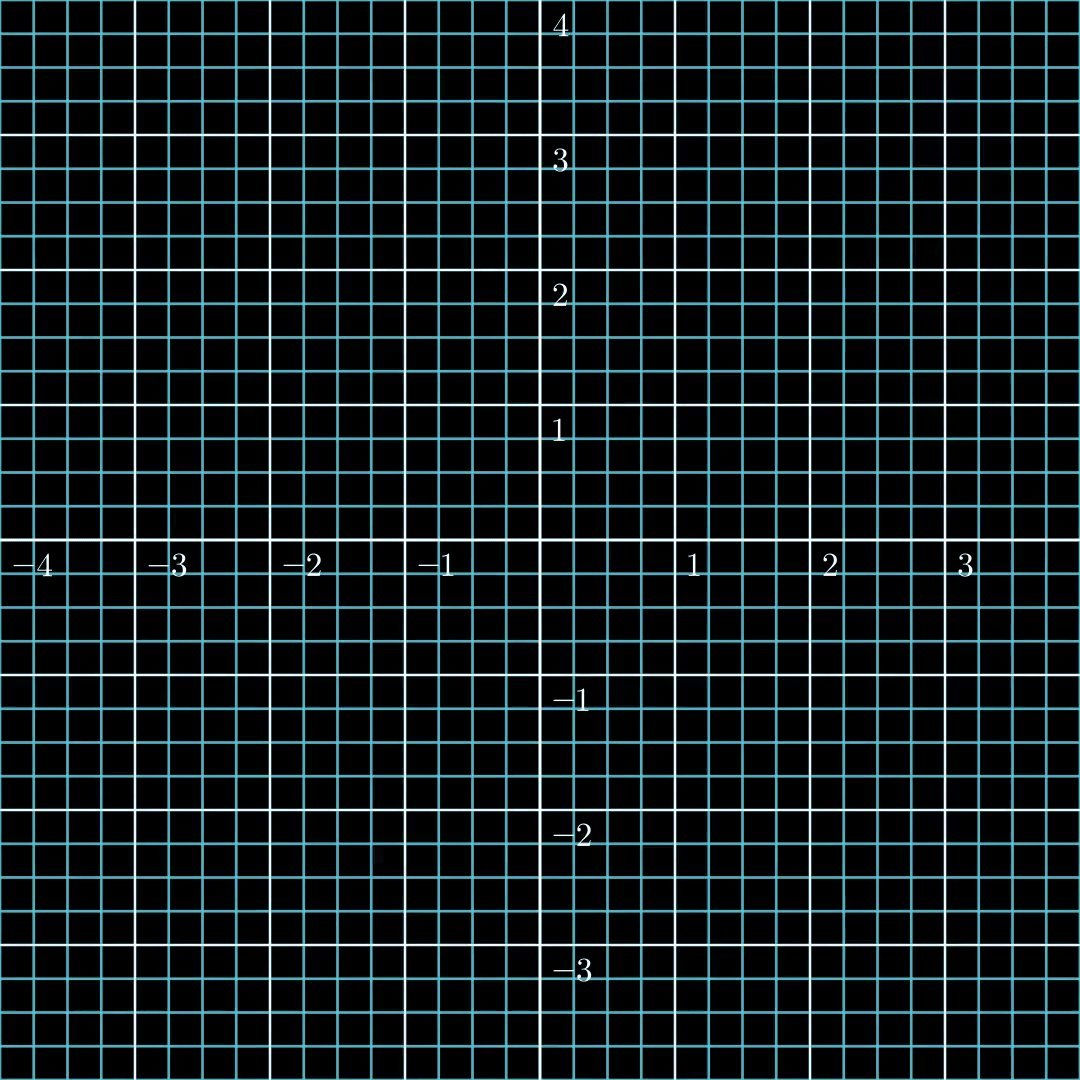

Figure 3: A bijective function. Every vector in the output space has a corresponding unique input.

Figure 3: A bijective function. Every vector in the output space has a corresponding unique input.

Invertible (Bijective) Functions

A function is invertible (or bijective) if it is both surjective and injective. This creates a perfect one-to-one correspondence between inputs and outputs, allowing us to uniquely reverse the mapping from output back to input.

If LLMs were bijective, it would mean they could generate any possible output (surjective) while also allowing perfect reconstruction of inputs from outputs (injective)—a combination with profound implications.

Implications for Large Language Models

When we treat a generative model as a function $f$ where $x$ is the input prompt and $y$ is the generated content, these mathematical properties take on real-world significance.

The Safety Implications of Surjectivity

If an LLM were truly surjective, it would mean jailbreaks are unavoidable in principle. For any harmful output, there would exist some input prompt that could elicit that response from the model.

However, it's crucial to understand that this doesn't automatically make a model unsafe. A generative model that can be jailbroken isn't necessarily surjective—it might only be able to produce a subset of possible harmful outputs, not all conceivable outputs.

Consider the identity function $f(x) = x$. This is clearly surjective but not inherently harmful. In the LLM world, we could approximate this by instructing the model to "repeat the following sentences:"—demonstrating that surjectivity alone doesn't guarantee dangerous behavior.

The real concern emerges when we consider LLMs with physical consequences. In robotics applications, for example, where $\mathcal{X}$ might represent visual inputs and $\mathcal{Y}$ robot actions, a surjective policy would mean there exists some visual input that could cause the robot to perform harmful actions.

The Privacy Implications of Injectivity

If an LLM were injective, it would mean that different input prompts always produce different outputs. This has significant privacy implications because it suggests that, in principle, private information contained in inputs could be recovered from the outputs.

An alternative interpretation of injectivity is that the model functions as a form of lossless compression of the input—preserving all information from the original prompt in the output.

However, just as with surjectivity, injectivity alone doesn't tell us how difficult it would be to actually recover the original input from the output. The theoretical possibility doesn't guarantee practical vulnerability.

A Critical Distinction: Safety vs. Privacy

There's an important asymmetry between how these properties relate to real-world risks:

Safety violations occur when a harmful output can be produced. This connects directly to surjectivity: if the model is surjective onto the set of harmful outputs, then by definition, every harmful output can be generated. The existence of this property itself signals potential danger.

Privacy violations happen when private information can be recovered from the output. Injectivity only tells us that each output corresponds to a unique input, but it doesn't guarantee that this input can be feasibly reconstructed. The information may remain secure even if the mapping is injective, as long as inversion is computationally difficult.

In short, surjectivity points to an immediate safety concern, whereas injectivity's implications depend on whether the inversion is actually achievable in practice.

What Do the Research Papers Actually Claim?

Now let's examine the specific claims made in the two papers that sparked this discussion.

"On Surjectivity of Neural Networks" [1]

This paper proves that the Transformer function ($\text{TF}$) is surjective regardless of its parameters. However, this doesn't necessarily mean LLMs are surjective for two key reasons:

- The paper works in continuous space, while language models operate in discrete space (token sequences).

- The paper doesn't account for autoregressive generation, which is how most modern LLMs produce outputs.

These limitations are significant, but the paper's findings still raise concerns for other generative model architectures like diffusion models and robotics policies, where discretization and autoregression aren't factors.

Figure 4: Contrast between continuous and discrete mappings. The continuous function is surjective, while the discrete function is injective.

Figure 4: Contrast between continuous and discrete mappings. The continuous function is surjective, while the discrete function is injective.

"Language Models are Injective and Hence Invertible" [2]

This paper examines a different function than the first—it proves that the mapping from input token sequences to output embeddings is injective (excluding a negligible subset of the parameter space).

However, this doesn't prove that LLMs are injective from input sequences to output sequences, as different embeddings can still produce the same token when decoded.

Moreover, this function isn't surjective because the set of input sequences is discrete while the set of output embeddings is continuous—no function with discrete inputs can be surjective onto a continuous output space.

The paper's title uses "invertible" in a non-standard way, simply meaning it's possible to invert an already generated output back to its input—not that the function is mathematically bijective.

Figure 5: Discrete to continuous mapping. Different embeddings do not collide.

Figure 5: Discrete to continuous mapping. Different embeddings do not collide.

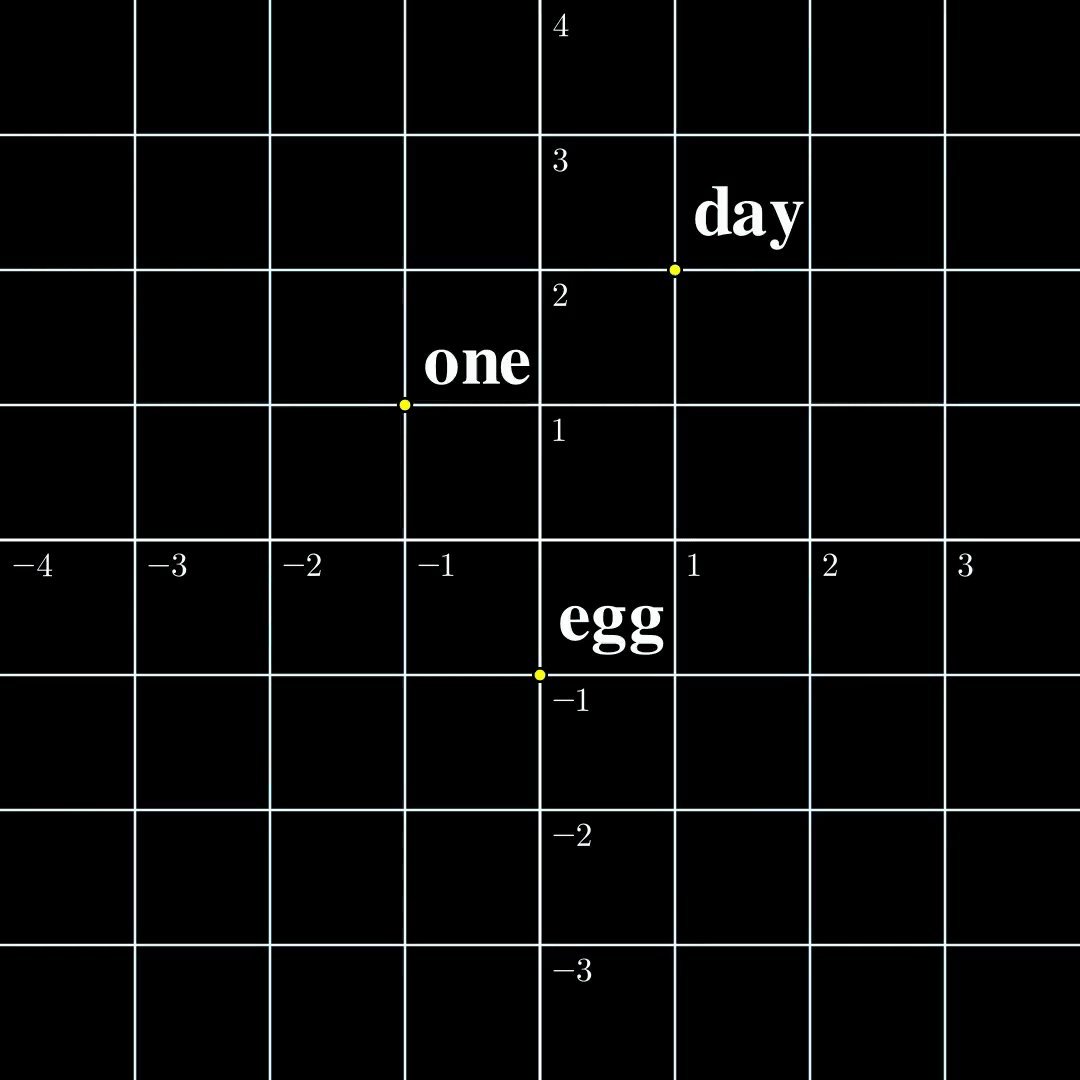

Clarifying the Confusion

To understand why these seemingly contradictory claims coexist, consider a minimal example where the input is a single token from a vocabulary $\mathcal{V} = {\text{one}, \text{day}, \text{egg}}$. This token is transformed into a continuous embedding, which is then processed by the Transformer.

According to the first paper, the mapping from continuous embeddings to continuous outputs is surjective. According to the second paper, the mapping from discrete tokens to continuous embeddings is injective.

These properties aren't contradictory because they describe different functions:

- One maps continuous spaces to continuous spaces

- One maps discrete spaces to continuous spaces

The Reality Check: LLMs Are Neither

After careful analysis, it's clear that LLMs are neither surjective nor injective when considering the mapping from input sequences to output sequences.

While surjectivity has safety implications and injectivity has privacy implications, these threats haven't yet materialized in practical LLM applications. The seemingly conflicting claims from the two papers stem from their different mathematical perspectives and the specific functions they analyze.

More broadly, these properties could indeed imply safety or privacy risks in domains where continuous inputs and outputs are present, such as in robotics or certain types of generative art models.

As the field of AI continues to evolve, understanding these fundamental mathematical properties will become increasingly important for developing safer, more transparent, and more responsible AI systems.

Comments

Please log in or register to join the discussion