The WebAssembly tool-conventions repository defines a Basic C ABI that standardizes how Clang and Rust compile C programs to WASM, enabling seamless interoperability across tools. This ABI cleverly separates the abstract value stack from a managed linear memory stack, handling scalars directly while passing larger aggregates via explicit memory allocation. Developers targeting WASM will find these mechanics essential for understanding generated code and optimizing FFI boundaries.

Unpacking the WebAssembly Basic C ABI: How Compilers Bridge C Code to WASM

WebAssembly (WASM) has evolved from a browser sandbox into a portable binary format powering edge computing, serverless runtimes, and cross-platform applications. Central to this ecosystem is the tool-conventions repository, which outlines standards for tool interoperability. Among its gems is the Basic C ABI, a convention dictating how C programs map to WASM—a spec followed by Clang's wasm32 target and increasingly by Rust for extern "C" functions.

This ABI demystifies WASM's stack management, distinguishing the ephemeral value stack (an abstract operand stack for computations) from the linear stack (a concrete region in WASM's linear memory, managed via the global $__stack_pointer). Understanding these mechanics is crucial for developers porting C libraries to WASM, debugging compiler output, or building WASM runtimes. Eli Bendersky's detailed notes, complete with annotated WASM snippets and diagrams, illuminate the process.

Value Stack vs. Linear Stack: The Foundation

WASM's value stack operates abstractly—no addresses, just push/pop operations. "TOS" denotes the top-of-stack, with notation like [x y] indicating y atop x. Linear memory, however, hosts the ABI's stack, growing downward from high to low addresses (akin to x86), with $__stack_pointer marking the current frame's base. This explicit management mirrors hardware ABIs but uses a global instead of a dedicated register.

Offsets in WASM's load/store instructions enable efficient access relative to $__stack_pointer, avoiding extra adds for stack-relative addressing.

Scalar Parameters and Returns: Direct and Efficient

For basic types like int, double, or char, the value stack suffices. WASM functions accept arbitrary scalar parameters, making simple cases straightforward.

Consider this C function:

int add_three(int x, int y, int z) {

return x + y + z;

}

Clang emits:

(func $add_three (param i32 i32 i32) (result i32)

local.get 1 ;; [ y ]

local.get 0 ;; [ y x ]

i32.add ;; [ x+y ]

local.get 2 ;; [ x+y z ]

i32.add ;; [ x+y+z ])

Smaller integrals pass as i32, sign/zero-extended as needed. For char:

(func $add_three_chars (param i32 i32 i32) (result i32)

;; ... adds ...

i32.extend8_s) ;; Sign-extend low 8 bits

Callers apply matching extensions, ensuring bit-accurate semantics.

Pointers: Scalars with Memory Semantics

Pointers are i32 scalars, but compilers emit loads/stores accordingly:

int add_indirect(int x, int* sum, int y) {

*sum = x + y;

return *sum;

}

(func $add_indirect (param i32 i32 i32) (result i32)

local.get 2 ;; [ ptr_sum ]

local.get 1 ;; [ ptr_sum y ]

local.get 0 ;; [ ptr_sum y x ]

i32.add ;; [ ptr_sum x+y ]

local.tee 0 ;; Reuse param 0

i32.store ;; *ptr_sum = x+y

local.get 0) ;; Return

WASM blurs numbers and addresses—both are i32—but i32.store expects [addr value].

Aggregates via Linear Memory: Stack Frames in Action

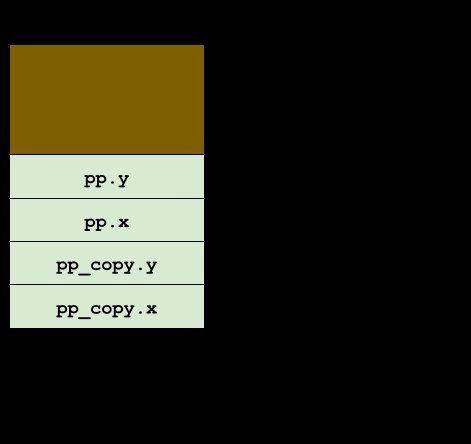

Scalars and single-element structs pass directly, but larger aggregates use the linear stack. Each function allocates a frame by decrementing $__stack_pointer, passes its address, and restores on exit.

For:

struct Pair {

unsigned x, y;

};

unsigned pair_calculate(struct Pair pair);

unsigned do_work(unsigned x, unsigned y) {

struct Pair pp = {.x = x, .y = y};

return pair_calculate(pp);

}

do_work allocates 16 bytes (ABI-mandated alignment), stores pp, and passes its address:

(func $do_work (param i32 i32) (result i32)

(local $sp i32)

global.get $__stack_pointer

i32.const 16

i32.sub

local.tee 2

global.set $__stack_pointer

local.get 2

local.get 1

i32.store offset=12 ;; mem[sp+12] = y

local.get 2

local.get 0

i32.store offset=8 ;; mem[sp+8] = x

;; Pack pair as i64 at sp+0

local.get 2

i64.load offset=8 align=4

i64.store

local.get 2

call $pair_calculate

;; Epilogue: restore stack, return

local.get 2

i32.const 16

i32.add

global.set $__stack_pointer

;; ...)

pair_calculate receives Pair*:

(func $pair_calculate (param i32) (result i32)

local.get 0

i32.load offset=4 ;; pair.y

i32.const 3

i32.mul

local.get 0

i32.load ;; pair.x * 7

i32.const 7

i32.mul

i32.add)

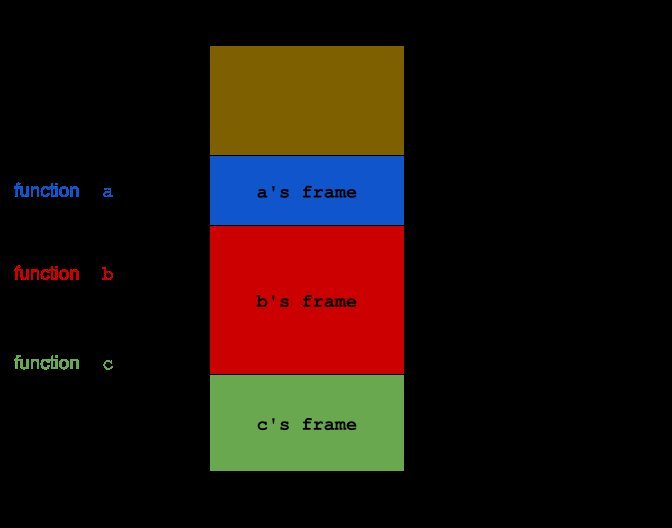

Prologues/epilogues ensure nesting works seamlessly.

Function c restores to b's frame bottom, b to a's—recursive safety without frame pointers for static allocation.

Returning Aggregates: Hidden Pointer Parameter

Returns follow suit: a hidden first parameter (i32 address) precedes user params; the callee writes there.

struct Pair make_pair(unsigned x, unsigned y) {

return (struct Pair){.x = x, .y = y};

}

Becomes:

(func $make_pair (param i32 i32 i32) ;; ret_addr, x, y

local.get 0

local.get 2

i32.store offset=4

local.get 0

local.get 1

i32.store) ;; No result

Callers allocate space in their frame. Note 16-byte alignment—even if 8 bytes suffice.

Advanced Mechanics and Developer Implications

The ABI hints at optimizations like a 128-byte "red zone" for leaf functions (shadow stack below $__stack_pointer) and globals for frame/base pointers (VLAs, >16-byte alignment). These enable C's full expressiveness in WASM.

For developers, this ABI standardizes C-to-WASM compilation, easing Rust FFI, library ports (e.g., via Emscripten/WASI), and toolchains. It exposes WASM's strengths—portability, safety—while retaining C's performance. As WASM runtimes proliferate (Wasmtime, WasmEdge), mastering these conventions unlocks efficient, interoperable modules. Bendersky's visuals and snippets reveal why WASM feels native yet abstract, bridging legacy codebases to tomorrow's compute fabric.

Source: Eli Bendersky's notes on the WASM Basic C ABI (eli.thegreenplace.net/2025/notes-on-the-wasm-basic-c-abi/).

Comments

Please log in or register to join the discussion