Twenty years after its release, Max Payne's graphical innovations reveal how developers overcame severe hardware constraints through perceptual trickery and clever optimization.

Two decades have passed since Max Payne reshaped action gaming with its noir storytelling and bullet-time mechanics. Beyond its cinematic influences, the game's technical achievements in rendering remain worthy of examination. Released in 2001 targeting PCs with 450MHz CPUs and 16MB GPUs—hardware three orders of magnitude weaker than today's machines—the game achieved startling realism through what developers candidly called "smoke and mirrors."

The Illusionist's Toolkit

Particle Systems: Max Payne's particle effects remain its most striking achievement. Bullet impacts generated:

- Crack decals

- White smoke puffs

- "Chip" particles using flipbook animations

- Simulated fluid effects via textured quads

These elements combined to create visceral destruction sequences. A monitor explosion, for example, layered fireball quads with color animations, dynamic vertex lighting, and electrical spark effects—all without actual physics simulation. While particles sometimes clipped through geometry and lacked environmental interaction, their coordinated choreography sold the illusion.

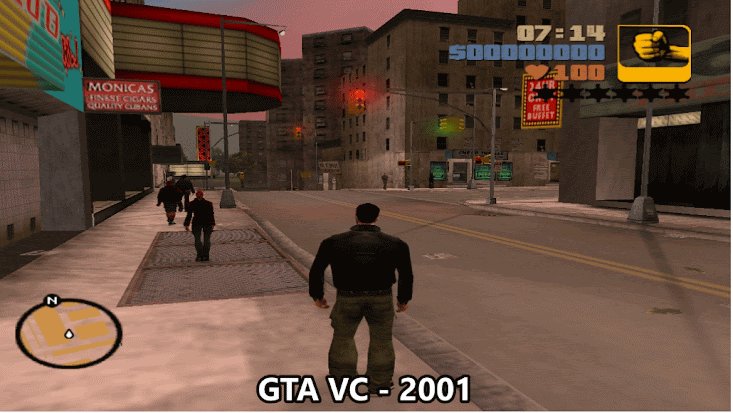

Lighting Constraints: With no dynamic shadows or modern ambient occlusion, developers relied entirely on prebaked lightmaps. This caused visible artifacts:

- Soft shadows with light bleeding

- Absence of contact shadows

- Low-resolution striations (visible in neon signage)

Emissive surfaces like monitors cleverly embedded glow into lightmaps, but dynamic objects (like weapons) appeared disconnected from environments without shadow support.

Texture Trickery: Two techniques overcame polycount limitations:

- Detail Textures: Mono-channel overlays added micro-surface detail

- Baked Geometry: Complex objects like candlesticks were flattened into single polygons with alpha-masked textures

This approach created convincing depth from fixed perspectives but broke down at oblique angles. The infamous "floating toilet" exemplified the tradeoffs.

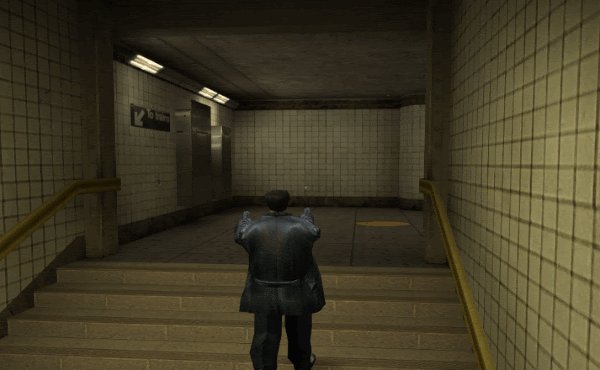

Specular Fakery: Without environment maps or normal mapping, reflections were painted directly onto surfaces. Highlights on subway seats or metal fixtures were pre-rendered approximations that ignored view-dependency—a compromise that worked best in controlled lighting scenarios.

Clever Contextual Tricks

The game supplemented core systems with contextual illusions:

- Footprint decals triggered during walk animations

- Ambient occlusion blobs under characters

- Planar reflections via geometry duplication beneath transparent floors

- Destructible props hand-scripted for specific scenes

These micro-illusions added dynamism within strict constraints. The mirrored floor in the Roscoe Street Station remains particularly impressive, though the technique wasn't applied to NPCs or mirrors elsewhere.

Legacy of Constrained Creativity

Max Payne's graphics weren't flawless—inconsistent detail textures, primitive decals, and visible clipping remind us of its era. Yet its triumphs outweigh these quibbles. By coordinating particle choreography, baked lighting, and perceptual shortcuts, developers achieved a cohesive aesthetic that outpaced contemporaries. Games wouldn't match this density of environmental storytelling for several years.

The title stands as a case study in doing more with less. Modern developers might consider its approach when optimizing for mobile or VR platforms. As Remedy Entertainment's official page notes, the game's fusion of tech and artistry became their signature. For deeper technical study, Valve's alpha-tested magnification paper explores similar texture techniques, while modern implementations appear in LearnOpenGL's cubemaps tutorial.

Ultimately, Max Payne demonstrated that graphical immersion stems not from raw power, but from understanding human perception—a lesson that resonates 20 years later.

Comments

Please log in or register to join the discussion