An exploration of k-way merge algorithms reveals how databases efficiently combine sorted data runs, with interactive visualizations demonstrating four distinct approaches and their trade-offs.

The challenge of sorting massive datasets that exceed memory capacity has persisted since the era of tape drives, yet remains critically relevant in modern database systems. At the heart of this challenge lies the k-way merge algorithm—a sophisticated technique for combining multiple sorted sequences into a single ordered output. This fundamental operation powers everything from LSM-tree compaction to query execution in today's most advanced databases.

The Persistent Need for External Sorting

Databases face a fundamental constraint: data volumes often dwarf available memory. This necessitates external sorting techniques where data is processed in chunks. The 1960 U.S. Census exemplifies early adoption, where UNIVAC 1105 systems with limited memory sorted records using balanced k-way merges across tape drives. The core principle remains unchanged—read sorted runs, merge them efficiently, write consolidated output—though modern implementations have evolved significantly.

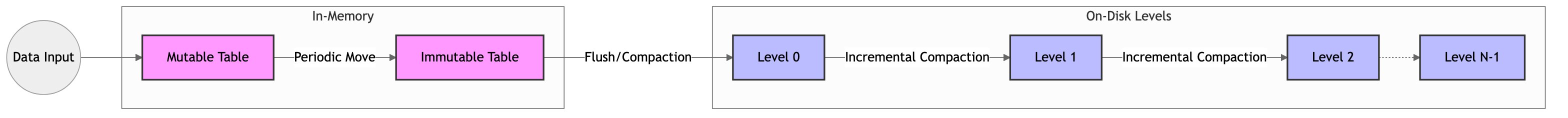

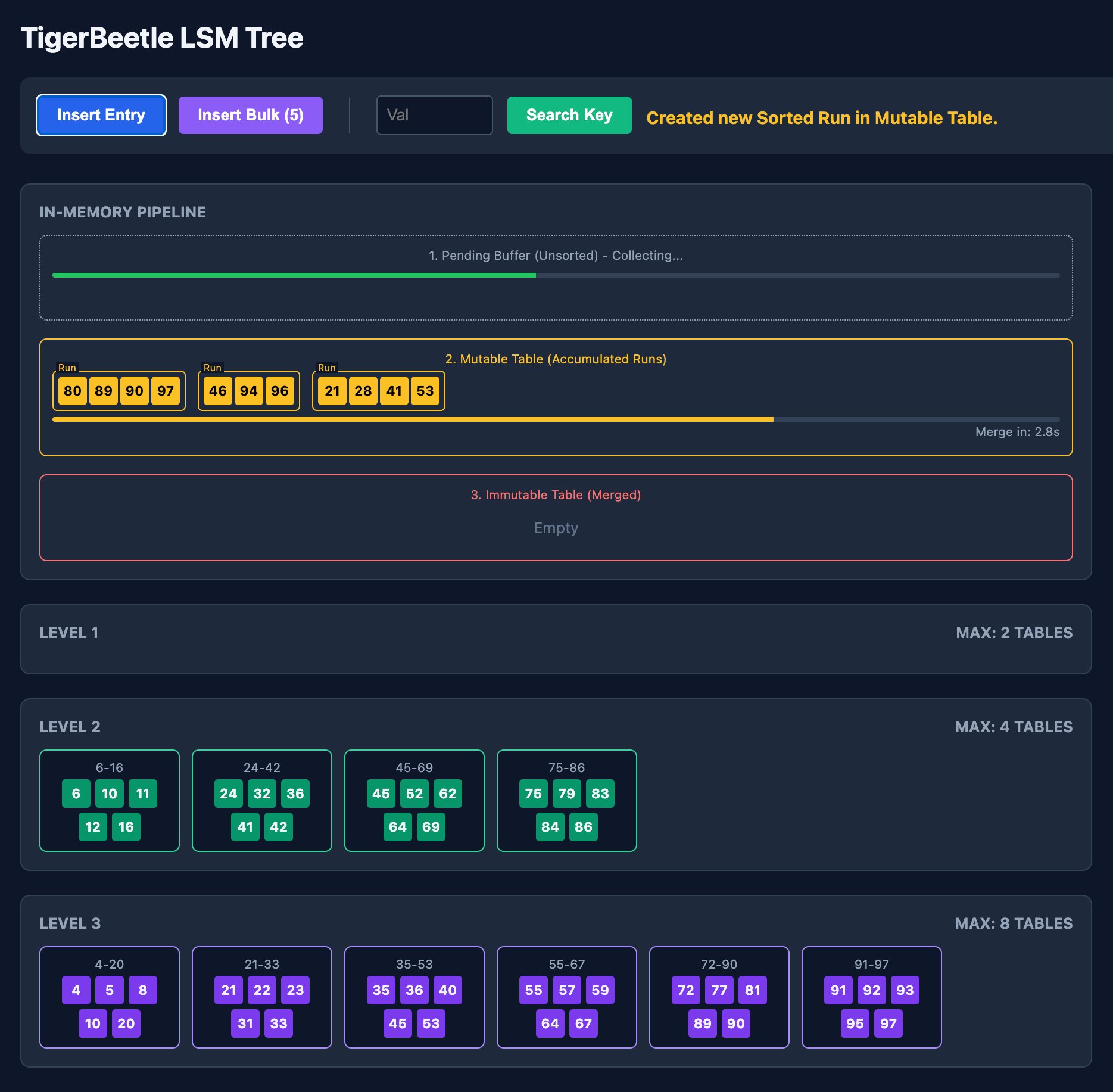

LSM Trees: Modern Sorting Workhorses

Log-Structured Merge-Trees (LSM-Trees) exemplify contemporary applications. Systems like RocksDB, Cassandra, and TigerBeetle buffer writes in memory before flushing sorted runs (SSTables) to disk. Periodic compaction merges these runs using k-way algorithms. As TigerBeetle engineer Justin Heyes-Jones explains: "The mutable table actually consists of 32 sorted runs merged before flushing to disk."

Four Paths to Efficient Merging

K-way merge implementations reveal fascinating engineering trade-offs:

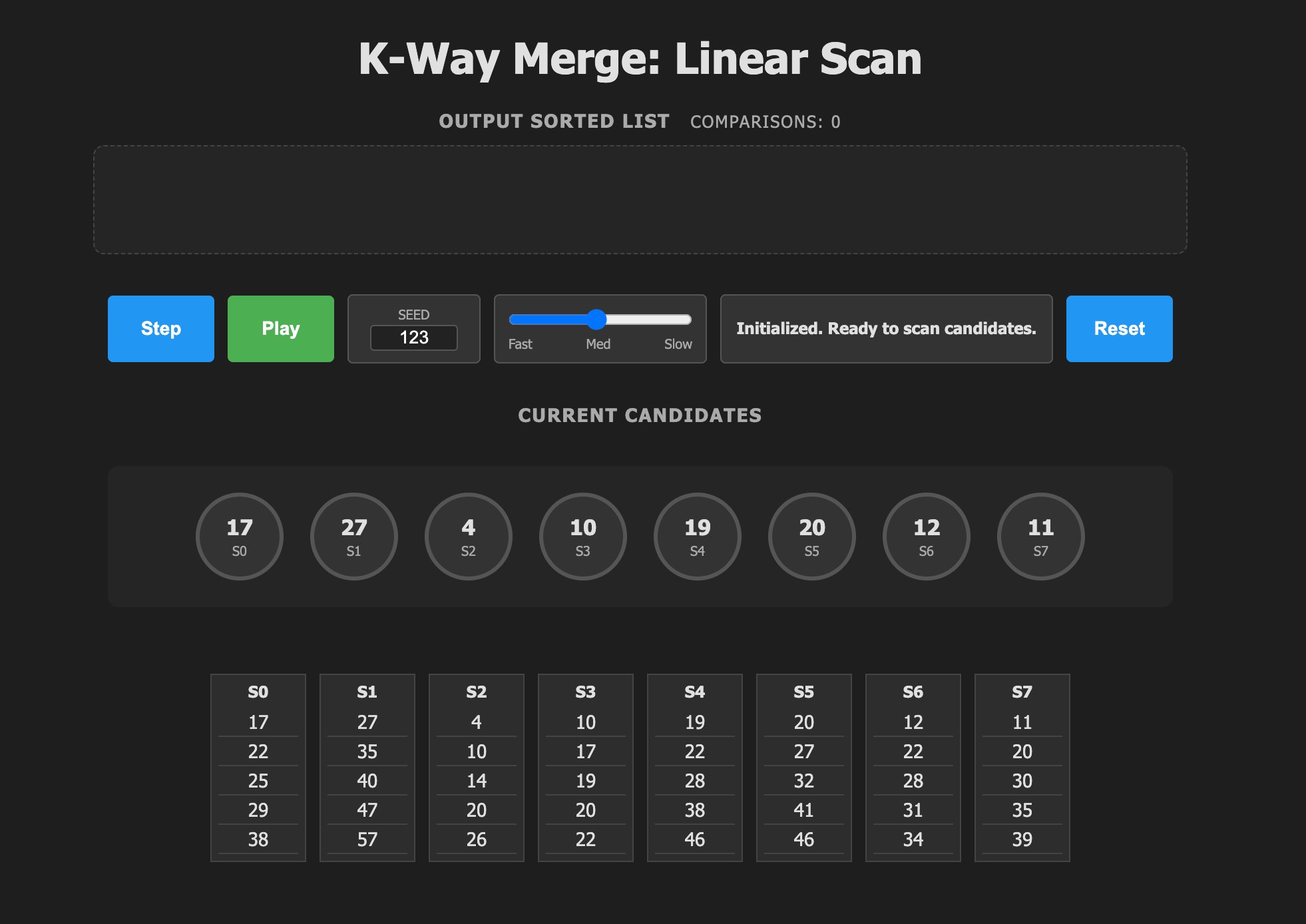

- Linear Scan

The simplest approach compares all k candidates per output element. While O(kn) complexity seems inefficient, its simplicity shines for small k values. Modern CPUs can accelerate this with SIMD instructions (AVX2/AVX-512) for k≤16.

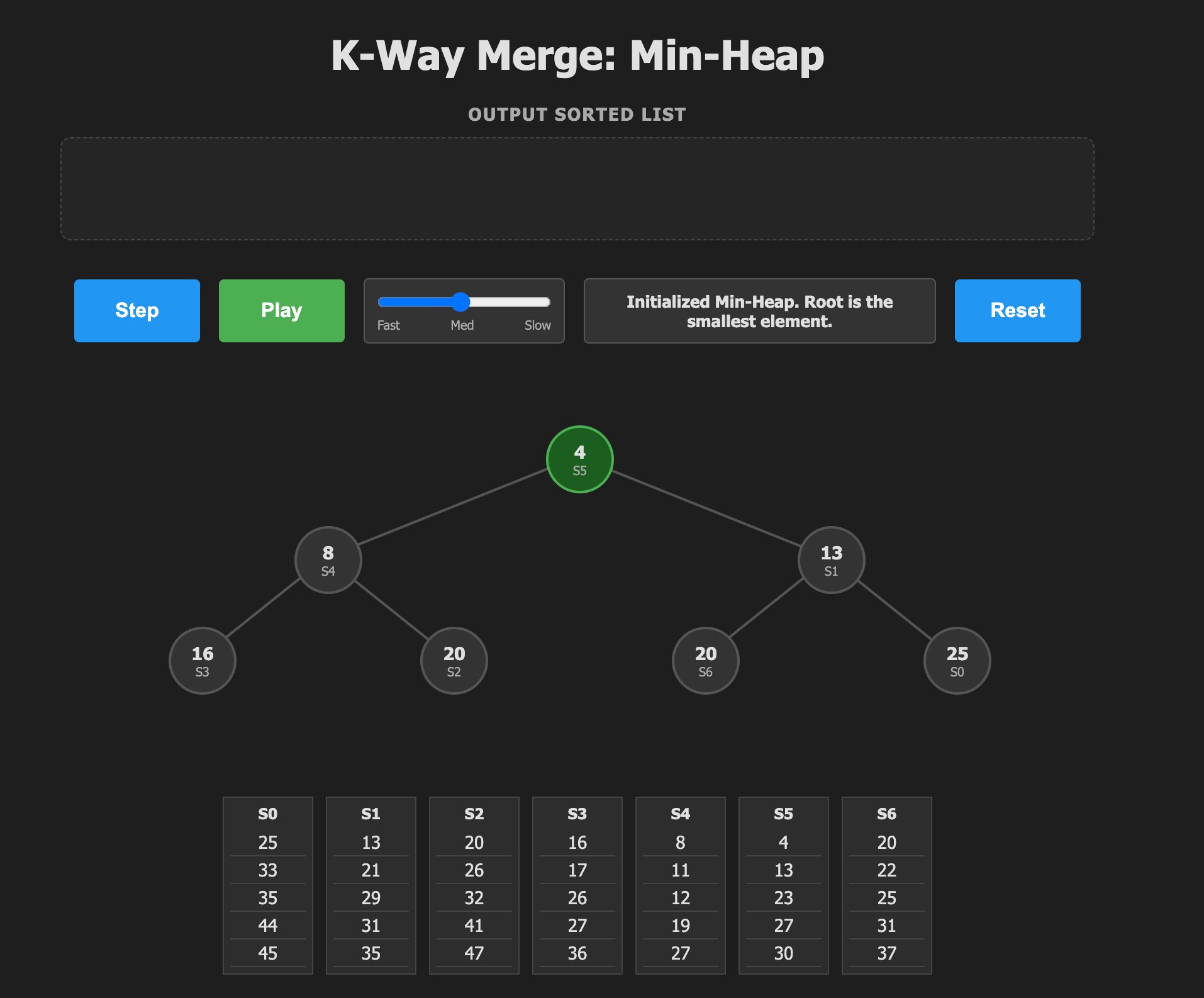

Min-Heap

Widely used in databases like ClickHouse, this approach maintains a binary heap of candidates. Each pop-insert cycle costs O(log k), yielding O(n log k) complexity. The Eytzinger memory layout optimizes cache locality, but requires two comparisons per level during sift-down operations.Tree of Winners

Inspired by tournament structures, this method propagates winners up a tree. After removing the champion, it replays only affected matches. Though asymptotically identical to heaps (O(n log k)), it reduces comparisons by half and offers predictable memory access patterns.

- Tree of Losers

H.B. Demuth's 1956 innovation stores losers at each node while tracking the winner separately. This approach minimizes memory fetches by keeping the current winner in registers and comparing only against stored losers during replays. The fixed traversal path optimizes branch prediction.

Algorithmic Tradeoffs in Practice

| Algorithm | Comparisons | Key Advantage | Optimal Use Case |

|---|---|---|---|

| Linear Scan | O(k) | SIMD acceleration | Small k (≤16) |

| Min-Heap | 2 log k | Standard libraries | Moderate k |

| Tree of Winners | log k | Fewer comparisons | Larger k, predictable access |

| Tree of Losers | log k | Register optimization | Performance-critical systems |

As TigerBeetle's implementation demonstrates, the choice depends on specific constraints. For merging ≤16 runs, linear scans with SIMD often outperform complex structures. Beyond that threshold, loser trees provide superior throughput by minimizing pipeline stalls and memory access latency.

Implications for Database Design

These algorithms transcend theoretical interest—they directly impact system performance. Columnar databases like DuckDB leverage vectorized merges during partition consolidation, while search engines like Apache Lucene depend on heap-based segment merging. The ongoing evolution of storage hardware further complicates these decisions: NVMe's low-latency access favors different optimizations than spinning disks required.

Counterintuitively, simpler approaches sometimes prevail. As Heyes-Jones notes: "For small values of k, linear scan may be faster despite worse asymptotic complexity." This pragmatism reflects database engineering's nuanced reality, where theoretical bounds must be balanced with hardware characteristics and workload patterns.

Explore TigerBeetle's actual implementation to see these principles applied. As data volumes continue growing, the elegant mathematics of k-way merging will remain essential to extracting order from chaos.

Comments

Please log in or register to join the discussion