Four decades after Steve Jobs introduced the original Macintosh, the Windows, Icons, Menus, and Pointer (WIMP) computing model remains the foundational interface for personal and professional computing, despite decades of alternative interface research.

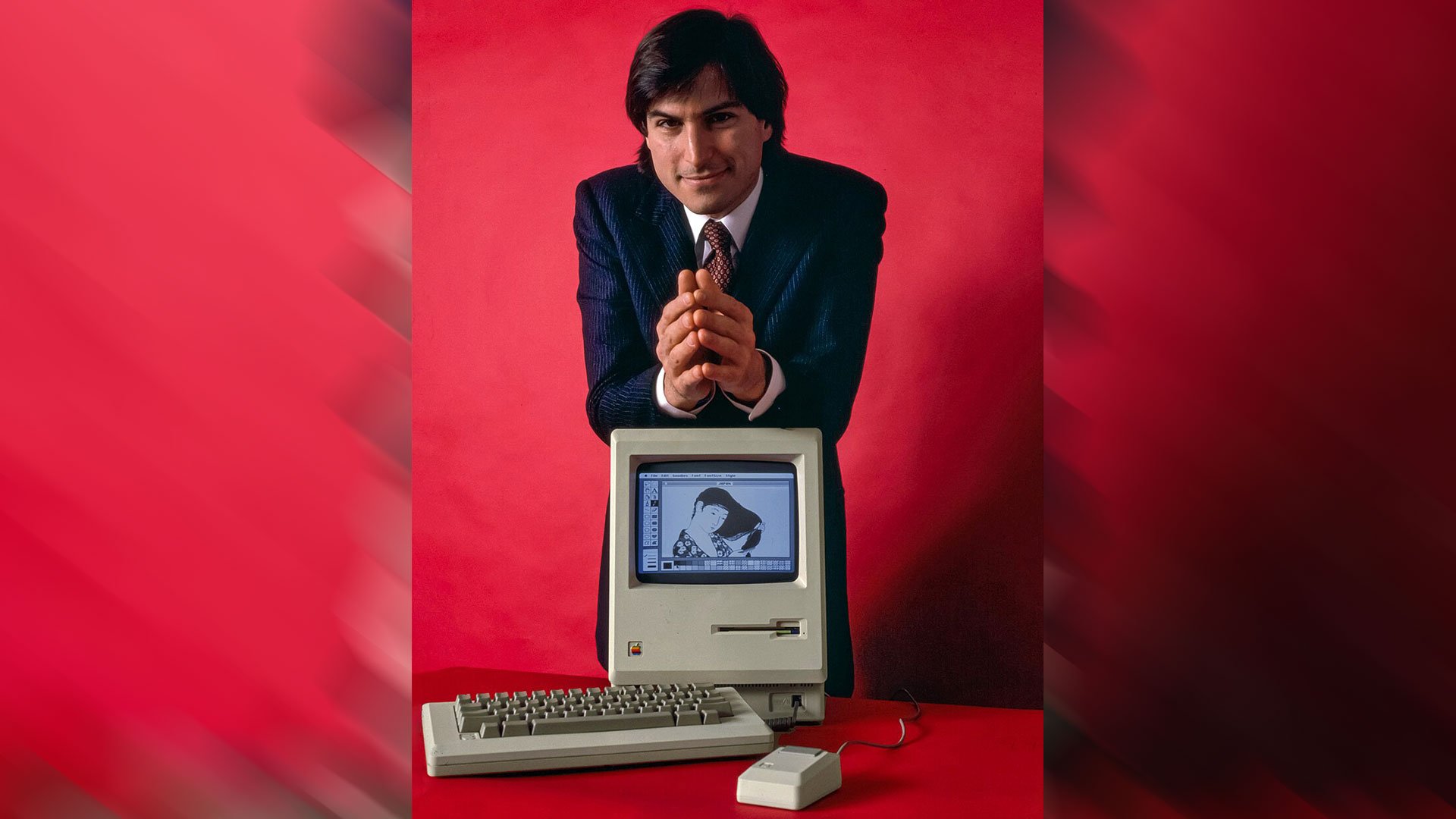

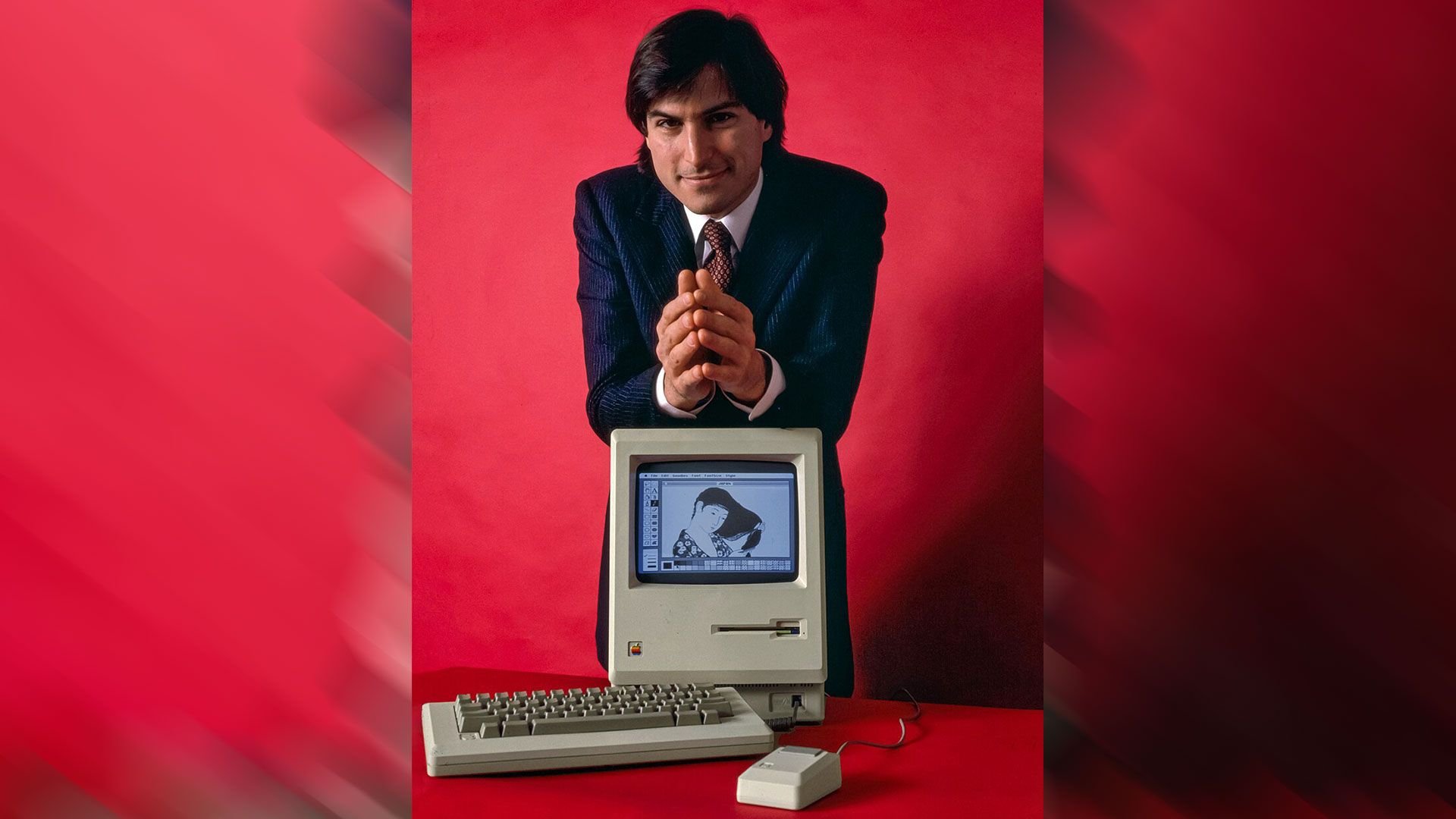

When Steve Jobs unveiled the original Apple Macintosh on January 24, 1984, he wasn't just launching a new computer—he was cementing a human-computer interaction paradigm that would define computing for the next four decades. The Macintosh 128K, priced at $2,495 (equivalent to over $7,500 in 2026 dollars), introduced millions to the intuitive windows, icons, menus, and pointers (WIMP) model, a system that remains the dominant interface for personal computing in 2026.

The original Macintosh demonstration was a masterclass in product presentation. Jobs began with an unassuming rectangular bag that resembled a modern insulated delivery bag, then produced the sleek, all-in-one computer. After connecting power and mouse, the screen immediately displayed a disk icon, prompting for media. Jobs then inserted a 3.5-inch floppy disk from his blazer pocket, and the computer began its demonstration sequence. The audience witnessed a scrolling "MACINTOSH" banner, followed by a series of GUI-based applications showcasing what-you-see-is-what-you-get (WYSIWYG) painting, desktop publishing, and font rendering—capabilities that would ship with the system and define creative workflows for years.

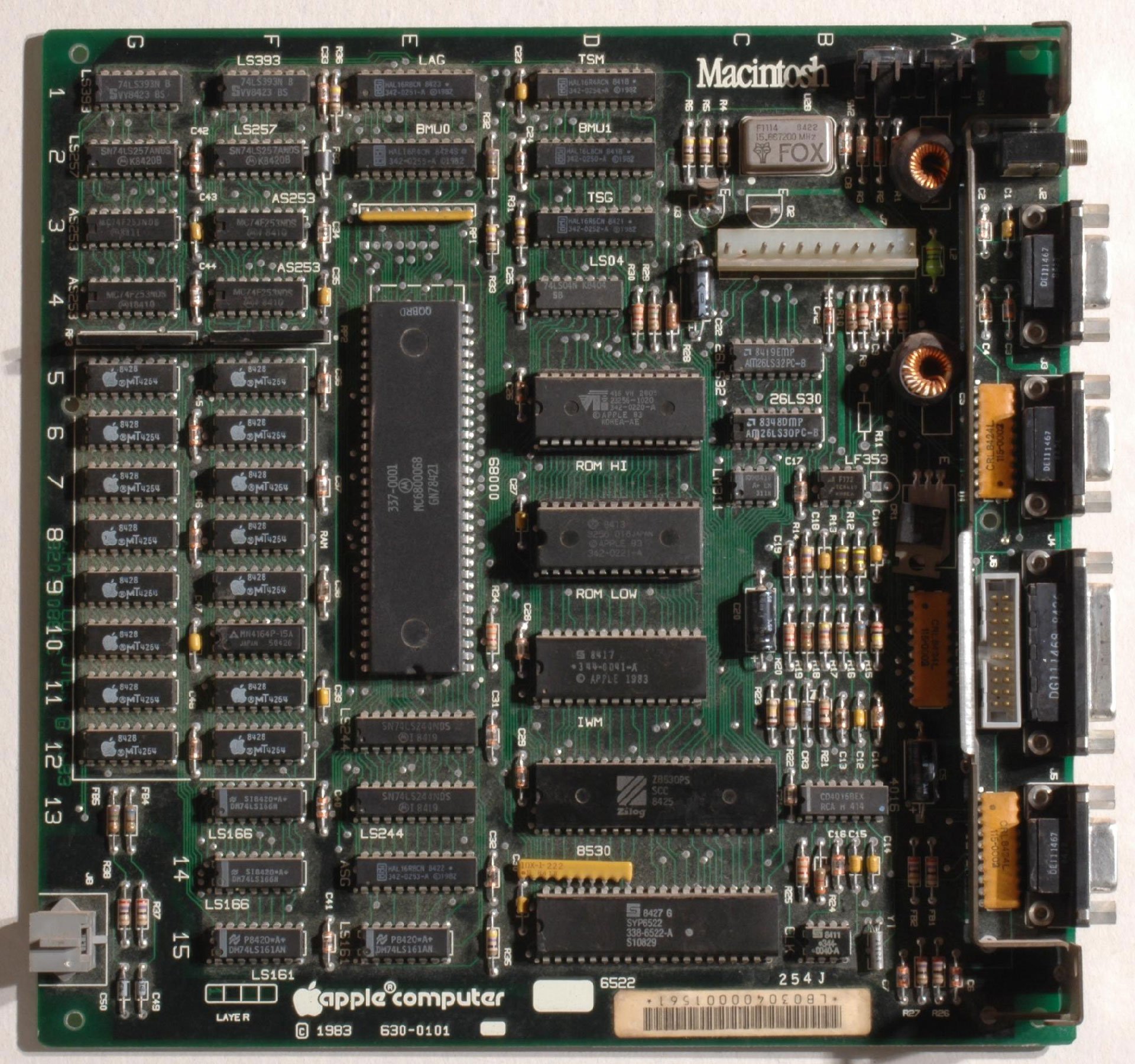

The technical foundation of the original Macintosh was built around the Motorola 68000 processor, running at 8 MHz with 128 KB of RAM. The system featured a 9-inch black-and-white display with a resolution of 512×342 pixels. The computer's architecture included custom chips like the Video Controller (VC) and I/O Controller (IOC), which managed the system's graphics and peripheral interfaces. This hardware-software integration was crucial to the Macintosh's responsive user experience, a stark contrast to the command-line interfaces of the era.

While Apple popularized the WIMP model, the concept wasn't entirely original. The graphical user interface was pioneered at Xerox PARC in the 1970s with the Alto computer, which featured a bitmap display, mouse, and windowing system. Apple's innovation wasn't in inventing the GUI, but in refining it for mass consumption and integrating it into a cohesive, user-friendly package. The Macintosh's success lay in its consistency—every application followed the same interface conventions, making the system approachable for non-technical users.

The competitive landscape quickly evolved. By mid-1985, both Atari and Commodore launched their own Motorola 68000-based systems with graphical interfaces. The Atari ST featured the GEM (Graphics Environment Manager) desktop, while the Commodore Amiga introduced a more advanced multitasking operating system with superior graphics and sound capabilities. These systems shared the same CPU architecture but diverged significantly in their operating system designs and supporting chipsets. The Amiga's custom chipset, including the Paula audio chip and the Copper coprocessor, enabled graphics and audio capabilities that surpassed the Macintosh's initial offering.

Microsoft and IBM entered the GUI arena in November 1985 with Windows 1.0, though this early version was more of a graphical shell for MS-DOS than a true operating system. Windows wouldn't achieve widespread adoption until Windows 3.0 in 1990, and it wouldn't fully compete with the Macintosh's integrated experience until Windows 95 in 1995. The delay in Microsoft's GUI transition highlights the technical and cultural challenges of shifting from command-line to graphical interfaces.

The persistence of the WIMP paradigm in 2026 is remarkable given the extensive research into alternative interfaces. Three-dimensional interfaces, augmented reality (AR), extended reality (XR), virtual reality (VR), voice interaction, gesture controls, and even brain-computer interfaces have all been explored as potential replacements. Each alternative offers specific advantages: VR provides immersive environments for specialized applications, voice interaction enables hands-free operation, and gesture controls can be more intuitive for certain tasks. However, none have achieved the universal applicability and efficiency of the WIMP model for general-purpose computing.

The WIMP model's endurance stems from several fundamental advantages. First, it provides a spatial metaphor that maps well to human cognitive processes—windows represent documents or applications, icons represent objects, menus offer structured choices, and pointers provide precise selection. This metaphor scales from simple tasks to complex workflows. Second, the model is highly efficient for information-dense tasks like document editing, programming, and data analysis, where precise selection and manipulation are required. Third, decades of refinement have optimized the model for both novice and expert users, with keyboard shortcuts and advanced features for power users.

Modern operating systems have evolved the WIMP paradigm rather than replacing it. Windows 11, macOS Sequoia, and Linux desktop environments like GNOME and KDE all build upon the foundational WIMP concepts while adding modern features like virtual desktops, window management enhancements, and touch interface adaptations. The paradigm has proven flexible enough to incorporate new interaction methods—touchscreens, stylus input, and voice commands—without abandoning its core principles.

For those interested in experiencing the original Macintosh interface, resources like the Infinite Mac website provide emulations of classic Macintosh systems, including System 1.0 from the original 128K Mac. These emulations demonstrate how the fundamental WIMP concepts have remained consistent even as hardware capabilities have increased by orders of magnitude.

The semiconductor industry's evolution has been intrinsically tied to the WIMP paradigm's demands. The original Macintosh's 8 MHz Motorola 68000 required significant optimization to deliver responsive graphical interactions. Modern processors, with clock speeds exceeding 5 GHz and multiple cores, can handle complex 3D graphics, high-resolution displays, and multitasking with ease, yet the underlying interaction model remains recognizable. The shift from 8-bit and 16-bit systems to 64-bit architectures, the introduction of dedicated graphics processing units (GPUs), and the move to solid-state storage have all been driven, in part, by the need to make graphical interfaces more fluid and responsive.

Supply chain considerations also played a role in the WIMP paradigm's dominance. The standardized hardware components of the PC ecosystem—Intel or AMD CPUs, NVIDIA or AMD GPUs, standardized motherboards—created a consistent platform for Windows and other GUI operating systems. Apple's vertical integration, controlling both hardware and software, allowed for tighter optimization but at a higher cost. The PC's open architecture enabled rapid innovation and price competition, making GUI computing accessible to a broader market.

Looking forward, the WIMP paradigm faces challenges from mobile computing, where touch interfaces have become dominant, and from specialized applications where 3D or VR interfaces provide clear advantages. However, for productivity tasks, content creation, and general-purpose computing, the WIMP model's efficiency and familiarity ensure its continued relevance. The paradigm has demonstrated remarkable resilience, adapting to new hardware capabilities while maintaining its core principles.

The original Macintosh's 42-year legacy is not just about a specific computer or operating system, but about establishing a human-computer interaction model that has stood the test of time. While future interfaces may emerge for specialized applications, the WIMP paradigm's combination of spatial metaphor, efficiency, and adaptability will likely keep it at the center of personal computing for years to come. The challenge for future interface designers is not to replace the WIMP model entirely, but to extend it in ways that enhance productivity without sacrificing the intuitive clarity that made the original Macintosh revolutionary.

Comments

Please log in or register to join the discussion