In large organizations, common frustrations about slowness, silos, and endless meetings all stem from a single root cause: the fundamental expense of human coordination. This article explores why coordination costs are an organizational law of thermodynamics, how they manifest in everyday work, and why there's no simple tool or reorganization that can eliminate them.

If you’ve ever worked at a larger organization, you’ve likely asked or heard these questions: “Why do we move so slowly? We need to figure out how to move more quickly.” “Why do we work in silos? We need to break out of these.” “Why do we spend so much time in meetings? We need no-meeting days to get real work done.” “Why do we maintain multiple solutions for the same problem? We should standardize on one.” “Why so many management layers? We should remove them and increase span of control.” “Why constant re-orgs? They’re so disruptive.”

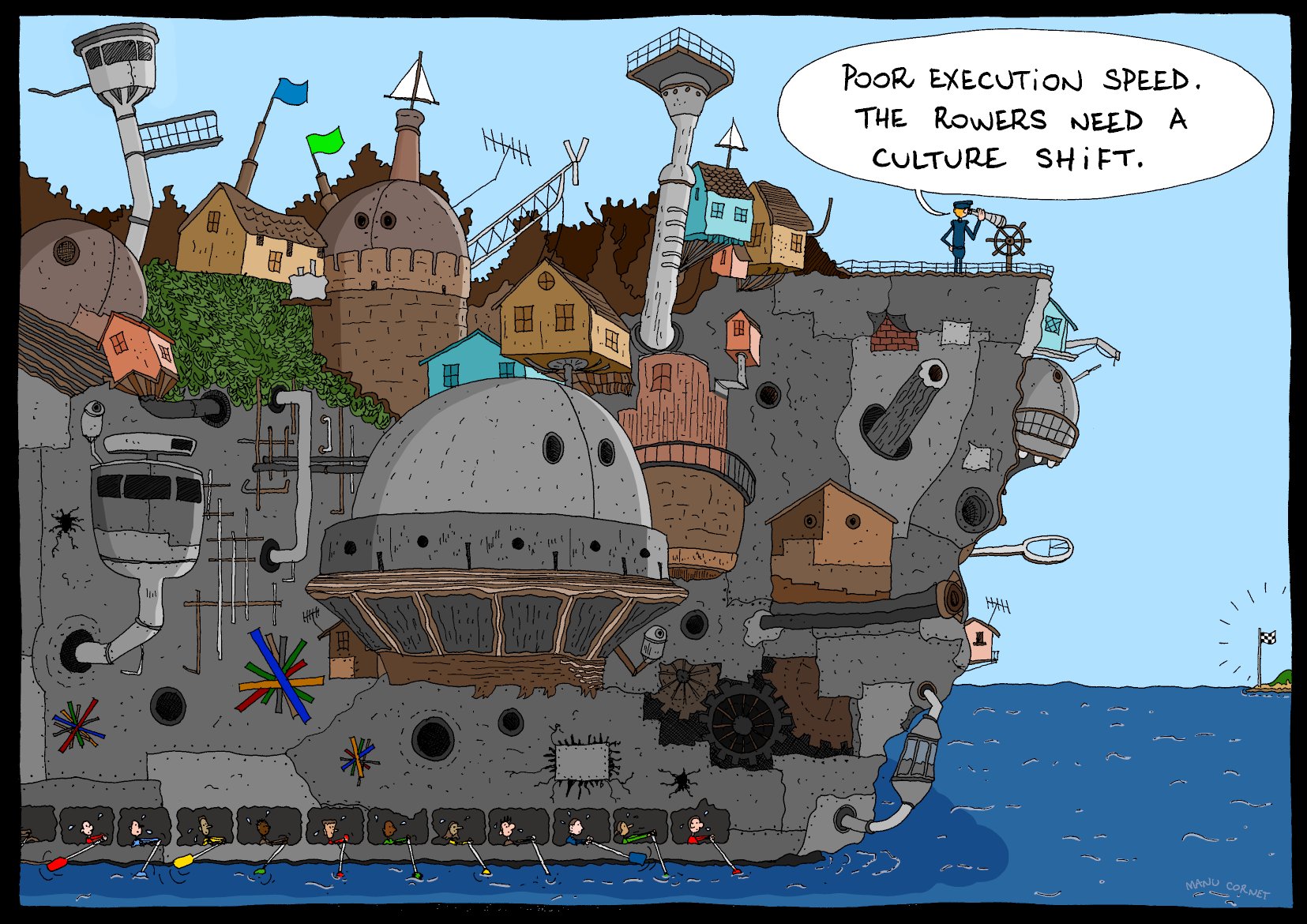

The answer to all of these is the same: because coordination is expensive. It requires significant effort for a group of people to work together to achieve a task too large for any individual. The more people involved, the higher the coordination effort grows—both in difficulty and in time, measured in person-hours. This is why siloed work and duplicated systems persist; it requires less effort to work within an organization than to coordinate across it. The incentive is to do localized work whenever possible to reduce coordination costs.

Time spent in meetings is one aspect of this cost, which people acutely feel because it deprives them of individual work time. But meeting time is still work—it’s unsatisfying-feeling coordination work. When was the last time you discussed your meeting participation in a performance review? Nobody gets promoted for attending meetings, yet humans need them to coordinate work, so they keep happening. As organizations grow, they require more coordination, which means more resources devoted to coordination mechanisms like meetings and middle management. It’s like an organizational law of thermodynamics.

This is why ICs at larger organizations talk so much about Tanya Reilly’s notion of “glue work.” It’s why companies run campaigns like “One SendGrid” to improve coordination. The challenges of coordination create a brisk market for tools: Gantt charts, written specifications, Jira, Slack, daily stand-ups, OKRs, kanban boards, Asana, Linear, pull requests, email, Google Docs, Zoom—the list is endless. Both spoken and written language are the ultimate communication ur-tools. Yet despite all these tools, coordination remains hard.

Remember when Google experimented with eliminating engineering managers in 2002? That lasted only a few months. In 2015, Zappos tried holacracy—flat on paper, hierarchy in practice. These experiments failed because human coordination is fundamentally difficult. There’s no one weird trick that makes the problem go away.

Large companies try different strategies to manage ongoing coordination costs. Amazon is famous for decentralization, operating almost like a federation of independent startups and enforcing coordination through software service interfaces, as described in Steve Yegge’s famous internal Google memo. Google, conversely, invests heavily in centralized tooling for coordination. But some coordination challenges fall outside these solutions, like initiatives involving multiple teams and orgs. I haven’t worked inside Amazon or Google, but employees likely have great stories.

During incidents, coordination becomes acute, and humans are good at acute problems. Organizations explicitly invest in incident manager on-call rotations to manage communication costs. But coordination is also a chronic problem in organizations, and we’re less adept at handling chronic issues. The first step is recognizing the problem: meetings are real work, frequently done poorly, but that argues for improving them, not eliminating them. Similarly, glue work has real value.

The persistence of coordination costs explains why organizations evolve toward more structure, not less. As teams grow, the communication pathways multiply exponentially. A team of five has ten possible pairwise communication channels; a team of twenty has one hundred ninety. This isn’t just a scaling problem—it’s a fundamental constraint of human cognition and social dynamics. We can only maintain so many relationships, and each relationship requires maintenance through meetings, documentation, and alignment sessions.

The tools we adopt—Jira, Slack, Google Docs—don’t reduce coordination costs; they merely shift where the effort goes. A well-written specification saves meeting time but requires upfront writing effort. A Slack channel reduces email volume but creates constant context-switching. The coordination cost is never eliminated, only transformed. This is why organizations keep searching for new tools, hoping the next one will finally solve the problem. It won’t.

The tension between autonomy and alignment is eternal. Too much autonomy leads to silos and duplication; too much alignment creates bureaucracy and slowness. Every reorganization attempts to find a new balance point, but the underlying trade-off remains. The “One Company” campaigns are attempts to push the needle toward alignment, while decentralization efforts push toward autonomy. Both are valid strategies with different coordination costs.

What does this mean for individuals and teams? First, recognize that coordination work is valuable, even if it feels unsatisfying. The engineer who bridges teams, documents decisions, and facilitates meetings is doing critical work. Second, accept that some duplication is inevitable—it’s often cheaper than the coordination required to eliminate it. Third, when choosing tools or processes, consider the coordination cost they impose, not just the features they offer.

For leaders, the lesson is that there’s no perfect structure. The goal isn’t to eliminate coordination costs but to manage them consciously. Invest in the coordination mechanisms that matter most for your context. Sometimes that means more meetings; sometimes it means better documentation. Sometimes it means accepting slower progress to maintain alignment.

The chronic nature of coordination problems means they require ongoing attention, not one-time fixes. Regular retrospectives on how teams work together, not just on what they deliver, can surface coordination pain points. Creating space for “glue work” in career ladders and performance reviews acknowledges its importance.

Ultimately, coordination is expensive because humans are complex, context is rich, and goals are interdependent. No tool or organizational design can change that fundamental reality. The best we can do is acknowledge the cost, distribute it fairly, and continuously refine our approaches. The organizations that thrive aren’t those that eliminate coordination costs, but those that understand and manage them wisely.

This perspective reframes common frustrations. That meeting you hate? It’s probably necessary. That siloed team? They’re likely optimizing for their own coordination costs. That duplicated system? It might be the pragmatic choice. By understanding coordination as an expensive but necessary resource, we can make better decisions about how to invest our organizational energy.

Comments

Please log in or register to join the discussion