In 1968, a Swiss hotel manager named Erich von Däniken published a book that would sell 25 million copies by arguing that human history was shaped by extraterrestrials. An archaeologist breaks down why his arguments are not just wrong, but intellectually bankrupt.

In 1968, an obscure Swiss hotel manager published a book titled Erinnerungen an die Zukunft. The English edition appeared as Chariots of the Gods? The author, Erich von Däniken, claimed that visitors from outer space had shaped human history and improved human potential through cross-breeding. His proof, he said, lay clearly visible in the archaeological record.

The book sold 7 million copies. His total sales, including later books, passed 25 million across 32 countries. Archaeologists looking at these numbers feel a mixture of sadness, fear, and anger. Von Däniken has sold more books about archaeology than any archaeologist who ever lived. His arguments seem self-evidently ridiculous to specialists, yet his version of ancient human history may be the one most widely held by literate people today.

When Playboy asked him when he became convinced his theories were true, von Däniken replied: "I wrote Chariots of the Gods? in 1966, so for me it's an old book. When I wrote it I was not at all convinced. By the second book, Gods from Outer Space, I was more certain, but not absolutely. The basic thing is to be convinced that the fundamental theory is right, that we have been visited from outer space and those visitors altered our intelligence by artificial mutation. Of this I have felt certain for the past four years or so."

If von Däniken can convince even himself, his book sales suggest his version of history has a powerful hold. Archaeologists who attempt to reclaim prehistory from him point out that his argument is built on pathetically flawed logic and non-existent evidence. Yet these shortcomings are conceded and forgiven by his public. He raises so much smoke that many laypersons suspect the fire must be somewhere inside.

The Problem of the Alligators

When grappling with von Däniken's arguments, an old Army saying applies: When you're up to your neck in alligators, it's hard to drain the swamp. Assertion after assertion springs from his pages, confounding any archaeologist who would try to address each item responsibly. If we wrestle his myriad alligators one at a time, we will never be able to fight free long enough to drain the swamp.

Not all of his alligators can be pinned, but some can. Consider his claim that "we find stone giants belonging to the same style" at both Easter Island, 2300 miles west of Chile, and Tiahuanaco in the Bolivian Andes. A simple pair of photographs can discredit this. The Tiahuanaco figures stand on a plain near Lake Titicaca, carved between A.D. 500 and 100. They are 10 feet tall. The Easter Island Maoi often reach 30 feet in height and were carved between A.D. 1100 and 1680. They do not belong to the same style or time period.

Von Däniken claims the Incas cultivated cotton in Peru in 3000 B.C. and calls this a mystery. Any visitor to The University Museum's Peruvian Gallery can see 4500-year-old cotton fishnet fragments from Huaca Prieta. The Incas, moreover, did not appear on the South American scene until the 13th century A.D. or later. The museum displays these artifacts openly.

But how can one disprove that "calculations of the weight of the earth were found" in the Great Pyramid of Khufu? If von Däniken's theories cannot be demolished by refuting his assertions, we need another line of attack. We must examine not his evidence, but the logical structure of his argument.

The Rorschach Test

Von Däniken's arguments fall into two types. The first is the "looks-like-a-spaceman-to-me" type. Let's examine his most famous case: the relief of the "rocket-driving god" at Palenque.

Palenque is a Late Classic Maya site in Chiapas, Mexico. The stone relief is carved on the limestone sarcophagus lid of Pakal, who died on August 31, A.D. 683. Von Däniken sees a human figure, garbed and antennaed, reclining to manipulate the controls of a spacecraft whose thrusters jet smoke and flame.

Maya scholars see something else entirely. They see Pakal, the central figure, falling backward into the jaws of the underworld. Pakal teeters on the head of the Sun Monster, depicted with a skeletal jaw but a fleshed nose and eyes, suggesting he is poised halfway between the underworld and the living world at the moment of sunset. From a point above Pakal's stomach grows the World Tree of Maya cosmology, a tree that stands at the center of the universe like a fireman's pole, penetrating through the underworld, the middle world of everyday life, and the heavens. The heavens are marked by a Celestial Bird perched on the tree's topmost branch.

Pakal's sarcophagus lid is a statement of the Maya belief that the death of a king nourished the cosmic order.

If a 7th-century Maya artist's carving of his king's death fits a 20th-century European's image of an astronaut, does this provide evidence for von Däniken's case? Consider a hypothetical situation. A young child comes to you and says, "Look. That cloud looks like a doggie." Has that child given you any information about clouds? Has he given you information about dogs? Or has he given you information about himself?

If von Däniken writes that Pakal's sarcophagus lid looks like a spaceman, has he told you anything about Pakal? Has he told you anything about spacemen? Or has he told you something about himself? The "looks-like-a-spaceman" line of argument treats the archaeological record as if it were a Rorschach test. It provides as little evidence about our ancient history as a Rorschach provides about ink and paper.

The Rusty Pillar

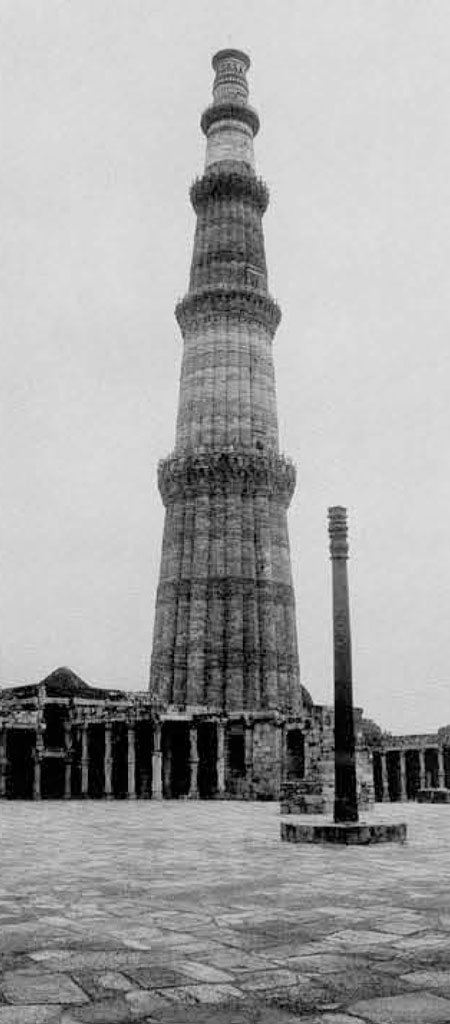

The second type of argument is the "science-cannot-explain-this-mystery-so-spacemen-must-be-responsible" type. Von Däniken writes: "In the courtyard of a temple in Delhi there exists… a column made of welded iron parts that has been exposed to weathering for more than 4,000 years without showing a trace of rust. In addition it is unaffected by sulphur or phosphorus. Here we have an unknown alloy from antiquity staring us in the face."

The Delhi Pillar is a shaft of wrought iron that weighs 6 tons and stands 22 feet high, extending only 20 additional inches into the earth. According to local tradition, the pillar was dhila, or "loose," and so the place where it stood was named Dhili. It has proved stable enough, both architecturally and chemically, to resist the centuries—not 40 centuries as claimed by von Däniken, but 16.

Chiseled into the column's western side is a six-line dedicatory text in Sanskrit datable to the Gupta Dynasty in the early 4th century A.D. The inscription calls the pillar the arm of fame of Raja Dhava, a worshipper of the god Vishnu, and likens the letters cut into its shaft to the swordcuts he inflicted upon his enemies.

Metallurgists analyzed the pillar in 1912 and found it had been made by hammering 80-pound lumps of red-hot iron together, welding them into a single piece. The metal is composed of 99.72 percent pure iron, 0.1 percent phosphorus, and traces of carbon and silica. Sulphur is virtually absent at 0.006 percent.

When present in iron, phosphorus inhibits rust. Recent investigations, however, have concluded that the preservative effect of the phosphorus was overshadowed by other factors. First, the dry, pure climate of Delhi provided protection against rust; heat retention by such a large mass of metal would inhibit condensation of moisture on its surface during cool nights. Second, the pillar was protected by a thin layer of scale produced in forging it. Additional protection may have been provided by a coating built up by periodic ceremonial applications of ghee or vegetable oil during the first 500 years of its existence. Finally, there is a natural tendency for iron to rust at a diminishing rate as corrosion products form on its surface and seal it.

To close the argument, the lower portion of the shaft has been pitted by rust. The mystery that science cannot explain is purely the product of von Däniken's sloppy scholarship. He doesn't get the date right, he's ignorant of the real significance of phosphorus in an iron alloy, he's oblivious to a century of research by legitimate scientists, and he's misinformed about the rust.

When von Däniken writes that science cannot explain something, he seems to mean that he doesn't know enough to account for it himself. Carl Sagan summed up the problem: "Every time he sees something he can't understand, he attributes it to extraterrestrial intelligence, and since he understands almost nothing, he sees evidence of extraterrestrial intelligence all over the planet."

The Missing Facts

Von Däniken's discussion of the colossal stone statues of Easter Island reveals something worse than ignorance. Carving these 30-foot, 50-ton giants from their quarries and hauling them to their stations overlooking the sea were impressive demonstrations of primitive engineering. Von Däniken sets them up as another mystery science cannot explain:

"Even if people with lively imaginations have tried to picture the Egyptian pyramids being built by a vast army of workers using the 'heave-ho' method, a similar method would have been impossible on Easter Island for lack of manpower. Even 2,000 men, working day and night, would not be nearly enough to carve these colossal figures out of the steel-hard volcanic stone with rudimentary tools. No trees grow on the island, which is a tiny speck of volcanic stone. The usual explanation, that the stone giants were moved to their present sites on wooden rollers, is not feasible. Then who cut the statues out of the rock, who carved them and transported them to their sites? How were they moved across the country for miles without rollers? How were they dressed, polished, and erected?"

In this case, von Däniken is not merely careless or ignorant. Perfectly ordinary answers to these questions are clearly documented with photographs in Thor Heyerdahl's book Aku-Aku. This is not an obscure volume. It appeared as the Book-of-the-Month Club Selection for September 1958 and remained on the New York Times Best Seller List for the next 30 weeks. Von Däniken must have known of its contents because he specifically mentions Heyerdahl's archaeological research and cites Aku-Aku in the bibliography of Chariots of the Gods?.

Heyerdahl related the results of experiments he conducted to determine how the statues were carved, raised, and transported. Using hand-held stone picks, a group of six Easter Islanders chipped the outlines of a giant figure into the rockface, splashing the stone with calabashes of water to soften it. Based on their demonstration, Heyerdahl concluded that two six-man teams, working all day in shifts, could carve a medium-sized, 15-foot statue in about a year's time.

Twelve Easter Islanders set a 25-ton statue upright in 18 days using nothing more than three 15-foot wooden levers to pry the giant upward a quarter of an inch at a time, rocks to place under the rising figure, and ropes to topple it into place. Trees to provide the wooden poles have grown around the crater lake at the southwestern tip of the island since before the first people set foot on Easter Island.

Over local protestations that the statues "walked" to their current locations, Heyerdahl demonstrated they could have been simply dragged into position by roping a 15-ton figure to a crude wooden sledge pulled by 180 people. While his experiment proved that the Easter Islanders had needed no extraterrestrial help with transportation, Heyerdahl himself was not satisfied. Recently he announced the results of further research. Based on the suggestion of a Czech engineer named Pavel Pavel, he found that the upright monumental figures could indeed be made to walk by rocking and twisting them from side to side in the same way that a refrigerator can be "walked" into position.

According to Arne SkjOlsvold, Archaeological Field Director of the Heyerdahl/Kon-Tiki Museum Expedition to Easter Island, the statues have such a low center of gravity that they can be tilted up to 30 degrees without toppling. Only 24 men and four ropes were needed to move a 10-ton statue. As confirming evidence, the expedition also found a pattern of damage on the bases of Easter Island's statues that suggests the wear and tear of their long walks.

Von Däniken cannot be faulted for not writing in 1968 about ideas that came to light in 1986. He is accountable, however, for presenting the relevant facts contained in a book he claims to be familiar with.

An Intellectual Line of Defense

When Playboy asked von Däniken whether his convictions as a fraud and embezzler should influence whether people listen to him, he replied: "Many people who have been in jail say they were not guilty. I say the same thing. I have never committed fraud or embezzlement, although it is true I have been convicted of those things. I was improperly convicted three times, but each time for the same thing."

A reader cannot trust von Däniken. He manufactures data and misrepresents data. Sometimes this is due to his ignorance, and sometimes it appears to be due to a deliberate attempt to mislead. Intellectual consumers must realize that popular scientific literature contains many dangerously defective products and must consciously take steps to protect themselves.

The first line of defense against von Däniken, or any other charlatan, is a healthy skepticism. Readers need to remind themselves that asserting something to be true doesn't make it true, and that printing the assertion doesn't make it any truer.

A second intellectual tool is the principle known as Occam's Razor, articulated by William of Occam, who died in 1349: "Never postulate complexity unless it is necessary." Suppose your 6-year-old comes home muddy. The least complex storyline is that he fell in a mud puddle. If he says a dinosaur pushed him in, Occam's Razor suggests the more economical hypothesis is true. Von Däniken claims to bring home a dinosaur, but his evidence is nothing more than his personal assurances that he saw a cloud that looked like one.

A third useful tool is uniformitarianism, the assumption that the universe was formed by the natural operation of forces observable today. Within this context: "Don't postulate miracles unless they are necessary." Like the Roman Catholic Church, we should accept a miracle only after our devil's advocate has exhausted natural explanations.

Armed with skepticism, Occam's Razor, and uniformitarianism, a critical reader can test any piece of popular archaeological literature. These three principles are formal statements of what most thoughtful people already know. Together, they have another name: common sense.

The books of Erich von Däniken are an affront to common sense. Nevertheless, he and his ilk find widespread acceptance, perhaps because people are eager to believe a good story. At first glance, he seems to be telling us of a glorious history, of wonderful times when our planet was important in the universe and our ancestors walked with spacemen or gods.

The appeal of such a story would fade if readers considered its depressing implications. It is based on the assumption that our ancestors were uncreative beings who could only be improved by cross-breeding with better extraterrestrial stock. It requires one to believe that art and science fell from outer space instead of springing from the human heart and brain.

Von Däniken's history is flawed because he has no respect for his facts, and his fairy tales are flawed because he has no respect for his characters. In his view, the people who went before us were not fully human. Archaeology is the story of our ties to our ancestors, and its raw material includes every person, family, village, city, and nation that ever existed. We will never know more than a tiny fraction of that story, but the episodes we carefully piece together carry the hallmarks most prized by storytellers: They really happened—and they happened to people like us.

Comments

Please log in or register to join the discussion