While GNOME's commitment to client-side decorations represents a clear design philosophy, the desktop environment's refusal to support server-side decorations creates significant friction for users, developers, and the broader Linux ecosystem. This analysis examines the technical realities, user experience trade-offs, and ecosystem fragmentation caused by this singular stance, proposing a pragmatic middle path that could benefit all stakeholders without compromising GNOME's core principles.

The debate over window decoration models in Linux desktop environments represents more than a technical implementation choice—it embodies a fundamental philosophical divide about where application boundaries should end and system boundaries should begin. For years, GNOME has stood firm in its commitment to client-side decorations (CSD), where applications draw their own titlebars and window controls, while most other desktop environments, including KDE Plasma, have embraced server-side decorations (SSD), where the compositor draws these elements. This divergence has created a persistent source of friction in the Linux desktop ecosystem, one that affects not just aesthetics but functionality, developer experience, and the platform's overall cohesion.

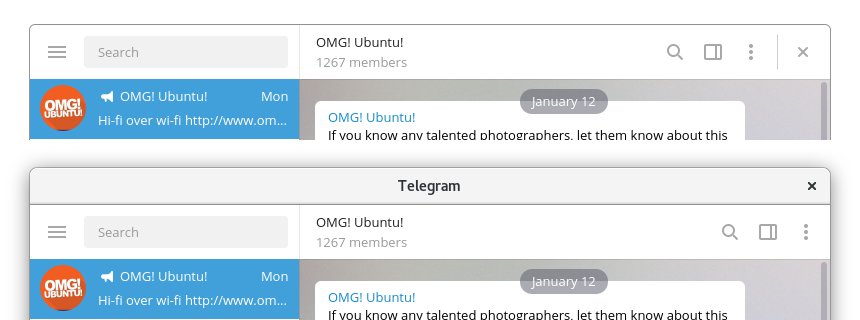

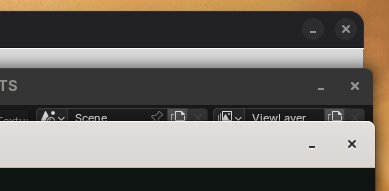

The technical distinction is straightforward but consequential. When an application uses SSD, the window manager or compositor—what we'll refer to as "the system"—draws the titlebar, close/minimize/maximize buttons, and window borders. This approach ensures visual consistency across applications, as all windows share the same decoration style, color scheme, and interaction patterns. The application focuses solely on its content area, while the system handles the chrome. With CSD, the application itself draws these elements, allowing for more flexible designs like the integrated headerbars common in GNOME applications, where the titlebar merges with the application's toolbar.

GNOME's preference for CSD stems from a coherent design philosophy: the application should control its entire visual presentation to create a more immersive, cohesive experience. This approach works beautifully for applications designed with this paradigm in mind, such as those built with GTK4 and libadwaita. These apps feature integrated headerbars that save vertical space and create a unified visual language. However, this philosophy breaks down when applied to the broader ecosystem of Linux applications, many of which were designed with SSD in mind and have no intention of adopting CSD.

The practical consequences of GNOME's SSD refusal manifest most visibly in applications that don't adapt well to CSD. Professional applications like DaVinci Resolve, many CAD tools, and specialized scientific software often expect a traditional window decoration model. When forced to run on GNOME without SSD support, these applications either lack a titlebar entirely or implement a makeshift one that feels alien and often breaks basic window management functions like dragging or resizing. The user experience suffers significantly—windows become difficult to move, screen real estate is poorly managed, and the application feels fundamentally broken.

To work around this limitation, the Linux community developed libdecor, a library that provides a fallback decoration system for applications that need SSD but are running on compositors that don't support it. While libdecor solves the immediate problem of missing titlebars, it creates a new set of issues that highlight why a native SSD implementation would be preferable.

Libdecor essentially creates a hybrid approach that combines the worst aspects of both worlds. Applications using libdecor receive a traditional-looking titlebar that provides the space efficiency and functionality users expect, but this titlebar is drawn by the application rather than the system. This means it lacks the visual consistency of true SSD—the titlebar's appearance varies between applications, doesn't respect system-wide theming, and can't be customized by users through their desktop environment settings. The result is a patchwork of visual styles that undermines the very consistency SSD is meant to provide.

This inconsistency isn't a fault of the libdecor developers, who have done impressive work with limited resources. Rather, it's a symptom of a deeper architectural problem: libdecor is a workaround for an artificial limitation. The library must guess at the system's visual style and implement it in each application, leading to subtle differences in color, spacing, and interaction patterns. When the system itself could provide these decorations natively, the result would be perfect visual and functional consistency.

The argument for SSD support extends beyond fixing broken applications. It touches on fundamental questions about what makes software feel "native" to a platform. On Windows and macOS, applications can implement custom titlebars that respect the platform's design language—spacing, button positions, and interaction patterns are consistent even when the titlebar is custom-drawn. This works because these platforms provide clear specifications for how custom decorations should behave. The Linux desktop, by contrast, is a fragmented landscape where each desktop environment has its own design language and expectations.

For applications that want to feel truly native on Linux, they would need to implement multiple decoration styles for different desktop environments—an impractical burden for most developers. This fragmentation makes the Linux desktop less attractive to application developers, particularly those from proprietary software companies who might otherwise consider porting their applications to Linux. The current situation forces developers to choose between supporting only GNOME (with CSD) or only other desktops (with SSD), or maintaining two separate code paths.

The user experience implications are equally significant. Many users who choose desktop environments other than GNOME do so because they value titlebar consistency across all applications. For these users, seeing a GNOME app with an integrated headerbar while everything else uses traditional decorations creates visual dissonance. Some users also view SSD as an accessibility feature—consistent window controls in predictable locations help users with motor impairments or cognitive differences navigate applications more reliably.

The counterarguments from GNOME's perspective deserve serious consideration. The primary technical objection is that server-side decorations, implemented through the xdg-decoration Wayland protocol, are technically "out of specification." Wayland was originally designed with the expectation that all decorations would be client-side, and xdg-decoration exists as an extension rather than a core protocol. GNOME developers argue that supporting non-standard protocols sets a problematic precedent and could lead to fragmentation of the Wayland ecosystem.

This argument has merit in principle, but it doesn't hold up to scrutiny in practice. First, xdg-decoration is not an obscure or experimental protocol—it's implemented by every major production-ready Wayland compositor except mutter, including KWin (KDE), wlroots (used by Sway, Hyprland, and others), and Mutter's own implementation in GNOME's experimental branches. It has become a de facto standard through widespread adoption. Second, Wayland's evolution has always involved adopting extensions to meet real-world needs. The protocol now supports screen sharing, global keyboard shortcuts, and other features that weren't in the original design—GNOME itself has adopted many of these extensions.

The security and design concerns that might justify rejecting a protocol don't apply to xdg-decoration. Unlike protocols that could compromise system security or violate design principles, xdg-decoration simply allows applications to request that the system draw their window decorations. It doesn't grant special privileges or create security vulnerabilities. The protocol is already trusted enough that every other desktop environment uses it in production.

The philosophical objection—that window decorations are part of the application, not the system—represents a genuine difference in design philosophy. Some developers and users genuinely believe that applications should control their entire presentation, and this perspective has validity. However, this philosophical stance becomes problematic when it prevents users from making their own choices about their desktop experience.

The comparison to file choosers is instructive. GNOME supports the xdg-desktop-portal file chooser protocol, allowing applications to use either the system file picker or implement their own. This approach respects both philosophies: applications that want to provide a custom file picker can do so, while applications that prefer consistency can use the system picker. Users benefit from having options, and developers aren't forced into a single approach. Extending this same flexibility to window decorations would allow applications to choose between SSD and CSD based on their needs and preferences.

A practical implementation of SSD support in GNOME would need to balance several competing requirements. The most straightforward approach would be for mutter to implement the xdg-decoration protocol and enable SSD by default for applications that don't explicitly request CSD. This would immediately solve the compatibility issues with existing applications while preserving the CSD experience for apps designed for it.

Crucially, this implementation should respect application preferences. Applications that are designed with integrated headerbars, like native GNOME apps, would continue to use CSD by default. The system would only provide SSD when an application requests it or when the application doesn't specify a preference. This maintains the current behavior for GNOME's own applications while extending support to the broader ecosystem.

For users who want even more control, the implementation could include a system setting to force SSD on all applications, including GNOME apps. In this scenario, GNOME applications would remove their integrated headerbars and rely on system-drawn decorations. While this would change the visual design of GNOME apps, it would provide consistency for users who prioritize that over the integrated design. Conversely, users on other desktops who want to force CSD on GNOME apps could do so through their own desktop environment's settings, as many already support this through various workarounds.

This flexible approach would create a win-win situation. Users of other desktops would see consistent titlebars across all applications, including GNOME apps. Developers of non-GNOME applications would have a reliable way to ensure their applications work properly on GNOME without implementing libdecor workarounds. The Linux desktop ecosystem would become more cohesive, reducing the fragmentation that currently makes platform development challenging.

The broader implications for the Linux desktop ecosystem cannot be overstated. Linux already faces challenges in attracting application developers and users, partly due to fragmentation. When a major desktop environment like GNOME refuses to support a widely adopted protocol, it creates additional barriers. Developers must choose between supporting GNOME or supporting the rest of the Linux desktop, or they must implement complex workarounds. This fragmentation makes Linux less attractive for commercial software development and creates a vicious cycle where the lack of commercial applications further limits Linux adoption.

GNOME's current stance on SSD represents the single most significant barrier to a more unified and user-friendly Linux desktop experience. While the philosophical commitment to CSD is understandable and has produced beautiful, cohesive applications, the refusal to support SSD creates unnecessary friction for users, developers, and the ecosystem as a whole. The solution isn't to abandon CSD but to embrace flexibility—allowing applications and users to choose the decoration model that works best for their needs.

The path forward requires recognizing that design philosophy and practical compatibility need not be mutually exclusive. By implementing xdg-decoration support with sensible defaults that respect application preferences, GNOME could maintain its design vision while dramatically improving the experience for the broader Linux ecosystem. This isn't about compromising principles—it's about acknowledging that different applications have different needs, and that a mature desktop environment should support multiple approaches rather than enforcing a single paradigm.

The Linux desktop has evolved through collaboration and compromise, with different projects bringing different strengths to the ecosystem. GNOME's contribution to design thinking and user experience has been invaluable, but its refusal to support server-side decorations has become an outlier in an otherwise increasingly cohesive ecosystem. The time has come for this barrier to fall, allowing the Linux desktop to move forward with greater unity and better experiences for all users.

For those interested in the technical details of the xdg-decoration protocol and its implementation, the Wayland protocol documentation provides comprehensive specifications. The libdecor project offers insight into the current workaround solution, while discussions on the GNOME GitLab reveal the ongoing debate within the GNOME community. Understanding these resources helps illuminate both the technical feasibility and the philosophical dimensions of this critical desktop issue.

Comments

Please log in or register to join the discussion