Surface parking lots in American downtowns are more than just eyesores—they actively drain economic value from cities by blocking productive development on valuable land.

Cities are living organisms, constantly evolving and adapting to the needs of their inhabitants. Yet, in many American downtowns, a peculiar phenomenon persists: vast expanses of surface parking lots that seem to defy the economic logic of urban development. These asphalt deserts, often occupying prime real estate, are more than just eyesores; they are actively draining the economic potential of our cities.

The Economic Drain of Parking Lots

To understand the true cost of surface parking lots, we need to look at how cities generate value. A city is, fundamentally, a fixed plot of contiguous land. The value of this land is derived from its productive potential. If a plot of land can yield $10 million a year if developed, it would command a much higher price than a plot capable of generating only a few thousand dollars.

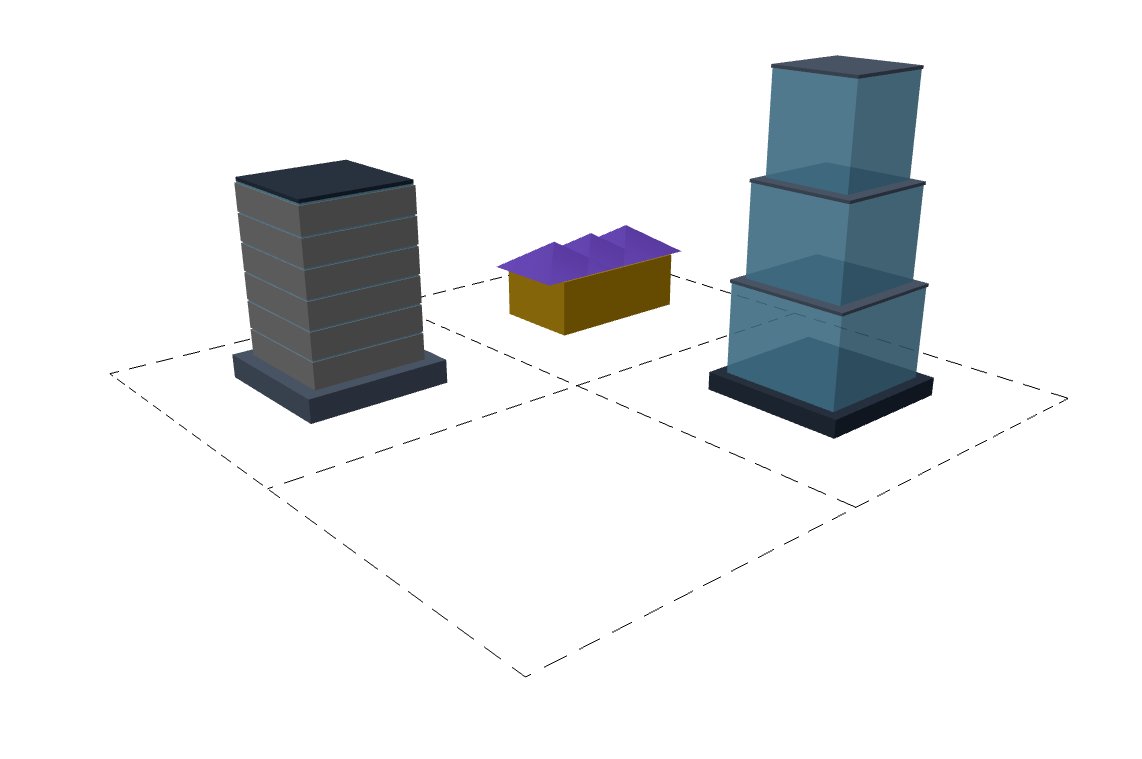

In a sensible market, we would expect development to track with the land value, because higher land prices imply higher annual returns from building on that land. However, many American downtowns look like this:

This simplified downtown features a mix of multifamily apartments and offices with rowhomes around the corner. Yet, right in the middle is an empty plot of land dedicated solely for parking cars.

Measuring Economic Contribution

To quantify the impact of different land uses, we can measure the net economic contribution of each parcel. This is calculated as:

Net Contribution = (Economic Output in $) - (Land Value in $)

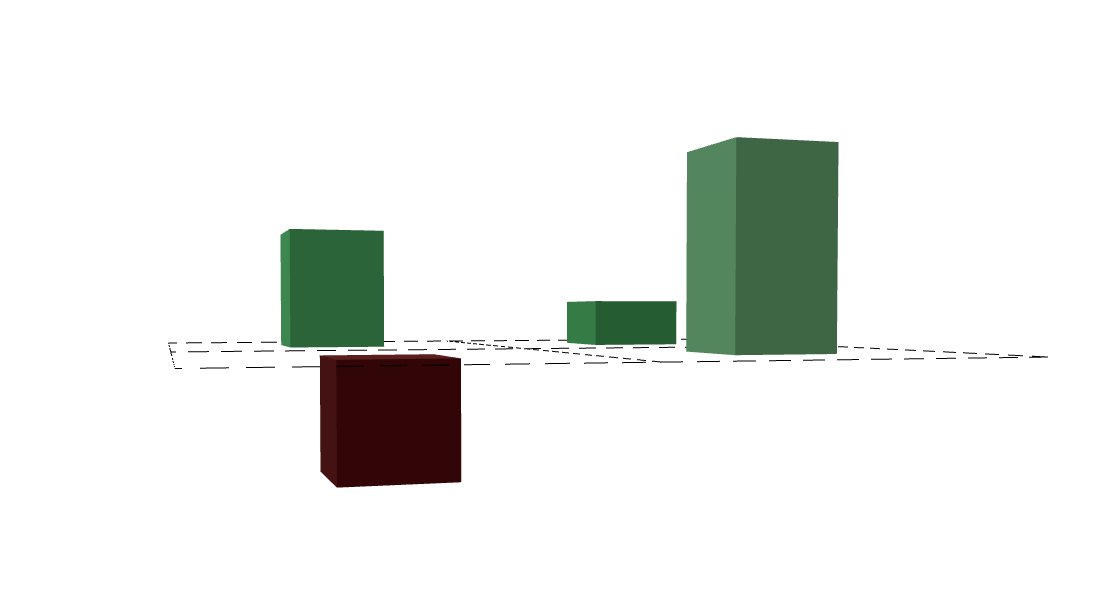

When we visualize this data, the results are striking:

The office building, filled with workers and transactions, generates far more in economic activity and value creation than its land value and, therefore, rises the highest. The apartment, where dozens of residents live, stands nearly as high. The rowhomes add steady, smaller value. But the parking lot does something different. It dips below the surface, shown as a red bar sinking into the ground.

Why below ground? Because in economic terms, a parking lot doesn't simply fail to add value; it actively subtracts value. Every year it sits idle, it consumes some of the most valuable land in the city. When valuable downtown land lies idle, it blocks the housing, jobs, and amenities that could exist there. The costs ripple outward: higher rents, longer commutes, fewer opportunities nearby. What could have been a productive part of the community instead becomes a hole in its fabric.

In other words, the parking lot isn't a neutral space. It's a drain. It pulls the city's potential downward, both visually and economically.

The Syracuse Example

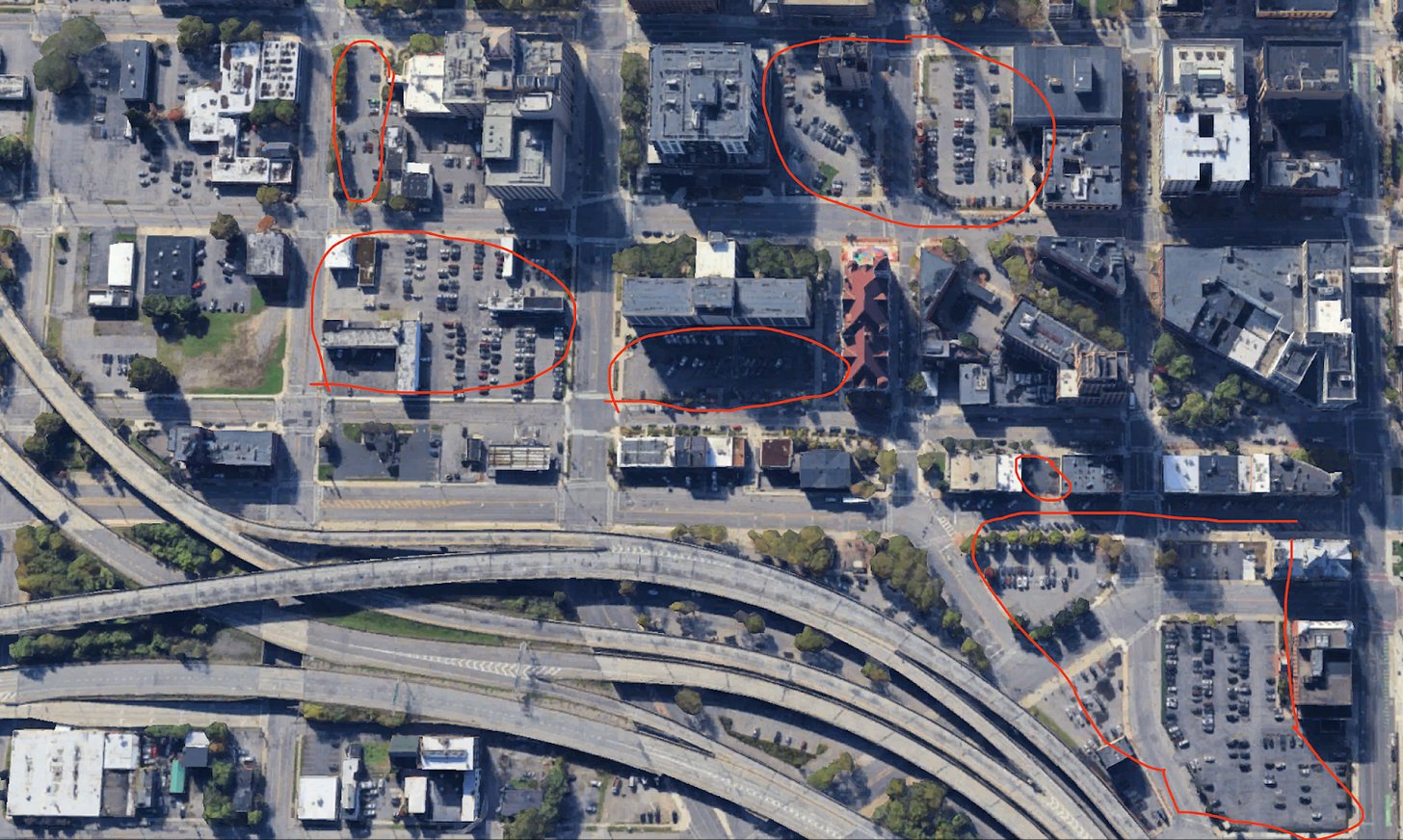

To illustrate this point, let's look at Syracuse, New York. Despite its history of de-industrialization, Syracuse still has a charming and nicely developed downtown. Nevertheless, Syracuse shares a problem endemic to most modern American cities: excessive parking lots in prime downtown locations.

In Syracuse, parking lots add up to $44 million in non-exempt land value—6% of the city's total land value. This figure only counts parcels where the sole use case was parking. There are plenty more commercial parcels with large parking lots not counted in that figure.

The most valuable land is concentrated in downtown, where the most economic activity occurs. Yet, from an aerial view, you can see many large parking lots that should not exist in a bustling downtown area.

Why Do Parking Lots Persist?

Given the economic inefficiency of surface parking lots, one might wonder why they persist. The answer lies in the financial incentives created by our current property tax system.

A parking lot generates some revenue every year, but nothing like the revenue or profit the lot could generate if developed. So why don't parking lot owners develop their land to its highest and best use? The reason is because leaving the lot empty is easy—the parking lot owner generates steady revenue, and all the while the land underneath the parking lot continues to rise in value, yielding speculative gains.

Meanwhile, the parking lot owner's holding costs are small. Sure, they have to do the bare minimum to maintain a surface parking lot, and perhaps pay someone for staffing and enforcement, but otherwise their revenues are more than sufficient to cover the costs. Most importantly, their property taxes are far lower than if they developed the lot, as the property tax taxes both land and improvements.

The Tax Disparity

To illustrate this point, let's compare the property taxes paid by different types of properties in Syracuse:

- Office building: $3.78 per square foot

- Multifamily housing unit (with PILOT agreement): $1.68 per square foot

- Surface parking lot: $0.71 per square foot

The parking lot pays nearly ten times less than either building. Our property tax policy punishes buildings and does not inflict enough cost on underutilized land. The result is a system that rewards holding valuable sites idle while penalizing those who invest, build, and contribute to the city's productivity.

Solutions: Beyond Parking Reform

Parking reform has become a hot topic in many urban cities, led in part by the Parking Reform Network. They have focused their efforts primarily in three areas:

Eliminate parking requirements: Many cities historically required developers to build a certain number of parking spaces per housing unit or square foot of retail. Removing these "minimums" lets builders decide how much parking is truly needed instead of top-down planning, reducing wasted land and construction costs.

Establish parking maximums: In areas where land is especially valuable or where walkability and transit are strong, cities can instead set an upper limit on how much parking may be built. This prevents the over-supply of parking that undermines density and urban design.

Smart street parking: Curbside spaces can be priced dynamically or managed with time limits and residential permits so that parking remains available but doesn't encourage endless circling or long-term storage of cars in prime locations.

These policies are not only good, but also politically pragmatic. However, in many of our urban cities, the problem stretches beyond what these simple reforms are able to tackle. In the Syracuse examples, for instance, the parking lots are not caused by parking mandates from central planners. Instead, they are created by distorted incentives.

The Land Value Tax Solution

The most effective solution to this problem is to shift taxes away from buildings and onto the unimproved value of land. By increasing the tax on land value, the parking lot owner's annual costs increase and the speculative reward for holding the land out of use decreases.

This approach, known as Land Value Tax (LVT), would:

- Make it financially unsustainable to hold valuable downtown land as surface parking

- Encourage development of the highest and best use for each parcel

- Reduce speculation in land markets

- Generate more revenue for cities without penalizing productive activity

Conclusion

Surface parking lots are more than just a visual blight on our cities; they are actively draining economic potential from our most valuable urban spaces. By understanding the economic impact of these lots and the incentives that create them, we can begin to implement solutions that will transform our downtowns into more vibrant, productive, and livable spaces.

The path forward is clear: we need to stop incentivizing surface parking lots and start encouraging the development of our most valuable urban land. Whether through parking reform, land value taxation, or a combination of approaches, the goal is the same—to create cities that work better for everyone.

Comments

Please log in or register to join the discussion