John Rauser's classic RPubs article dismantles a common statistical misconception: the mathematical impossibility of meaningfully averaging percentiles. Through clear examples and visual demonstrations, the piece reveals how percentile averaging produces distorted results that violate fundamental statistical principles, offering crucial insights for anyone working with ranked data.

The Mathematical Deception of Percentile Averages

John Rauser's 2014 RPubs article "You CAN Average Percentiles" presents a deceptively simple yet profound statistical insight: while you can mathematically calculate an average of percentiles, the result is statistically meaningless. This counterintuitive truth challenges a common practice in data analysis and reveals fundamental misunderstandings about what percentiles represent.

Understanding Percentiles as Rankings, Not Measurements

A percentile is fundamentally a ranking position within a dataset, not an absolute measurement. When we say a student scored in the 90th percentile on a test, we mean they performed better than 90% of test-takers. This is a relative position, not an absolute score. The critical distinction lies in the fact that percentiles are ordinal data—they convey order but not magnitude between values.

Rauser demonstrates this through a simple thought experiment. Consider two datasets: one with scores [10, 20, 30, 40, 50] and another with scores [10, 100, 1000, 10000, 100000]. A student scoring 30 in the first dataset would be at the 60th percentile. A student scoring 1000 in the second dataset would also be at the 60th percentile. If we average these percentiles (60 and 60), we get 60. But what does this mean? The actual scores (30 and 1000) differ by a factor of over 30, yet their percentile positions are identical. The average percentile tells us nothing about the actual performance difference.

The Mathematical Impossibility of Meaningful Averages

Percentile averaging violates several statistical principles:

Non-linear Scaling: Percentiles transform data through a non-linear ranking function. The distance between percentiles doesn't correspond to constant differences in the underlying measurements. The gap between the 90th and 95th percentiles might represent a tiny score difference in one dataset and a massive difference in another.

Distribution Dependence: Percentile values are entirely dependent on the distribution of the dataset. The 50th percentile (median) of a normal distribution differs dramatically from the 50th percentile of a lognormal distribution, even if both have the same mean. Averaging percentiles across different distributions produces meaningless composite values.

Loss of Information: When we convert measurements to percentiles, we discard information about the actual scale and spread of the data. Averaging these reduced representations compounds the information loss.

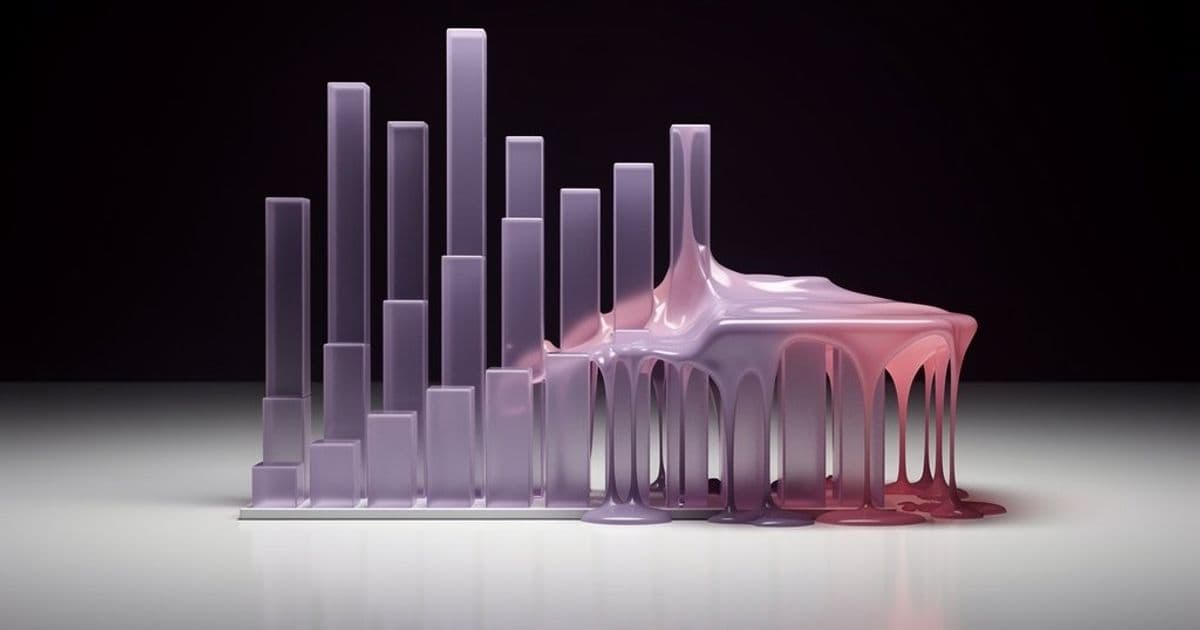

Visual Demonstration of the Problem

Rauser's article includes visualizations that make this abstract concept concrete. By plotting actual scores against their percentile positions, we see the characteristic S-shaped curve of the cumulative distribution function. This curve reveals how percentiles compress or expand the scale depending on where you are in the distribution.

In the left tail of a normal distribution, small score changes produce large percentile jumps. In the middle, the relationship is more linear. In the right tail, large score changes produce small percentile movements. Averaging percentiles from different parts of this curve mixes fundamentally different relationships between score and rank.

Practical Implications for Data Analysis

This insight has significant implications for how we analyze and report data:

In Education: When schools compare student performance across different tests using percentile ranks, they cannot meaningfully average these percentiles to create a composite score. A student at the 80th percentile on one test and the 70th on another isn't necessarily at the 75th percentile overall.

In Healthcare: Percentile-based growth charts (like those for children's height and weight) cannot be averaged across different metrics. A child at the 60th percentile for height and 40th for weight doesn't have an "average percentile" of 50th.

In Business Analytics: When comparing performance metrics across different departments or time periods, averaging percentile ranks obscures the actual business impact. A sales team at the 90th percentile in one quarter and the 70th in another doesn't have an average performance of the 80th percentile.

What Should We Do Instead?

Rauser's article implicitly suggests better approaches:

Work with Original Measurements: When possible, analyze and average the actual measurements rather than their percentile ranks. This preserves the scale and meaning of the data.

Use Standardized Scores: For comparing across different distributions, consider z-scores or other standardization methods that preserve more information than percentiles.

Report Percentiles with Context: When reporting percentiles, always include information about the reference distribution. The 90th percentile means different things in different contexts.

Visualize the Distribution: Show the full distribution rather than reducing it to summary percentiles. This provides more complete understanding.

The Broader Statistical Lesson

Rauser's simple demonstration reveals a deeper truth about statistical analysis: not all mathematical operations produce meaningful results. Just because you can calculate something doesn't mean you should. Percentile averaging is a perfect example of a "mathematically valid but statistically meaningless" operation.

This insight extends beyond percentiles to other ranked or ordinal data. Averaging ranks, averaging ratings on different scales, or averaging scores from different tests all suffer from similar problems. The key is understanding what your data actually represents before applying mathematical operations.

Conclusion

John Rauser's RPubs article serves as a crucial reminder that statistical literacy requires understanding the meaning behind the numbers. Percentile averaging seems intuitive—after all, we average other measures routinely—but it violates the fundamental nature of what percentiles represent. The next time you encounter averaged percentiles in reports or analyses, remember Rauser's lesson: you can calculate them, but you probably shouldn't.

For those interested in exploring this further, Rauser's original RPubs article provides interactive examples and visualizations that make these concepts tangible. The article stands as an excellent educational resource for anyone working with ranked data or teaching statistical concepts.

Related Resources:

- John Rauser's original RPubs article

- RStudio's RPubs platform for sharing R analyses

- Understanding Percentiles - Statistical concepts explained

- The Problem with Averaging Percentiles - Academic discussion of the issue

Comments

Please log in or register to join the discussion