The U.S. Department of Commerce has introduced a narrow, compliance-heavy framework allowing limited exports of specific AI accelerators to China and Macau, but the stringent supply-first requirements and licensing hurdles are designed to benefit established giants like Nvidia and AMD while sidelining smaller competitors.

The U.S. Department of Commerce's Bureau of Industry and Security (BIS) has published a new set of export regulations for advanced AI and high-performance computing (HPC) processors destined for China and Macau. This move does not represent a broad reopening of the market for cutting-edge American silicon. Instead, it establishes a tightly controlled, case-by-case licensing regime that allows only specific, lower-performance accelerators to be shipped, provided they meet a complex set of conditions that inherently favor large, established semiconductor manufacturers.

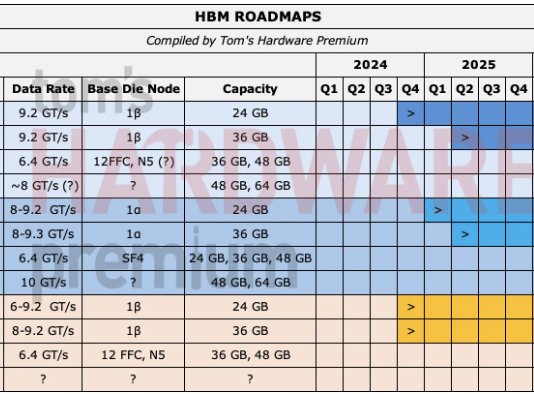

The new rules are predicated on two technical thresholds: a total processing performance (TPP) of less than 21,000 and a total DRAM bandwidth below 6,500 GB/s. The BIS explicitly cites AMD's Instinct MI325X and Nvidia's H200 GPUs as examples of products that could qualify. For context, the MI325X delivers 1,300 TFLOPS of FP16 performance, yielding a TPP score of 20,800, while the H200 offers 989.5 FP16 TFLOPS for a TPP of 15,832. Both fall under the limit. Their memory configurations also comply: the MI325X features 256 GB of HBM3E with 6 TB/s of bandwidth, and the H200 carries 141 GB with 4.8 TB/s. Any product exceeding these thresholds, or any re-export involving countries in Group D:5 (including Russia, Iran, North Korea, and Belarus), remains subject to a presumption of denial.

However, the technical specs are only the entry point. The true barrier lies in the supply chain and compliance mandates. The policy is fundamentally structured to ensure that U.S. demand is met before any international shipments occur. Exporters must prove that U.S. orders are fully satisfied, that no domestic shipments are delayed, and that no advanced-node foundry capacity is diverted to serve foreign markets. Crucially, shipments to China cannot exceed 50% of the volume of the same product sold into the United States. This "U.S. supply-first" requirement effectively turns China into a spillover market for companies like AMD and Nvidia, where exports are permissible only after American needs are secured.

For smaller manufacturers and startups, this creates a nearly insurmountable hurdle. To qualify, a company must first compete successfully in the U.S. market against giants like Nvidia and AMD—likely on price—and then navigate a costly and time-consuming licensing process. The requirement to ship at least as many units to the U.S. as to China means that a small firm, which may have limited production capacity and sales channels, would struggle to meet the volume thresholds that trigger the export license. The policy, therefore, structurally advantages companies with established U.S. sales volumes and the legal and compliance resources to manage the licensing process.

The compliance burden is further intensified by mandatory third-party verification. Every shipment must be tested and certified by an independent laboratory headquartered in the U.S., with no financial or ownership ties to the exporter or any party to the transaction. All testing must occur within the U.S. to confirm that specifications like TPP, memory bandwidth, and interconnect speeds remain within the declared limits. The BIS retains the authority to revoke a lab's qualification at any time, adding a layer of operational risk. This requirement not only adds cost and delay but also centralizes control, as the BIS can suspend case-by-case reviews for any exporter using a de-certified lab.

Beyond hardware specs, the rules impose extensive "Know Your Customer" (KYC) and end-use verification. Exporters must confirm that the accelerators are not destined for military, intelligence, nuclear, missile, or chemical/biological weapons applications. They must provide detailed descriptions of the physical security measures at the receiving facility. If the hardware is deployed in an Infrastructure-as-a-Service (IaaS) cloud environment, the exporter must disclose all remote end-users located in restricted jurisdictions and ensure the IaaS provider prevents unauthorized remote access. The transfer of trained model weights or algorithms to undisclosed or prohibited users is explicitly barred.

This framework reveals the policy's true intent: it is not a trade liberalization but a strategic tool to manage the pace of AI development in China while preserving the commercial presence of U.S. firms. By allowing exports of older or lower-performance accelerators like the H200 and MI325X, the U.S. can generate revenue from its domestic champions and prevent the complete erosion of their market share in China. Simultaneously, it ensures that China's access is constrained to technology that is no longer at the leading edge, maintaining a strategic gap. The rules effectively outlaw the practice of selling China-only, cut-down SKUs unless those same products are also available in the U.S. market, closing a loophole that previously allowed for tailored exports.

For the broader semiconductor ecosystem, the implications are clear. Incumbents with deep U.S. sales pipelines, robust compliance departments, and established relationships with approved testing labs will be best positioned to navigate this new landscape. Companies like Nvidia and AMD can seek licenses for specific products, but the volume will be carefully capped and contingent on domestic supply. Smaller players, including AI startups and specialized accelerator firms, will find the path to the Chinese market effectively closed, not by performance limits alone, but by the structural and financial barriers embedded in the licensing regime. The new rules solidify the dominance of a few large U.S. semiconductor firms in the global AI accelerator market, using export controls as a lever to shape both national security and commercial outcomes.

Comments

Please log in or register to join the discussion