Computer science reveals how data storage involves fundamental trade-offs between speed, memory, and organization, with structures like hash tables and heaps optimizing for different scenarios.

In data storage, sometimes it’s best to embrace a bit of disorder.

Just as there’s no single best way to organize your bookshelf, there's no universal solution for storing information. When creating a digital file, computers must rapidly find storage space and later quickly locate data for deletion. Researchers design data structures to balance addition time, removal time, and total memory consumption.

Imagine organizing books on a shelf: Alphabetical order enables quick retrieval but slow insertion. Random placement speeds up additions but complicates finding specific books. This insertion-retrieval trade-off worsens with scale. Alternatively, using 26 bins for author initials makes insertion and retrieval nearly instantaneous—until one bin becomes overcrowded while others sit empty, recreating the original problem with added clutter.

The Hash Table Solution

Computer scientists use hash tables to address these challenges. These structures calculate storage locations using hash functions—mathematical operations that transform keys (like author names) into bin addresses. A basic hash function might:

- Convert each letter to its alphabet position

- Sum these values

- Divide by 26

- Use the remainder (0-25) as the bin number

Well-designed hash functions distribute items evenly across bins. More bins reduce retrieval time but increase unused space, creating a fundamental space-time trade-off. Over 70 years after their invention, hash tables still reveal new properties: Researchers recently created one with optimal space-time balance, while an undergraduate disproved long-held assumptions about search times in near-full tables.

Prioritizing With Heaps

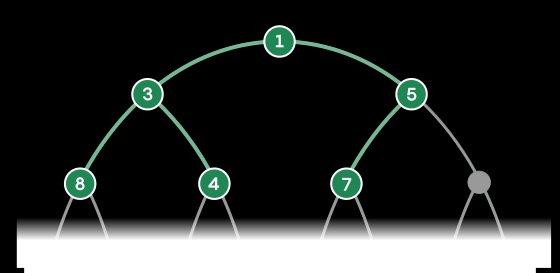

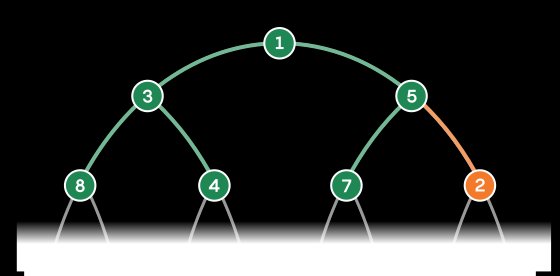

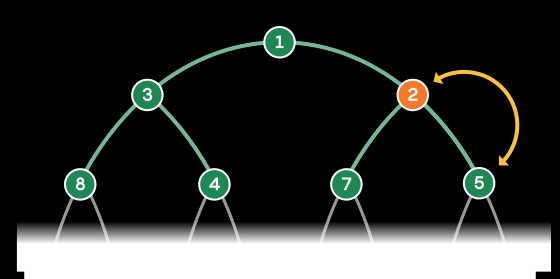

When retrieval order depends on priority (like task deadlines), heaps offer efficiency. This structure resembles a disorderly pile where high-priority items rise to the top. Implemented through binary trees—networks where each node connects to two lower nodes—heaps ensure the most urgent item remains accessible.

Each item enters at the bottom layer and swaps upward until positioned below higher-priority items. Adding a new task to a 1,000-item heap requires at most nine swaps. Removing the top item triggers reorganization where the new priority rises from below.

Each item enters at the bottom layer and swaps upward until positioned below higher-priority items. Adding a new task to a 1,000-item heap requires at most nine swaps. Removing the top item triggers reorganization where the new priority rises from below.  This efficiency enables applications like shortest-path algorithms, where a 2024 heap redesign achieved theoretical optimality for network navigation.

This efficiency enables applications like shortest-path algorithms, where a 2024 heap redesign achieved theoretical optimality for network navigation.

There's no perfect organizational solution—every approach involves compromises. But when some items matter more than others, embracing strategic disorder can be the optimal choice.

Comments

Please log in or register to join the discussion