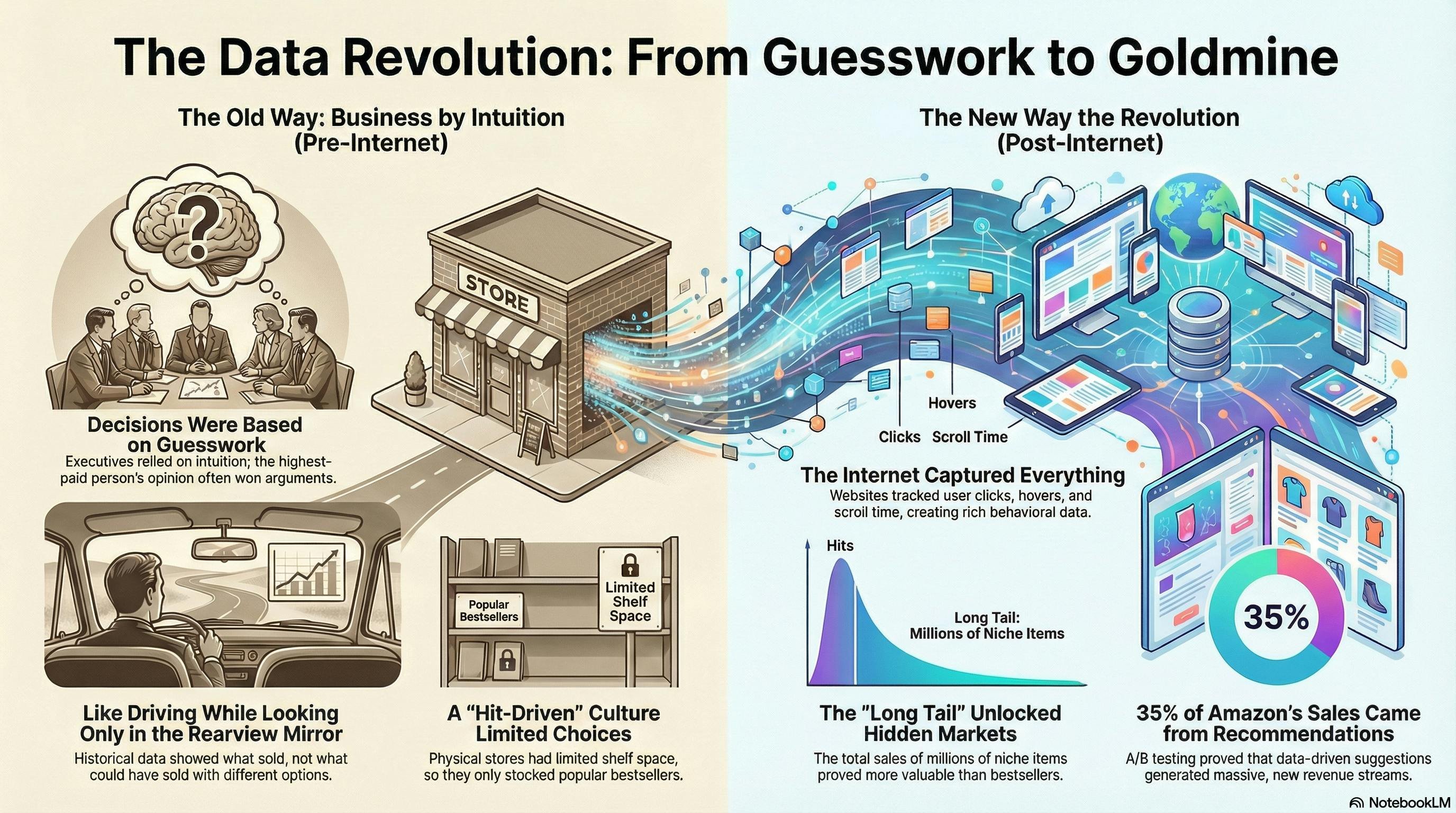

The shift from intuition-based business to data-driven decision-making wasn't gradual—it was a revolution powered by three counter-intuitive discoveries that transformed how companies understand customer behavior and generate revenue.

The modern data-driven world feels inevitable, but it was built on a series of surprising insights that challenged centuries of business intuition. When Amazon first launched, it didn't just sell books—it accidentally discovered that the data from customer hesitation and desire was more valuable than the sales themselves. This wasn't a planned evolution; it was a series of revelations that fundamentally changed what businesses could know about their customers.

The First Discovery: Intention Data Over Transaction Data

The most fundamental shift came from a simple change in venue: moving from physical stores to online platforms. A pre-internet retailer only knew what a customer ultimately bought—the final transaction receipt. An online store, however, could track something far more valuable: user behavior and intent.

Consider a shopper in a 1980s grocery store. They walk past the bakery, stare at a chocolate cake for three seconds, reach for it, and then put it back, perhaps because of the price. In the physical world, that moment of hesitation, desire, and decision is lost forever. The shopkeeper only knows the customer didn't buy the cake.

On the web, this invisible data becomes a goldmine. Using JavaScript code running directly in a user's browser, businesses could suddenly track behaviors that were previously invisible. They could see how long a user hovers their mouse over a button—a reliable proxy for what they are looking at, as research shows a strong correlation between where people look and where they rest their cursor. They could track when someone removes an item from their shopping cart, or even which specific parts of a webpage are visible on their screen.

This ability to capture hesitation and desire—not just completed transactions—allowed businesses to build a much richer, more accurate picture of human behavior. The data revealed patterns that sales figures alone could never show: which products attracted attention but failed to convert, which price points caused hesitation, and which combinations of items customers considered together.

The Second Discovery: The Long Tail Economics

For centuries, physical stores operated under a core constraint: limited shelf space. This forced them to stock only the most popular "hits"—the bestsellers and blockbusters that were guaranteed to sell. This created a hit-driven culture where everyone tended to read the same books and watch the same movies because those were the only options widely available.

The internet destroyed geography and, with it, the limitation of shelf space. Companies like Amazon and Netflix could stock millions of niche items in massive, centralized warehouses. This gave rise to a powerful economic concept known as the "Long Tail," a term popularized by Chris Anderson in his 2004 book.

While each niche item—like a documentary on 1920s architecture or a specific cable for a 2005 printer—sells very little on its own, their combined sales volume can equal or even exceed the total volume of the bestsellers. People didn't only want hits. They bought hits because that was all they were offered.

The business advantage was surprising but profound. Competition for popular "hits" is fierce, forcing retailers to lower prices and accept razor-thin profit margins. In contrast, niche items have very little competition. If you're the only store selling a rare book, you don't have to offer a discount. In fact, the data proved this out: Amazon makes more profit on a rare book than on a bestseller. The "misses" weren't just a curiosity; they were a more profitable business model.

The Third Discovery: Recommendations as a Science Experiment

Once companies like Amazon realized the power of their massive catalog, the next challenge was helping customers discover relevant items within it. They didn't just guess that product recommendations would work; they treated it like a formal science experiment using a method called A/B testing.

The mechanics of their test were simple but brilliant. They split their website visitors into two groups:

- Control Group A: Saw the standard homepage, featuring sections like "New Releases."

- Test Group B: Saw a new homepage with a section for personalized recommendations, such as, "Because you bought a phone, you might like this phone case."

The company then measured a single key metric: the "conversion rate," which tracks how many visitors actually bought something. The results were staggering. The group that received personalized recommendations bought significantly more.

Eventually, Amazon revealed that a massive 35% of their total sales came from these recommendations. This was a watershed moment. It proved that data wasn't just a byproduct of doing business; it was a core asset that could be used to generate a massive chunk of revenue that "simply wouldn't exist without that data."

Recommendations weren't a friendly feature—they were a scientifically validated engine for growth. This approach moved business decisions from boardroom debates to controlled experiments where data provided the answers.

The Pattern: From Artifact to Asset

These three discoveries share a common thread: they transformed data from a passive byproduct into an active business asset. Before the internet, data was something businesses collected after the fact—sales reports, inventory counts, financial statements. It was historical record-keeping.

The new approach made data predictive and prescriptive. It could anticipate what customers wanted before they knew it themselves. It could identify profitable niches that traditional retail would never stock. It could systematically test and validate business hypotheses.

This shift required new infrastructure. Companies needed to capture behavioral data in real-time, store it at scale, and process it quickly enough to influence decisions. This drove the development of data warehouses, analytics platforms, and eventually machine learning systems.

The Modern Implications

Today, these discoveries have evolved into sophisticated systems. Netflix's recommendation engine uses hundreds of data points per user, from viewing history to time of day to device type. Amazon's algorithm considers not just what you bought, but what you viewed, how long you looked, and what other customers with similar patterns purchased.

The long tail concept has expanded beyond products to content. Spotify's catalog contains over 100 million tracks, most of which receive few streams individually but collectively form a massive market. YouTube's creator economy thrives on niche content that would never survive traditional broadcast television.

A/B testing has become standard practice across the tech industry. Companies like Google, Facebook, and Microsoft run thousands of experiments simultaneously, making decisions based on statistical significance rather than executive opinion.

The Next Frontier

The modern, hyper-personalized world wasn't built by accident. It stands on the foundation of these three powerful insights: that a customer's intention is more valuable than their transaction, that the "misses" can be more profitable than the "hits," and that data's value can be scientifically proven and engineered into a core business asset.

These insights from the early 2000s reshaped commerce forever. Now that businesses can analyze not just our actions but our intentions, the next great data-driven shift will likely involve predictive modeling that anticipates needs before they're even expressed, and ethical frameworks that balance personalization with privacy.

The journey from intuition to insight continues, but it's built on these three foundational discoveries that turned online data into a business superpower.

Comments

Please log in or register to join the discussion