In February 1971, a Santa Clara judge authorized the seizure of punch cards and a 'computer memory bank' – establishing foundational principles for digital forensics that remain relevant amid today's complex data privacy debates.

On February 19, 1971, a Santa Clara County judge approved what is recognized as the first computer search warrant in history. The order permitted Oakland Police to enter offices in Palo Alto and residences in Menlo Park to seize physical documents alongside intangible digital assets – specifically "computer printout sheets" and a "computer memory bank or other data storage devices." This landmark legal action occurred during investigations into the alleged theft of a $15,000 ($120,000 today) remote-plotting system from University Computing Company, highlighting early struggles to reconcile traditional property law with emerging computing paradigms.

The Tangible Foundations of Digital Evidence

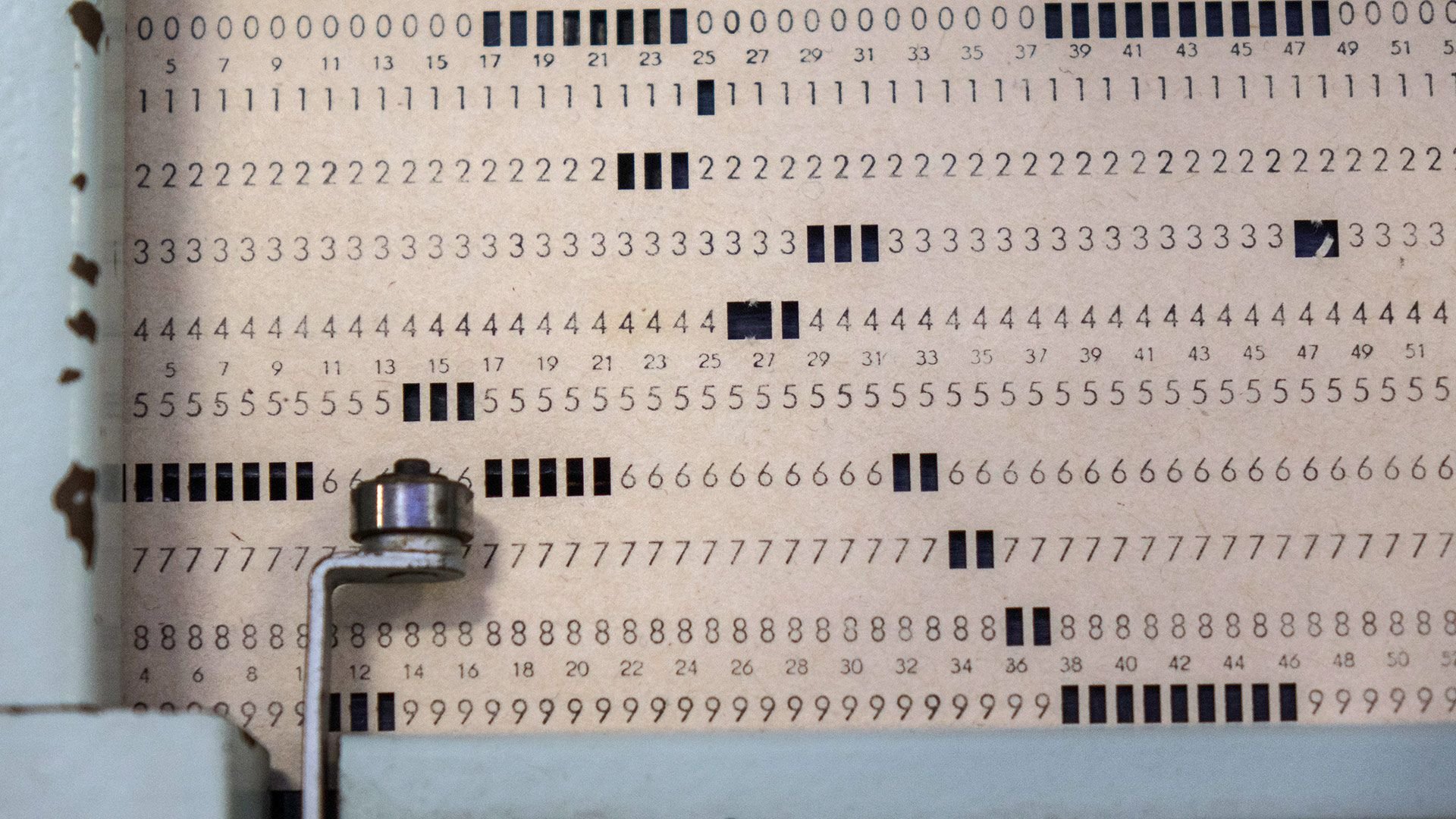

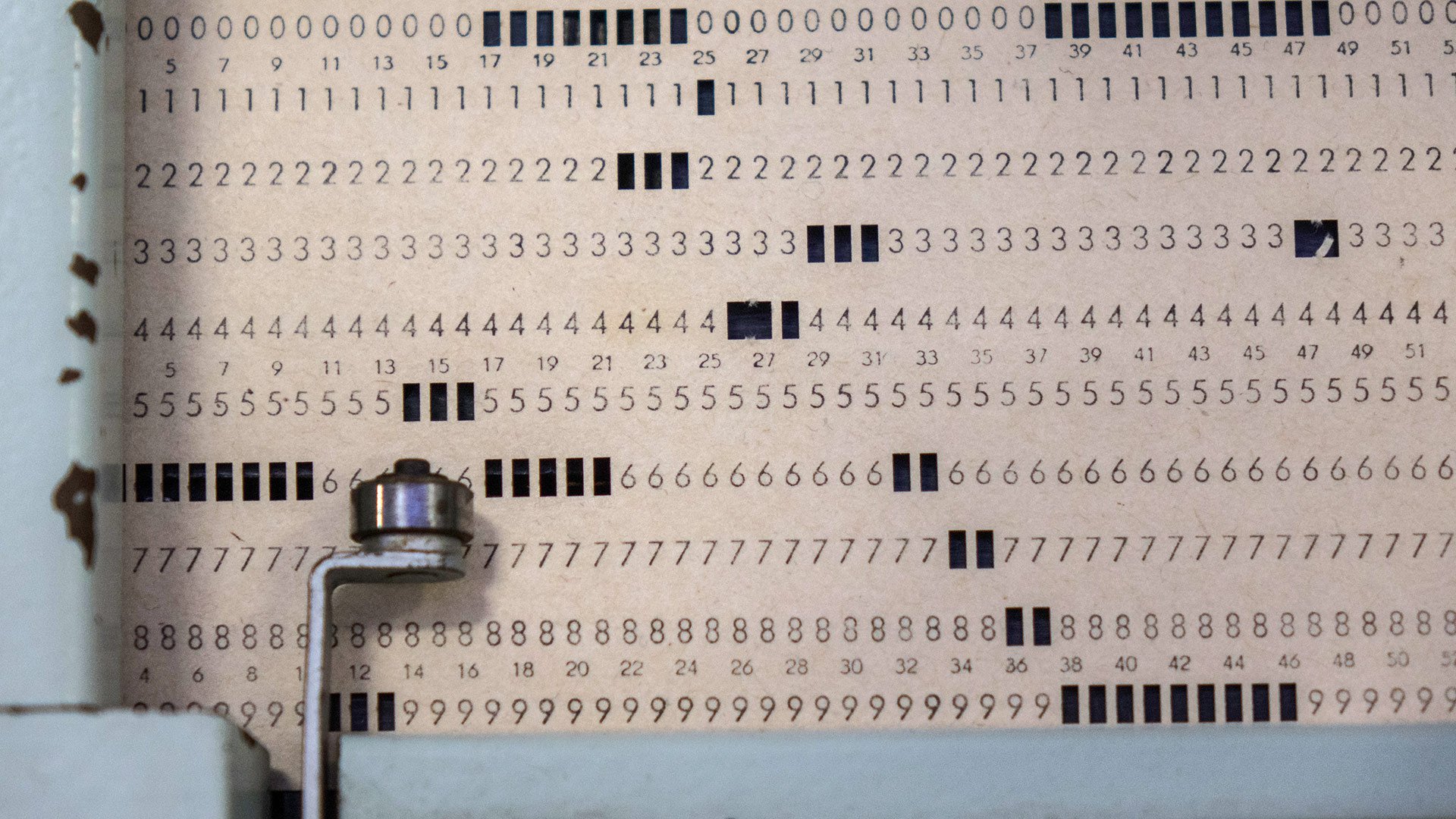

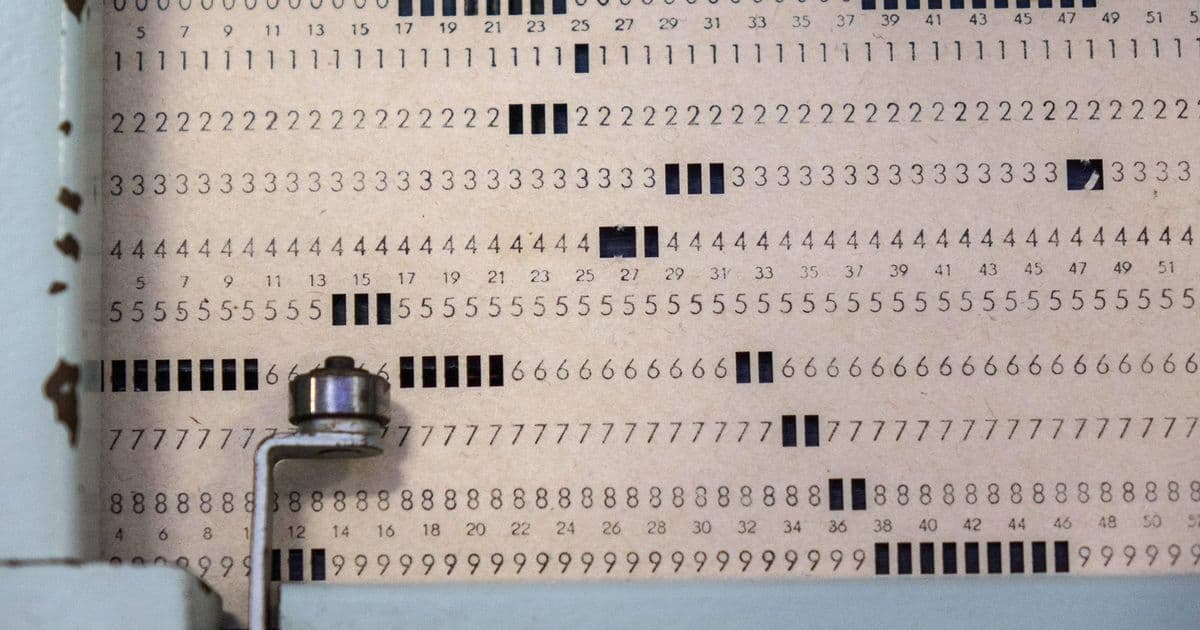

Caption: Punched card data storage (Image credit: Getty Images)

Caption: Punched card data storage (Image credit: Getty Images)

Central to the case were IBM-standard 80-column punch cards – the dominant data storage medium of the era. Each card represented a single line of code or data point, with complete programs requiring meticulously ordered stacks of hundreds or thousands of cards. This physicality made software theft straightforward: Stealing a program meant physically removing card decks. Yet investigators recognized that data also existed in intangible forms within system memory, prompting the warrant's unprecedented inclusion of electronic storage devices.

By 1971, magnetic tape and disk drives were supplementing punch cards for high-capacity storage. As detailed in Sergeant Terence Green's affidavit, investigators didn't merely confiscate hardware but generated printed directories of files and created magnetic tape copies to preserve evidentiary integrity. These actions established core forensic principles: isolating original media, creating verifiable duplicates, and documenting chain-of-custody procedures for volatile digital evidence.

Foundational Legal Precedents

The warrant's language revealed conceptual challenges in defining digital property. Terms like "memory bank" reflected attempts to map physical seizure protocols onto electronic environments – a struggle later documented in Jay Becker's Investigation of Computer Crime. Becker's manual, published through the National Center on White-Collar Crime, reproduced this warrant as a reference case and highlighted enduring dilemmas:

- Data Density: A single magnetic tape could hold information equivalent to "a shelf full of books," requiring translation into human-readable formats.

- Evidence Preservation: Becker emphasized duplicating storage media controls to prevent tampering, noting that "subsequent changes cannot compromise the evidentiary record."

- Overbreadth Concerns: Warrants required narrow scope because computers contained "an enormous amount" of unrelated data – foreshadowing modern debates about bulk data collection.

Lasting Technological and Legal Legacy

This 1971 case established procedural frameworks that evolved alongside storage technology. Punch cards gave way to floppy disks, hard drives, and cloud infrastructure, yet Becker's warnings about technical unfamiliarity and overbroad searches remain acutely relevant. Modern warrants routinely specify hash-verified disk images instead of physical hardware, and legal standards like the 2014 Riley v. California decision (requiring warrants for cellphone searches) echo the principle that digital data density demands heightened privacy protections.

As data storage scales from gigabytes to exabytes, the Santa Clara warrant's emphasis on targeted evidence collection and forensic integrity persists. With 90% of the world's data created in the last two years alone, these 55-year-old protocols continue shaping how legal systems balance investigative needs against the unique vulnerabilities of digital evidence.

Luke James is a freelance journalist covering the intersection of technology and legal frameworks.

Luke James is a freelance journalist covering the intersection of technology and legal frameworks.

Comments

Please log in or register to join the discussion