A deep dive into constructing an incremental query-based compiler and implementing a Language Server Protocol (LSP) server, demonstrating how the architecture enables responsive IDE features like diagnostics, goto definition, and autocomplete through a red-green algorithm for efficient recomputation.

The journey from a batch compiler to an interactive language server represents a fundamental shift in how we think about compilation. Traditional compilers operate as monolithic pipelines—parse, desugar, type-check, lower, optimize—each pass consuming the entire output of the previous stage. This approach works for command-line tools but fails spectacularly when we need interactive feedback, like the instant red squiggles that appear as you type in a modern IDE.

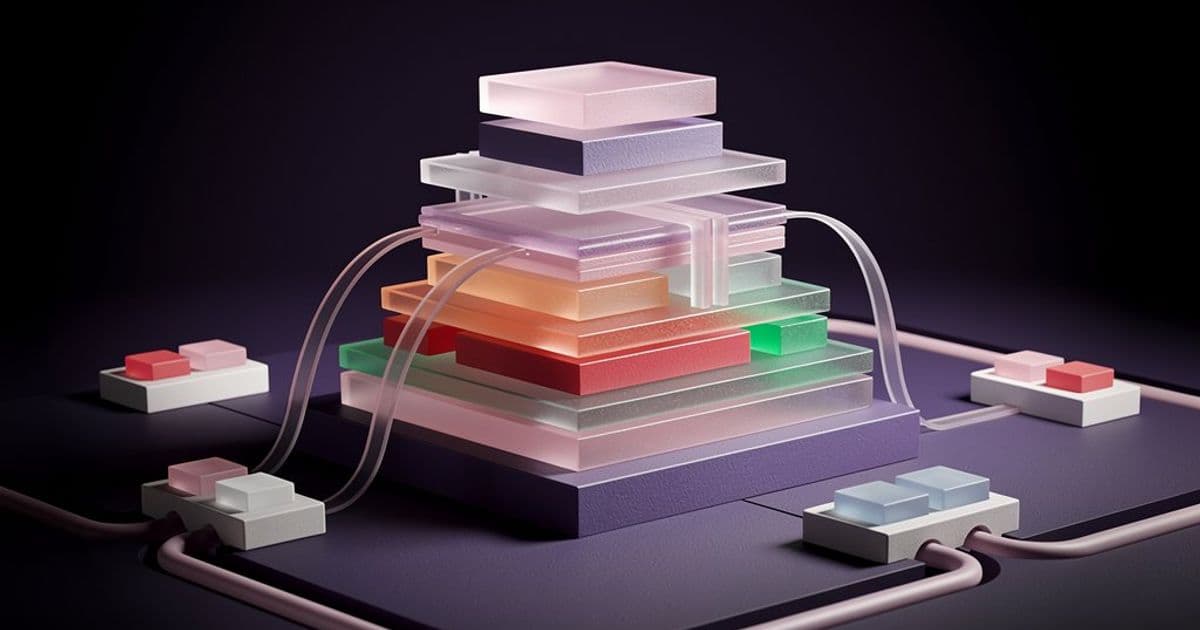

The solution lies in restructuring compilation as a series of interdependent queries rather than a linear pipeline. This query-based model, exemplified by rustc's architecture and formalized through algorithms like the red-green algorithm, transforms compilation from a batch process into an incremental, cacheable system. Each query represents a pure function that computes a specific piece of information—like the concrete syntax tree (CST) for a file, the type of a variable, or the WebAssembly output—while tracking its dependencies. When source code changes, only queries that depend on the modified portions need recomputation.

This architecture proves particularly powerful when paired with the Language Server Protocol (LSP). LSP solves the combinatorial explosion of editor-language integrations by introducing a unifying middleman: each language implements one server, each editor implements one client. The server answers requests for IDE features—hover information, goto definition, autocomplete—by querying the compiler incrementally. The result is responsive, interactive development that feels instantaneous even as the underlying compilation work is substantial.

The Query Engine: Foundation of Incremental Compilation

At the heart of this system lies the query engine, responsible for executing queries, caching results, and tracking dependencies. The engine's core insight is that queries form a directed acyclic graph (DAG), where each node represents a computation and edges represent dependencies. This structure enables the red-green algorithm, where queries are colored red (needs recomputation) or green (cached value is valid).

The algorithm works as follows: when a query is requested, the engine first checks its dependencies. If all dependencies are green, the query can use its cached value without execution. If any dependency is red, the query must recompute. Upon recomputation, the engine compares the new value with the cached one. If they're equal, the query remains green; if different, it becomes red, triggering recomputation of dependent queries.

Consider a simple example: changing whitespace in a source file. The content_of query (our sole input query) becomes red, triggering recomputation of cst_of (parsing). However, the CST remains identical, so cst_of stays green. Any queries depending on cst_of—like desugar_of or types_of—can reuse their cached values, skipping massive amounts of work.

The query engine implementation uses several key data structures:

- QueryKey: An enum identifying each query and its arguments. For example,

CstOf(Uri)represents parsing a specific file. - Database: Stores caches for each query type using concurrent hashmaps (

DashMap), plus a color map tracking query states and a revision counter for cache invalidation. - Dependency Graph: A DAG tracking which queries depend on which others, built dynamically as queries execute.

The query method orchestrates everything. It takes a query key, a cache reference, and a producer function. The producer contains the actual computation logic. The engine wraps this with dependency tracking and caching logic, implementing the red-green algorithm transparently.

From Compiler Passes to LSP Features

With the query engine in place, compiler passes become straightforward wrappers. Each pass—parsing, desugaring, name resolution, type inference, lowering—becomes a query that calls its underlying implementation and caches the result. The pattern is consistent:

- Add a variant to

QueryKeyfor the pass - Add a cache field to

Database - Implement the query method, calling the underlying pass function

For example, cst_of queries the content_of input query, passes the result to the parser, and caches the CST and any errors. Subsequent queries like desugar_of depend on cst_of, creating a chain of dependencies.

This architecture shines when implementing LSP features. Each feature becomes a query that composes existing compiler queries. Let's examine the key features:

Diagnostics

Diagnostics are the red squiggles that indicate errors. The diagnostics_of query collects errors from all frontend passes (parsing, name resolution, type checking) and converts them to LSP's Diagnostic format. The conversion requires mapping byte ranges to line/column positions, which newlines_of provides by building a byte-to-line mapping.

The LSP server implements did_open and did_change notifications to update the content_of query, triggering recomputation of diagnostics. The server then pushes diagnostics to the client via publish_diagnostics, providing immediate feedback.

Goto Definition

Goto definition jumps from a variable use to its definition. The definition_of query uses the core pair: syntax_node_starting_at and ast_node_of.

syntax_node_starting_at converts a line/column position to a CST node. It uses the parser's token_at_offset method to find the token at the cursor position, then walks up to the parent node. The implementation includes heuristics to bias toward identifiers and away from whitespace, since semantic features primarily operate on identifiers.

ast_node_of maps the CST node to an AST node by looking up the NodeId in the desugared AST's ast_to_cst mapping, then finding the corresponding node in the typed AST.

With the AST node in hand, definition_of walks the name-resolved AST to find the binding site (a Fun node or LetBinder), converts it back to a CST node, and returns its line/column range.

Hover

Hover shows type information when mousing over identifiers. The hover_of query follows a similar pattern: locate the syntax node, convert to AST node, extract the type, and format it for display.

The implementation includes special handling for function parameters (FunBinder), where we need to walk to the parent Fun node to get the type. The hover response includes a range where the tooltip should appear, ensuring it highlights the correct identifier.

References and Rename

References find all occurrences of a variable. The references_of query uses the name-resolved AST's var_reference method, which performs a depth-first search to find all nodes mentioning the variable. Each reference is converted to a location by mapping back through the AST-to-CST mapping.

Rename leverages the same references_of query but transforms the results into a WorkspaceEdit—a JSON structure telling the client to replace text at specific ranges with the new name. The server never modifies files directly; it provides instructions for the client to apply.

Autocomplete

Autocomplete is the most complex feature implemented. The completion_of query first calls scope_at to determine which variables are in scope at the cursor position.

scope_at builds a scope by walking the AST parents of the current node, collecting function bindings. It uses a zipped AST containing both human-readable names and typed information. Bindings are collected in reverse order to respect shadowing rules—later bindings in the walk shadow earlier ones.

The completion items are constructed from this scope, showing variable names and their types. The implementation focuses on identifiers in scope, leaving more sophisticated type-directed completion for future work.

Architecture Trade-offs and Implementation Details

The implementation makes several deliberate choices:

Simplicity over sophistication: The query engine is intentionally basic. It lacks cycle detection, cache persistence, and garbage collection—features present in production systems like rustc's query engine or the salsa framework. The author notes that once you understand the fundamentals, off-the-shelf solutions like salsa are preferable for real projects.

Concurrent data structures: Using DashMap for caches enables safe concurrent access, essential for an LSP server handling multiple asynchronous requests. The dependency graph uses RwLock for similar reasons.

Explicit dependency tracking: The QueryContext struct tracks the current query's parent via an Option<QueryKey> field. When a query executes another, it records the dependency in the graph. This explicit tracking enables the red-green algorithm to determine which queries need recomputation.

Minimal LSP protocol coverage: The server implements only a subset of LSP features. The tower-lsp crate handles the protocol details—HTTP headers, JSON marshaling, IO—allowing focus on the compiler integration. The implemented features (diagnostics, goto definition, hover, references, rename, autocomplete) cover the core IDE experience.

Error handling strategy: The compiler gracefully handles errors by returning Option types for later passes. If type inference fails, subsequent queries return None, preventing crashes while still providing partial information for features like syntax highlighting.

The Interactive Playground

The article references an interactive playground that demonstrates all implemented features. This playground serves as both a demonstration and a development tool, showing:

- The source code and all intermediate compiler representations (CST, desugared AST, typed AST, IR, WebAssembly)

- Live LSP request/response logs

- Execution output for runnable code

The playground validates the incremental nature of the query engine—changes to the source code trigger selective recomputation, visible in the timing of queries.

Broader Implications and Future Directions

This implementation illustrates a general pattern for building responsive developer tools. The query-based architecture isn't limited to compilers; it applies to any system where:

- Computations are pure functions of inputs

- Results need to be cached and reused

- Incremental updates are essential for responsiveness

The author notes potential applications in UI frameworks, game state management, and ETL pipelines. The core insight is separating computation from caching and dependency tracking.

For language development, this architecture enables sophisticated IDE features without rewriting logic for each editor. The LSP server becomes the single point of integration, providing features like:

- Semantic syntax highlighting

- Real-time error reporting

- Code navigation (goto definition, find references)

- Refactoring support (rename)

- Intelligent code completion

Future extensions could include:

- Type-directed completion: Using type information to filter completion candidates

- Method completion: For object-oriented or record-based systems

- Import suggestions: Automatically suggesting imports for undefined identifiers

- Code actions: Refactoring operations like extract method or inline variable

- Persistent caches: Storing query results to disk for faster startup

- Cross-file analysis: Extending the dependency graph across multiple files

Conclusion

Building an LSP server from a query-based compiler demonstrates how modern compiler architecture enables rich, interactive development experiences. The red-green algorithm provides a principled approach to incremental computation, while the LSP protocol offers a standardized interface for editor integration.

The implementation, while simplified, captures the essential ideas: pure computations, explicit dependency tracking, and cache-aware execution. For developers building new languages or tools, this pattern offers a path to responsive, IDE-quality feedback without the combinatorial explosion of editor-specific implementations.

The author's journey—from type inference to a complete compiler with LSP—highlights how focused, incremental development can lead to sophisticated systems. The interactive playground serves as both a testament to the work and an invitation to explore the ideas further.

For those interested in diving deeper, the full source code provides a working implementation, and the tower-lsp and salsa crates offer production-ready foundations for similar projects.

The key takeaway is that incremental compilation isn't just an optimization—it's a fundamental rethinking of how compilers interact with developers. By treating compilation as a series of queries rather than a monolithic pipeline, we enable tools that feel alive, responsive, and deeply integrated with our development workflow.

Comments

Please log in or register to join the discussion