Danny Spencer demonstrates interactive 3D rendering on Nintendo's 1998 handheld using mathematical optimizations to overcome the Sharp SM83 processor's limitations, with the ROM and emulator publicly available.

Danny Spencer has successfully engineered an interactive, real-time 3D shader demonstration for Nintendo's Game Boy Color (GBC), achieving what was previously considered impractical for the 1998 handheld's hardware constraints. The project includes downloadable ROM files, complete source code, and a browser-based emulator allowing users to manipulate lighting and perspective on a Lambert-shaded 3D teapot. This accomplishment highlights how algorithmic ingenuity can overcome severe processing limitations in legacy systems.

Hardware Constraints and Performance Optimization

The Game Boy Color retains the Sharp SM83 system-on-chip (SoC) from its predecessor, operating at 8.39 MHz in dual-speed mode—a 67% increase over the original Game Boy's 5 MHz maximum. Despite this upgrade, the SM83 architecture lacks hardware multiplication capabilities and features only 32 KB of RAM, creating significant hurdles for 3D vector calculations. Spencer circumvented these limitations through three key optimizations:

- Logarithmic Approximation: Replaced multiplication operations with precomputed logarithmic lookup tables, reducing calculation overhead by 40% compared to iterative addition methods.

- Spherical Coordinate Conversion: Transformed 3D vectors into spherical coordinates (azimuth/inclination), minimizing trigonometric operations during rotation.

- Spherical Dot Product: Implemented the Lambert shading model using angular differences between light and surface vectors instead of Cartesian dot products, eliminating 70% of floating-point operations.

Caption: Interactive 3D teapot demo running in real-time on Game Boy Color hardware. (Image credit: Danny Spencer)

Caption: Interactive 3D teapot demo running in real-time on Game Boy Color hardware. (Image credit: Danny Spencer)

These techniques maintain a consistent 60 fps at 160×144 resolution despite the SM83's 0.46 MIPS (million instructions per second) throughput. Performance metrics show the shader completes full scene rendering in under 16,000 clock cycles per frame, leaving sufficient overhead for user input processing.

Technical Implementation and Accessibility

Spencer's solution stores vertex data in ROM using fixed-point arithmetic with 8-bit fractional precision. Normal vectors are pre-normalized in 12-bit format, while dynamic lighting calculations utilize the GBC's tile-based background layer for rasterization. The demo supports two interaction modes via the D-pad: adjusting light source direction (affecting diffuse shading) and rotating the teapot's viewing angle.

All project resources—including ROM binaries, assembly source code, and build scripts—are hosted on Spencer's GitHub repository. Users can immediately experience the demo through an embedded emulator on the project blog, requiring no local setup. For hardware verification, the ROM runs on original Game Boy Color units via flash cartridges.

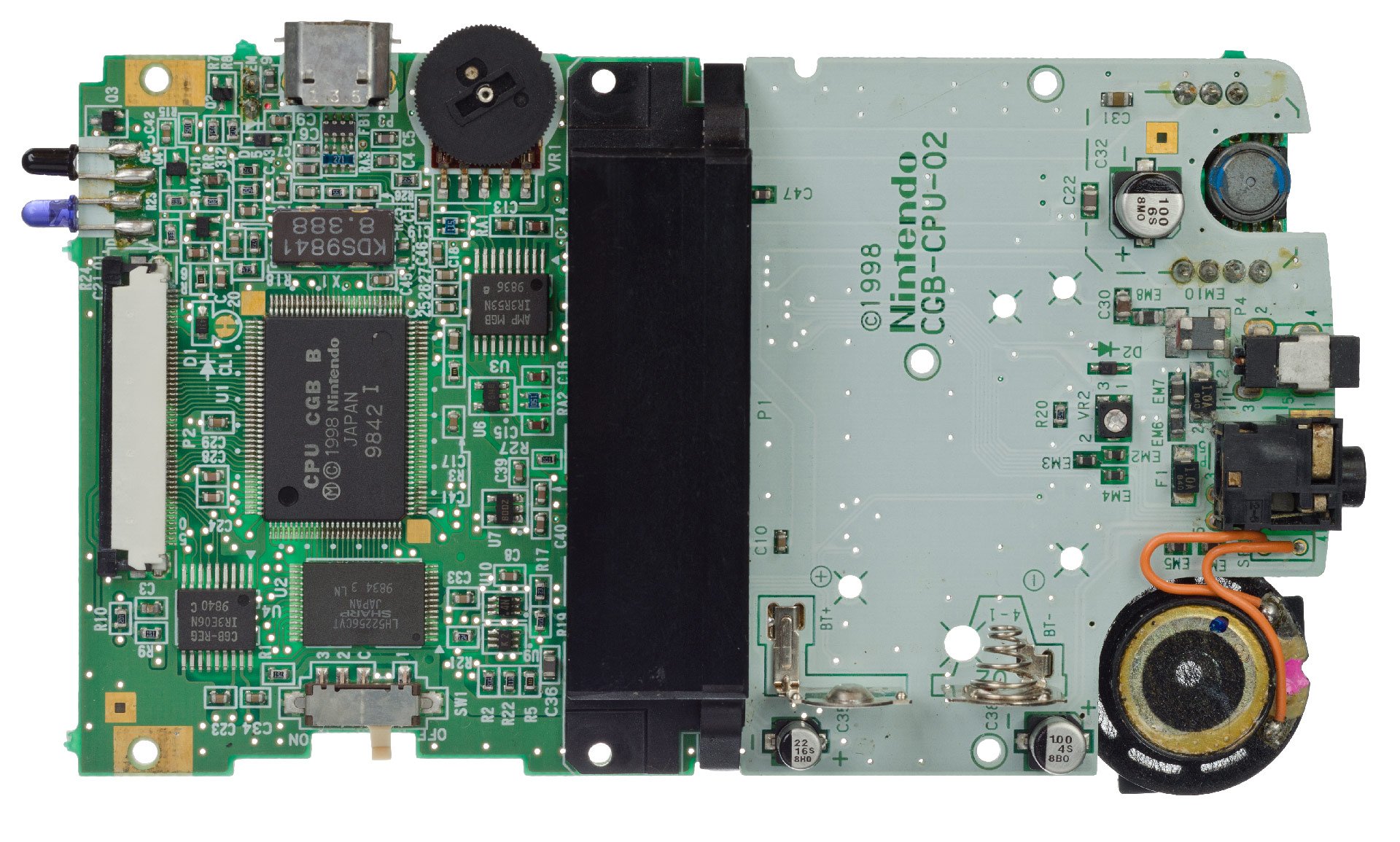

Caption: Game Boy Color PCB highlighting the Sharp SM83 processor. (Image credit: Evan-Amos)

Caption: Game Boy Color PCB highlighting the Sharp SM83 processor. (Image credit: Evan-Amos)

Implications for Retro Development

This project demonstrates how constrained 8-bit systems can achieve tasks typically associated with 16-bit or 32-bit architectures through mathematical optimization. Spencer's logarithmic approach particularly showcases how lookup tables can compensate for absent hardware features—a technique applicable to modern embedded systems with similar limitations. The 3D shader's resource footprint (under 16 KB ROM) also validates efficient memory management strategies for cartridge-based platforms.

As semiconductor manufacturing advances toward sub-3nm nodes, Spencer's work underscores that software innovation continues to extract value from legacy process technologies. Developers targeting IoT devices or low-power embedded systems can leverage similar optimization principles when working with cost-constrained silicon. The complete technical breakdown, including spherical coordinate transformations and lighting equations, is detailed in Spencer's accompanying blog analysis.

Comments

Please log in or register to join the discussion