Brian Potter examines the popular theory that renewable energy technologies will inevitably become cheaper than fossil fuel commodities, finding that while the distinction has some merit, the reality is far more complex with significant overlap between the two categories.

The debate over renewable energy's future often hinges on a compelling narrative: that wind and solar power, as manufactured technologies, will inevitably become cheaper through learning curves and economies of scale, while fossil fuels, as extracted commodities, face depletion and cartel control that prevent similar price declines. This "technologies vs. commodities" theory has gained significant traction in energy policy circles, but as Brian Potter carefully examines, the reality proves far more nuanced.

The Rocky Mountain Institute and other advocates argue that this distinction is fundamental to understanding the energy transition. Technologies, they contend, benefit from learning curves where costs fall predictably with cumulative production, while commodities face inherent limitations that prevent similar improvements. The theory suggests that as we build more wind turbines and solar panels, their costs will continue to fall exponentially, creating an unstoppable economic advantage over fossil fuels.

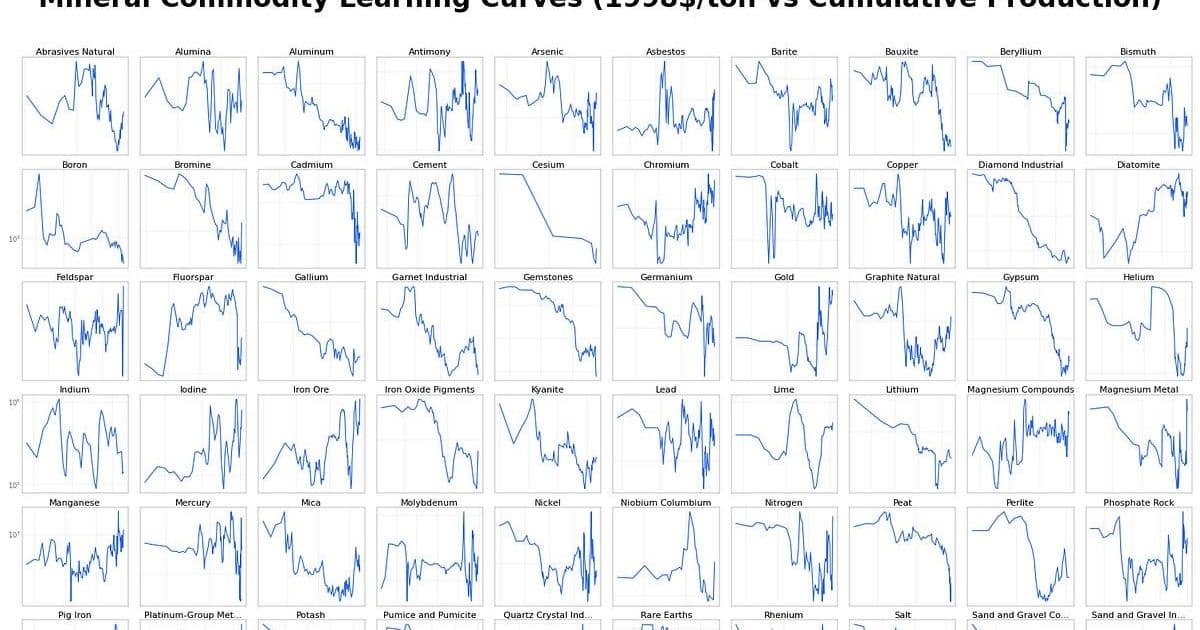

However, Potter identifies several problems with this binary framing. First, the historical evidence shows that commodities can and do get cheaper over time. Agricultural commodities have generally declined in price over the long term, and even fossil fuels experienced price declines for extended periods. Coal-generated electricity, for instance, fell by roughly a factor of ten over seventy years through technological improvements in plant efficiency, even though the coal itself remained a commodity input.

The price dynamics of technologies and commodities also show significant overlap. Both can benefit from technological process improvements that increase efficiency and reduce costs. The development of hydraulic fracturing dramatically improved oil and gas extraction efficiency, while innovations like the Bessemer process for steel and the Hall-Héroult process for aluminum led to substantial price declines in those commodities. Conversely, technologies face their own diseconomies of scale - wind power must contend with the best sites being developed first and wake effects from adjacent turbines reducing efficiency, while solar and wind installations increasingly face local opposition that can slow deployment.

Perhaps most importantly, Potter demonstrates that determining whether commodities follow learning curves is methodologically challenging. Many commodity datasets begin well after production started, missing centuries or even millennia of cumulative production. This creates a systematic bias that makes learning curves appear flatter than they actually are. For commodities where we have good data on total cumulative production - like titanium metal and aluminum after the Hall-Héroult process - the learning curve relationship becomes much clearer.

The implications of this analysis are significant for energy policy and investment decisions. While the technologies vs. commodities framework captures some real differences - manufactured goods do seem more consistently to decline in price, and technologies may be somewhat less subject to depletion dynamics - it oversimplifies a complex reality. The boundaries between these categories are fuzzy, and both face similar challenges of efficiency improvements, scale economies, and deployment constraints.

Rather than relying on this binary distinction, Potter suggests that policymakers and analysts would be better served by examining the specific dynamics at work for each energy source. Hydropower, for instance, doesn't fit neatly into either category - it's not commodity-based but also doesn't consist of modular, repetitively manufactured components like wind and solar. Similarly, the future cost trajectories of different energy sources will depend on specific technological developments, resource constraints, and social acceptance factors rather than broad categorical distinctions.

The philosophical irritation Potter expresses about the framework - that every aspect of civilization is ultimately a product of technology, including commodities like steel, oil, and corn - points to a deeper issue. The technologies vs. commodities distinction may be more useful as a heuristic for understanding certain dynamics than as a fundamental organizing principle for energy economics. As the energy transition accelerates, success will likely depend more on solving specific technical and social challenges than on relying on broad theoretical frameworks about the inevitable superiority of one category over another.

This nuanced analysis suggests that while renewable energy technologies do have advantages that could lead to continued cost declines, their future competitiveness will depend on addressing real-world constraints rather than simply benefiting from their status as "technologies." The energy transition will likely succeed or fail based on specific technological breakthroughs, policy choices, and social acceptance rather than on the abstract superiority of manufactured goods over extracted resources.

Comments

Please log in or register to join the discussion