The IBM 9020 was a pioneering fault-tolerant computer system built for the FAA's enroute air traffic control in the late 1960s, representing a fascinating intersection of military-derived technology, early multiprocessing concepts, and the unique demands of real-time safety-critical systems.

The story of the IBM 9020 begins not with civilian aviation, but with the Cold War military complex. The System for Air Defense (SAGE), developed by MIT's Lincoln Laboratory, was a monumental achievement in real-time computing, designed to coordinate radar data and guide interceptors against Soviet bombers. While SAGE is often mistakenly cited as an air traffic control system, its actual purpose was military ground-controlled interception. However, the technical overlap was significant: both applications required correlating aircraft identities with radar targets. This commonality led the Federal Aviation Agency (FAA) to launch the SATIN project in 1959, an initiative to adapt SAGE for civilian air traffic control.

SAGE, however, lacked critical safety functions essential for civilian airspace. It did not monitor altitude reservations, detect loss of separation between aircraft, or integrate instrument procedures and terminal information. The mid-century surge in air traffic made mid-air collisions a growing political and safety concern—problems SAGE was never designed to address. Concurrently, the Air Force pursued its own SAGE enhancement program, the Super Combat Center (SCC), which aimed to replace the massive, power-hungry vacuum-tube SAGE computers with transistorized systems housed in hardened underground bunkers. The SCC program was so ambitious that the Air Force suspended original SAGE installations, including one planned for Albuquerque, expecting the new design to immediately obsolete it. The FAA's SATIN project became subsumed into this broader SCC development effort.

The late 1950s saw a shift in Cold War priorities and national budget constraints. By 1960, the SCC program was largely canceled, and with it, the FAA's entire plan for computerized ATC using SAGE technology. The agency was left with a patchwork of custom software on commodity computers at various Air Route Traffic Control Centers (ARTCCs), many of which remained completely manual. The situation grew more urgent following the 1961 Beacon Report, which highlighted an immediate need for centralized, automated air traffic control amid rising collision risks and congressional scrutiny.

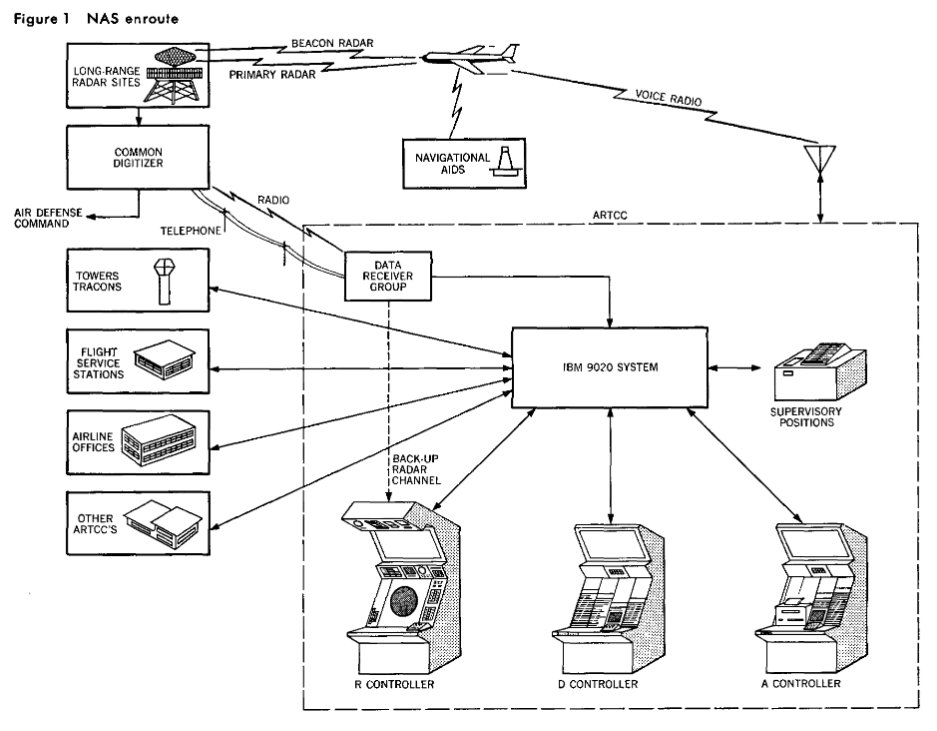

The formation of the Department of Transportation in 1967 brought a clear imperative: modernize the National Airspace System (NAS). The first step was NAS Enroute Stage A, designed to automate high-altitude enroute control. The FAA, having learned from past experiences, contracted directly with IBM, bypassing intermediaries. The result was the IBM 9020—a system that embodied both cutting-edge computer architecture and the pragmatic, sometimes duct-tape-like, engineering of the era.

A Multisystem Architecture

The 9020 was built on the foundation of IBM's System/360, introduced in 1965. The S/360 was a landmark in computer history, offering a unified architecture across a family of solid-state, microcoded machines. A key figure in its development was Gene Amdahl, whose work on multiprocessing systems led to the concept of the "multisystem"—a cluster of independent computers operating as a single entity. While modern readers might see echoes of distributed computing or multiprocessing, the 1960s were a nascent era for computer-to-computer communication. The 9020 multisystem was both prescient and distinctly of its time, combining ideas like atomic resource locking with hardware assignments that dedicated CPUs to specific tasks.

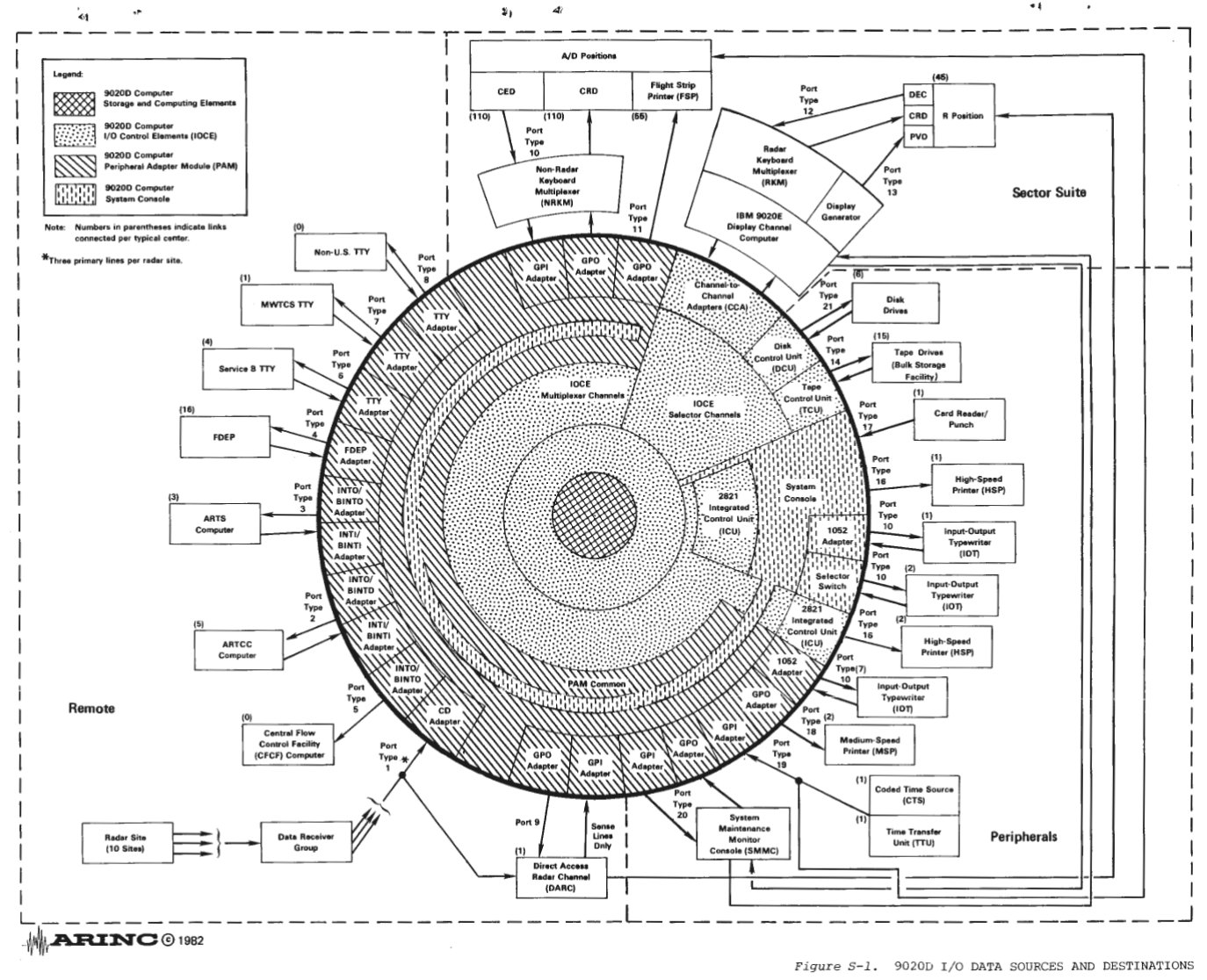

The 9020's architecture was a marvel of fault tolerance and dynamic resource allocation. A typical system comprised six to seven S/360 computers connected via a common address and memory bus. These were divided into two pools: Compute Elements (CEs) for running application software and I/O Control Elements (IOCEs) for managing peripherals. Supporting them were up to ten Storage Elements—specialized memory controllers with features for locking, prioritization, and diagnostics. Each Storage Element provided either 131 KB or about 1 MB of memory, with a maximum system capacity of approximately 3.4 MB (not all usable simultaneously due to redundancy).

The system was designed for 50% redundancy during peak traffic. A typical configuration included three CEs and three IOCEs, allowing the full ATC workload to run on just two of each. The remaining elements could remain in standby, ready to automatically take over if a failure occurred. This redundancy was critical for meeting the FAA's stringent reliability requirements. Elements could also be temporarily removed from the multisystem and operated in "S/360 compatibility mode"—effectively standalone machines—for training or diagnostic purposes. For example, one CE and one IOCE could be partitioned to run training scenarios using recorded data, simulating a complete second 9020.

The System Console and Control Philosophy

One of the most unique features of the 9020 was its System Console. While individual S/360 machines had their own operator consoles, the 9020's System Console served as a unified interface for the entire multisystem. A single operator could monitor all components, interact with any element via a teletypewriter, and manually troubleshoot the shared storage bus. When operating as part of the multisystem, the individual S/360 consoles were disabled, centralizing control and simplifying operations.

The System Console was also the gateway for system reconfiguration. Operators could manually reconfigure the system—for testing, training, or maintenance—by triggering interrupts that initiated the Operational Error Analysis Program (OEAP). This program was the heart of the 9020's self-management and fault recovery.

The Operational Error Analysis Program (OEAP)

The 9020's software was divided into a "supervisor state" (analogous to a modern kernel) and a "problem state" (user space). The Control Program, a reentrant scheduler, ran in the supervisor state and managed task execution across the multisystem. It used interrupts extensively to handle the demands of real-time processing and peripheral management. The Control Program's timing analysis feature recorded task start times and durations to tape, enabling engineers to analyze performance and determine load limits—essentially early distributed tracing.

When errors occurred—whether from hardware interrupts (like power loss or high temperature) or software timeouts—the Control Program would hand execution to the OEAP. The OEAP was a sophisticated diagnostic and recovery engine. It began by performing self-diagnosis, reading error registers and gathering data from other machines and storage elements. Based on the diagnosis, it could take various actions:

- For transient errors (e.g., a failed I/O operation due to a network glitch), it might increment counters, update task states, and allow the Control Program to retry.

- For solid hardware failures, it would reconfigure the system by rewriting configuration registers, removing the failed element from service, and bringing a standby element online.

The OEAP's recovery process was designed to complete within 30 seconds. In the case of a power loss, each component had a 5.5-second battery backup—enough time for the OEAP to stabilize the system state. If the primary OEAP failed to complete, other machines would start their own OEAP instances in "time-down" mode, waiting a random interval before taking over if the original remained incomplete. This decentralized approach ensured that even with multiple failures, the system could eventually diagnose and recover.

The Air Traffic Control Application

The 9020's application software was organized into five modules: Input Processing, Flight Processing, Radar Processing, Output Processing, and Liaison Management. These modules operated asynchronously, handling data from a vast array of peripherals.

Controllers at each ARTCC worked in sectors, typically staffed by three personnel: the R controller (radar monitoring), the D controller (flight plan management), and the A controller (general assistance). Their consoles featured a 22" CRT plan-view radar display (PVD), a computer readout device (CRD) for text output, and a computer entry device (CED) for keyboard input. Flight strips—paper records of flight clearances—were automatically printed by teleprinters.

The 9020's role extended beyond the ARTCC. Teletypewriter circuits connected control towers, terminal radar facilities, airline dispatch offices, and flight service stations, allowing flight plans to be entered and updated before aircraft reached enroute control. High-speed leased lines linked neighboring 9020 systems, enabling seamless handoffs between ARTCCs.

The original NAS Stage A architecture separated the radar display function from the central computing complex. The 9020 handled data processing, while Raytheon's 730 Display Channel converted digital data into drawing instructions for the PVDs. Some ARTCCs later installed a second 9020 as the Display Channel Complex (DCC) to improve uptime. The DCC remained in service until the 1990s, outliving the main 9020 CCCs.

Legacy and Evolution

The 9020's service life was notable. While SAGE operated from 1958 to 1984, the 9020, though younger, outlived it by only a few years. In 1986, the FAA began replacing the 9020 CCCs with the HOST system, based on the IBM 3083. However, the 9020 DCCs continued controlling PVDs until the ERAM Stage A project in the 1990s. A single reduced-size 9020 system was sold to the UK Civil Aviation Authority and operated until 1990.

The 9020 represents a pivotal moment in the history of real-time computing. It bridged the gap between military-derived systems like SAGE and modern air traffic control automation, pioneering concepts of fault tolerance, multisystem architecture, and centralized control that remain relevant today. Its design reflects both the optimism and the constraints of 1960s engineering—a sophisticated system built from commodity components, capable of managing the complex, safety-critical task of coordinating thousands of aircraft across the national airspace.

For further reading, IBM's documentation and papers in the IBM Systems Journal provide detailed technical insights into the 9020's architecture. The evolution of air traffic control systems continues, with the FAA's NextGen program representing the latest chapter in this ongoing story of technological adaptation and innovation.

Comments

Please log in or register to join the discussion