With Microsoft ending all support for Windows XP, users face a critical decision: stick with an insecure system, pay for expensive upgrades to newer Windows versions, or migrate to Linux. This guide examines the technical realities of each path, from hardware compatibility to application ecosystems, and explains why Linux offers a viable alternative for many XP holdouts.

Microsoft's final retirement of Windows XP on April 8, 2014 marks the end of an era. After multiple extensions driven by enterprise demand, the company has drawn a hard line: no more security patches, no technical support. Your XP machine will continue running, but it will become increasingly vulnerable to new exploits. The question facing millions of users isn't whether to change, but what direction to take.

The Windows Upgrade Path: Cost and Complexity

Upgrading to Windows 7 or 8.1 seems like the straightforward choice, but the reality involves multiple layers of expense and friction. First, hardware compatibility becomes a major barrier. A six-year-old XP machine likely lacks the processing power, RAM, and storage bandwidth that modern Windows releases demand. The newer operating systems are considerably heavier, and performance on aging hardware often proves unsatisfactory.

Even if the hardware supports it, application compatibility remains uncertain. Your existing Windows software may not function properly on newer versions, assuming you still possess the original installation media. Peripherals like scanners and printers frequently lose driver support across major Windows version jumps, forcing additional hardware purchases.

For users who buy new computers with Windows 8.1 pre-installed but dislike the interface, Microsoft offers a "downgrade" path—but calling it cumbersome understates the friction. Downgrading requires Windows 7 Professional (OEM version at $139, retail at $209), involves phoning Microsoft for activation permission, and comes with strict license limitations. Microsoft treats this as a temporary concession, expecting users to eventually accept the modern interface.

The Linux Alternative: Technical Freedom

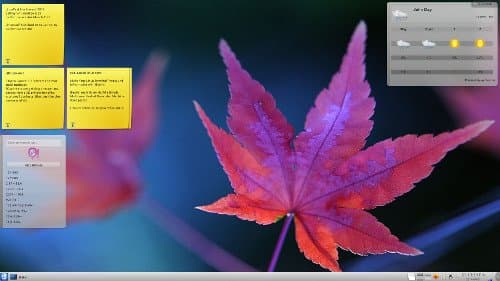

Linux presents a fundamentally different value proposition. As a mature, Unix-like operating system, it offers professional-grade reliability without the licensing overhead. Users can download distributions freely, test them via live USB or DVD without touching the hard drive, and install alongside existing XP systems for dual-boot flexibility.

The technical advantages are concrete:

Security Architecture: Linux's permission model and open-source development process make it inherently resistant to the malware ecosystem that targets Windows. The absence of a monoculture means viruses designed for Windows simply don't execute. This isn't marketing—it's a structural difference in how the operating system handles privileges and process isolation.

Hardware Efficiency: Linux distributions run effectively on hardware that would struggle with modern Windows. This isn't just about older machines; even contemporary budget hardware performs better because the OS isn't carrying decades of backward compatibility cruft.

Software Management: Package managers like APT (used by Debian/Ubuntu) or DNF (Fedora) provide centralized, cryptographically verified software installation. Compare this to Windows' scattered download-and-install model, where users hunt across vendor websites. Linux repositories contain thousands of applications, all vetted and maintained.

Licensing Freedom: No activation servers, no license tiers artificially crippling features, no "phoning home" for permission. You own your installation completely.

The Application Reality Check

Here's where the decision requires honest assessment. Windows applications don't run natively on Linux. Period. Outlook, Internet Explorer, and Microsoft Office won't execute. However, the landscape of cross-platform and equivalent software is extensive:

- Browsers: Firefox, Chrome, and Opera run identically across platforms

- Office Suites: LibreOffice provides robust document compatibility with MS Office formats

- Email: Thunderbird handles email and calendaring

- Finance: Moneydance and GnuCash replace Quicken/QuickBooks

- Creative Work: The GIMP, Inkscape, Krita, and Blender offer professional-grade alternatives

The key is inventorying your actual needs versus brand loyalty. Many users discover their "essential" Windows applications have Linux equivalents that match or exceed the originals. For true legacy Windows software needs, Linux offers virtualization solutions like VirtualBox, allowing you to run XP in a contained environment when necessary.

Distribution Selection: One Size Doesn't Fit All

Linux's diversity manifests in hundreds of distributions (distros), each optimized for different use cases:

Ubuntu Linux dominates beginner-friendly adoption with polished desktop environments and extensive documentation. Its commercial arm, Canonical, offers paid support options for users who want them.

Linux Mint builds on Ubuntu's foundation but provides a more traditional desktop experience, making it ideal for users transitioning from Windows XP's interface paradigm.

Fedora and openSUSE target technically advanced users who want bleeding-edge packages and are comfortable with more complex system administration.

Mageia offers a balanced approach suitable from beginner to advanced levels.

Hardware Considerations: Buying vs. Building

For users purchasing new systems, specialized Linux vendors like System76 and ZaReason engineer their hardware specifically for Linux compatibility. Unlike budget Windows PCs built to micro-cost constraints, these systems use reliable components and provide Linux-native support. This eliminates the driver hunting that plagues Windows installations.

The Myth of Windows "Ease of Use"

Microsoft's marketing successfully created the illusion that computers are inherently simple tools requiring no training. This is demonstrably false. Personal computers are sophisticated power tools, and Windows' complexity is often hidden rather than absent. The constant security patching, license management, and application compatibility issues represent ongoing cognitive overhead.

Linux, properly configured, is simpler to maintain. The update system handles the OS and all installed software simultaneously. Configuration is centralized and transparent. The learning curve exists, but it's a single curve rather than the recurring "Windows update broke my printer" surprises.

Android as a Middle Path

For users whose computing needs center on web browsing, media consumption, and basic productivity, Android tablets and laptops offer a touch-optimized Linux variant. Devices like the ZaTab provide open Android experiences without carrier lock-in. Android's expansion into traditional laptops creates another migration path that bridges mobile and desktop paradigms.

Making the Transition Work

The reality is that any OS migration involves learning and adjustment. Windows 7 differs significantly from XP. Windows 8.1 differs even more dramatically. Linux requires learning new workflows, but those workflows are often more logical and consistent than Windows' accumulated legacy decisions.

The investment in learning Linux pays dividends in reduced maintenance overhead, improved security, and genuine control over your computing environment. For the millions of XP users facing this decision, Linux isn't just a free alternative—it's often the superior technical choice.

Resources for Migration

- Ubuntu Linux - Primary distribution for beginners

- Linux Mint - Windows-like interface transition

- Fedora Linux - Cutting-edge features for advanced users

- openSUSE - Enterprise-grade stability

- Mageia Linux - Community-driven distribution

- System76 - Linux-native computer vendor

- ZaReason - Linux hardware specialist

- LibreOffice - Office suite alternative

- VirtualBox - Run legacy Windows apps in Linux

Comments

Please log in or register to join the discussion