Transactions are the fundamental building blocks that make SQL databases reliable, handling trillions of operations daily while ensuring data consistency even during failures or concurrent access.

Transactions are the invisible engine that powers every SQL database, executing trillions of operations every single day across thousands of applications. From your banking app to your favorite social media platform, database transactions work silently in the background, ensuring that every operation either completes fully or not at all.

What Exactly Is a Database Transaction?

A transaction is a sequence of actions that we want to perform on a database as a single, atomic operation. Think of it like a bank transfer: you want to withdraw money from one account AND deposit it into another. Both operations must succeed together, or neither should happen at all.

In MySQL and Postgres, we begin a new transaction with BEGIN; and end it with COMMIT;. Between these two commands, any number of SQL queries that search and manipulate data can be executed. The act of committing is what atomically applies all of the changes made by those SQL statements.

But what happens when things go wrong? Sometimes transactions don't commit due to unexpected events like hard drive failures or power outages. Databases like MySQL and Postgres are designed to handle these scenarios using disaster recovery techniques. Postgres, for example, uses its write-ahead log mechanism (WAL) to ensure data integrity even during system failures.

There are also times when we want to intentionally undo a partially-executed transaction. This happens when we encounter missing or unexpected data midway through, or get a cancellation request from a client. For this, databases support the ROLLBACK; command, which undoes all changes and leaves the database unaltered by that transaction.

Why Transactions Matter: Concurrency and Isolation

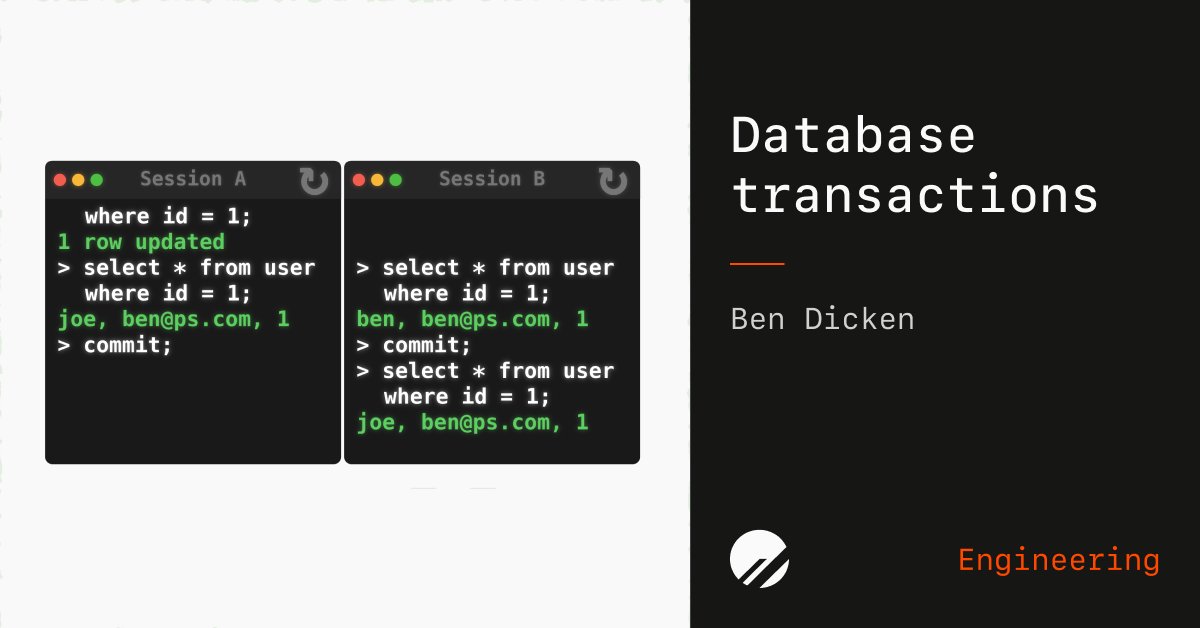

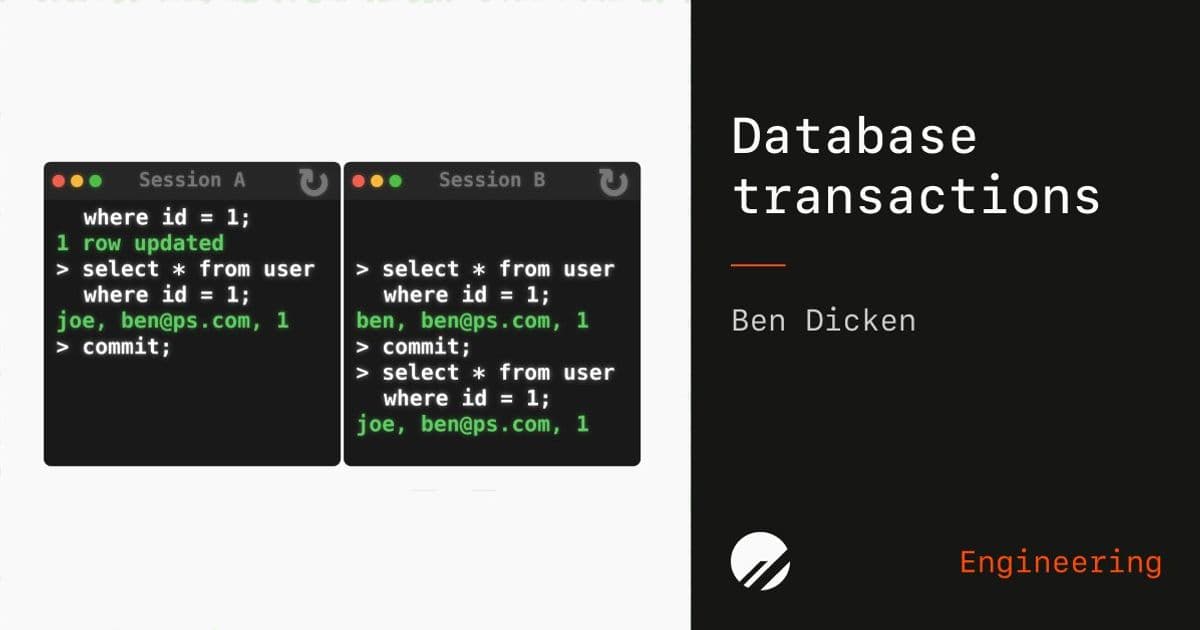

A key reason transactions are useful is to allow execution of many queries simultaneously without them interfering with each other. Consider two sessions connected to the same database: Session A starts a transaction, selects data, updates it, selects again, and then commits. Session B selects that same data twice during a transaction and again after both transactions have completed.

Session B does not see the name update from "ben" to "joe" until after Session A commits the transaction. This isolation is crucial for maintaining data consistency in multi-user environments.

Consistent Reads: Seeing What You Expect to See

During a transaction's execution, we want it to have a consistent view of the database. This means that even if another transaction simultaneously adds, removes, or updates information, our transaction should get its own isolated view of the data, unaffected by these external changes, until the transaction commits.

MySQL and Postgres both support this capability when operating in REPEATABLE READ mode (plus all stricter modes). However, they each take different approaches to achieving this same goal.

Postgres: Multi-Version Concurrency Control (MVCC)

Postgres handles consistent reads with multi-versioning of rows. Every time a row is inserted or updated, it creates a new row along with metadata to keep track of which transactions can access the new version.

Each row version has two important metadata fields:

xmin: The ID of the transaction that created this row versionxmax: The ID of the transaction that caused a replacement row to be created

Postgres uses these to determine which row version each transaction sees. When you have two sessions running simultaneously, before a commit, one session cannot see the other's modifications. After the commit, the changes become visible to all transactions.

But what happens to all those duplicated rows over time? Postgres uses the VACUUM FULL command to purge versions of rows that are no longer needed and compacts the table in the process, reclaiming unused space.

MySQL: Undo Logs

MySQL takes a different approach. Instead of keeping many copies of each row, MySQL immediately overwrites old row data with new row data when modified. This requires less maintenance over time but still needs the ability to show different versions of a row to different transactions.

For this, MySQL uses an undo log—a log of recently-made row modifications, allowing a transaction to reconstruct past versions on-the-fly. Each MySQL row has metadata columns that keep track of the ID of the transaction that updated the row most recently and a reference to the most recent modification in the undo log.

Isolation Levels: Balancing Safety and Performance

The idea of repeatable reads is important for databases, but this is just one of several isolation levels databases like MySQL and Postgres support. This setting determines how "protected" each transaction is from seeing data that other simultaneous transactions are modifying.

Both MySQL and Postgres have four levels of isolation, from strongest to weakest:

- Serializable: All transactions behave as if they were run in a well-defined sequential order

- Repeatable Read: Prevents non-repeatable reads and phantom reads (in Postgres)

- Read Committed: Prevents dirty reads but allows non-repeatable reads and phantom reads

- Read Uncommitted: Allows dirty reads, non-repeatable reads, and phantom reads

Stronger levels of isolation provide more protections from data inconsistency issues across transactions but come at the cost of worse performance in some scenarios.

Understanding the Phenomena

- Phantom Reads: A transaction runs the same SELECT multiple times but sees different results the second time around due to data inserted by other transactions

- Non-Repeatable Reads: A transaction reads a row, then later re-reads the same row, finding changes by another already-committed transaction

- Dirty Reads: A transaction sees data written by another transaction that is not yet committed

Handling Concurrent Writes: The Showdown

What if two transactions need to modify the same row at the same time? This is where MySQL and Postgres take fundamentally different approaches, especially in SERIALIZABLE mode.

MySQL: Row-Level Locking

MySQL handles conflicting writes with locks. A lock is a software mechanism for giving ownership of a piece of data to one transaction. When a transaction needs to "own" a row without interruption, it obtains a lock.

There are two main types of locks:

- Shared (S) locks: Can be obtained by multiple transactions on the same row simultaneously, typically used for reading

- Exclusive (X) locks: Can only be owned by one transaction for any given row at any given time, used for writing

In SERIALIZABLE mode, all transactions must obtain X locks when updating a row. When two transactions try to update the same row simultaneously, this can lead to deadlock. MySQL can detect deadlock and will kill one of the involved transactions to allow the other to make progress.

Postgres: Serializable Snapshot Isolation

Postgres handles write conflicts in SERIALIZABLE mode with less locking and avoids the deadlock issue completely. As transactions read and write rows, Postgres creates predicate locks, which are "locks" on sets of rows specified by a predicate.

Combined with multi-row versioning, this lets Postgres use optimistic conflict resolution. It never blocks transactions while waiting to acquire a lock but will kill a transaction if it detects that it's violating the SERIALIZABLE guarantees.

The Bigger Picture

Transactions are just one tiny corner of all the amazing engineering that goes into databases, but a fundamental understanding of what they are, how they work, and the guarantees of the four isolation levels is helpful for working with databases more effectively.

Whether you're building a simple CRUD application or a complex distributed system, understanding transactions helps you write more reliable code and make better architectural decisions. The next time you see a database commit or rollback, remember the sophisticated machinery working behind the scenes to keep your data consistent and your applications running smoothly.

Comments

Please log in or register to join the discussion