Steve Klabnik offers a framework for understanding Steve Yegge's controversial Gas Town project, arguing that its apparent opacity is a deliberate design choice to attract a specific community while challenging conventional software development assumptions.

The software development community has been grappling with Gas Town, Steve Yegge's recent project that has elicited reactions ranging from confusion to outright dismissal. The project, launched just under two weeks ago, has already attracted significant attention and contributions—over 100 pull requests from nearly 50 contributors, adding 44,000 lines of code. Yet many developers find themselves asking "what the fuck?!?" when encountering Yegge's posts about it. This reaction, while understandable, might be missing the point entirely.

Gas Town represents something both mundane and revolutionary: a workspace where AI agents autonomously tackle bug reports and feature requests from a project's tracker. At its core, this isn't particularly novel—humans have organized work through task lists for centuries. What makes Gas Town experimental is the shift from human workers to autonomous agents. This transition feels inevitable once you accept the premise that software agents can successfully complete programming tasks. Why wouldn't they organize work the same way humans do?

The project's architecture draws from proven patterns in distributed systems. Yegge employs Erlang's supervisor trees and mailbox concepts, creating a solid foundation for agent coordination. Erlang's legendary reliability in concurrent systems isn't accidental—it represents decades of hard-won knowledge about managing state and failures in distributed environments. By building on these patterns, Gas Town isn't reinventing the wheel; it's applying time-tested engineering principles to a radically new context.

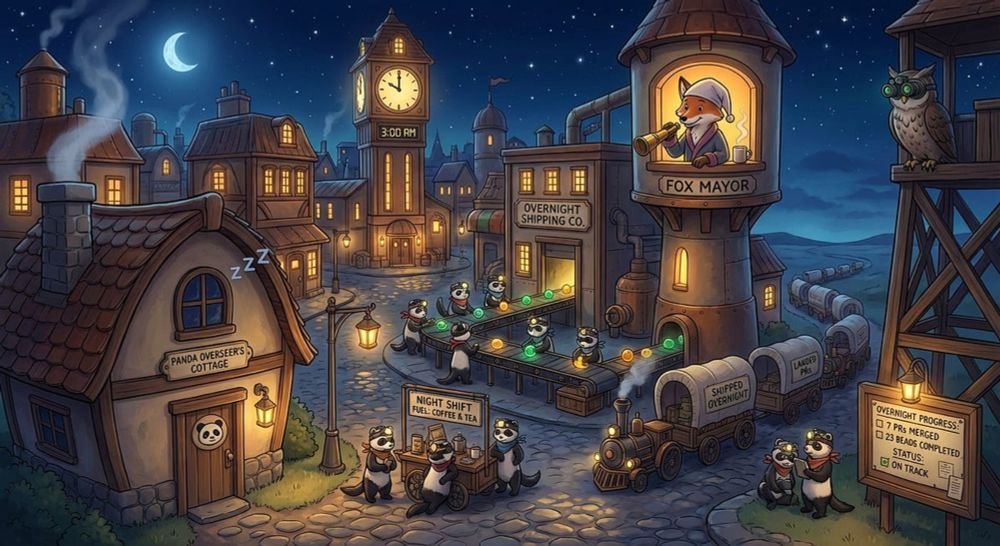

Yet the terminology surrounding Gas Town feels deliberately opaque. Terms like "Polecats" and "Refinery" create barriers to understanding that seem unnecessary for a technical project. This opacity isn't accidental—it's a strategic choice. When you're working on something genuinely new, conventional language often fails to capture the essence of what you're building. Yegge isn't just documenting a tool; he's attempting to communicate a new way of thinking about software development.

Consider the parallel with surrealist art. René Magritte's 1929 painting "La Trahison des images" depicts a pipe with the caption "Ceci n'est pas une pipe" (This is not a pipe). The work forces viewers to confront the distinction between representation and reality. Similarly, Gas Town's unusual terminology pushes developers to question fundamental assumptions about software development. When we say "bug tracker," we're already making assumptions about what bugs are, how they should be categorized, and who should fix them. Yegge's terminology forces us to examine these assumptions rather than accepting them as given.

This approach serves a dual purpose. First, it challenges entrenched thinking. The software development community has accumulated many sacred cows over decades—assumptions about testing, code review, deployment processes, and team organization. Some of these assumptions were solidified before AI agents existed as a practical tool. When the underlying technology changes fundamentally, it's worth re-examining whether our processes still make sense.

Second, unusual terminology acts as a filter. It attracts developers who are genuinely curious about rethinking software development from first principles while repelling those who prefer established patterns. This isn't gatekeeping for its own sake—it's a way to build a community of like-minded explorers who are willing to venture into uncertain territory together. When you know your work will attract attention, using conventional language might bring in everyone, but using distinctive terminology helps attract the right people.

The experimental nature of Gas Town becomes clearer when contrasted with more rigorous approaches to AI in software development. Oxide Computer Company, known for its engineering rigor, recently discussed how they use LLMs to build robust systems software rather than creating "vibe-coded" prototypes. Their approach emphasizes maintaining high standards even when incorporating AI tools. Gas Town, by contrast, appears to be aggressively non-rigorous in its current form. This isn't necessarily a flaw—it's a different experimental strategy.

When exploring fundamentally new territory, there's tension between rigor and exploration. Rigor ensures quality and reliability, but it can also constrain innovation. Gas Town's approach seems to prioritize learning what's possible over ensuring everything works perfectly from the start. This mirrors early aviation experiments where many pioneers died testing ideas that seemed promising but proved dangerous. The failures themselves provided crucial data about what doesn't work.

The question of what rigor means in an agent-driven development environment remains open. Is rigor synonymous with passing tests? Does it require complete upfront specification of system state? Or is rigor something we work toward incrementally? Gas Town's current experimental phase might help answer these questions by showing what happens when you remove traditional constraints and see what emerges.

For developers trying to understand AI's impact on their profession, 2026 represents a critical inflection point. The tools are changing, but more importantly, the fundamental assumptions about how software gets built are being questioned. Gas Town, whether it ultimately succeeds or fails, forces us to confront these questions. Some old assumptions might still hold true, while others may need to be discarded entirely.

The project's experimental nature means its ultimate value isn't just in what it produces, but in what it teaches us about the boundaries of what's possible. Like early rocket experiments that exploded on the launchpad, Gas Town might fail spectacularly. But each failure reveals something about the problem space. The 44,000 lines of code contributed in just 12 days represent not just working software, but collective learning about how to coordinate AI agents in real development workflows.

Whether you approach Gas Town with skepticism or curiosity, its existence marks a significant moment in software development history. It represents the first serious attempt to create a production-ready system where autonomous agents handle the bulk of development work. The terminology might seem strange, the approach might seem unorthodox, but the underlying question is profound: can we build software systems where AI agents are first-class participants in the development process?

The answer won't come from reading documentation or analyzing code. It will come from watching what happens when real developers try to use Gas Town for real projects. The community forming around it—whether they're contributing code, writing about it, or simply observing—represents the early adopters of what might become a fundamental shift in how software gets built. Their experiences, successes, and failures will provide the data needed to understand whether agent-driven development represents the future or merely an interesting experiment.

For now, Gas Town remains a question mark. But in software development, questions are often more valuable than answers. They push us to explore, experiment, and eventually, to build things we couldn't previously imagine. Whether Gas Town ultimately delivers on its promise or becomes a cautionary tale, it's already forcing the industry to think differently about fundamental questions of software development. And in that sense, it's already succeeding.

Comments

Please log in or register to join the discussion