SpaceX plans to lower the orbits of its entire current Starlink fleet from 550 km to 480 km by 2026, a move driven by solar cycle physics and a crowded low Earth orbit environment. The shift aims to reduce collision risks and ensure faster deorbiting of failed satellites, but it also highlights the growing operational challenges of managing megaconstellations.

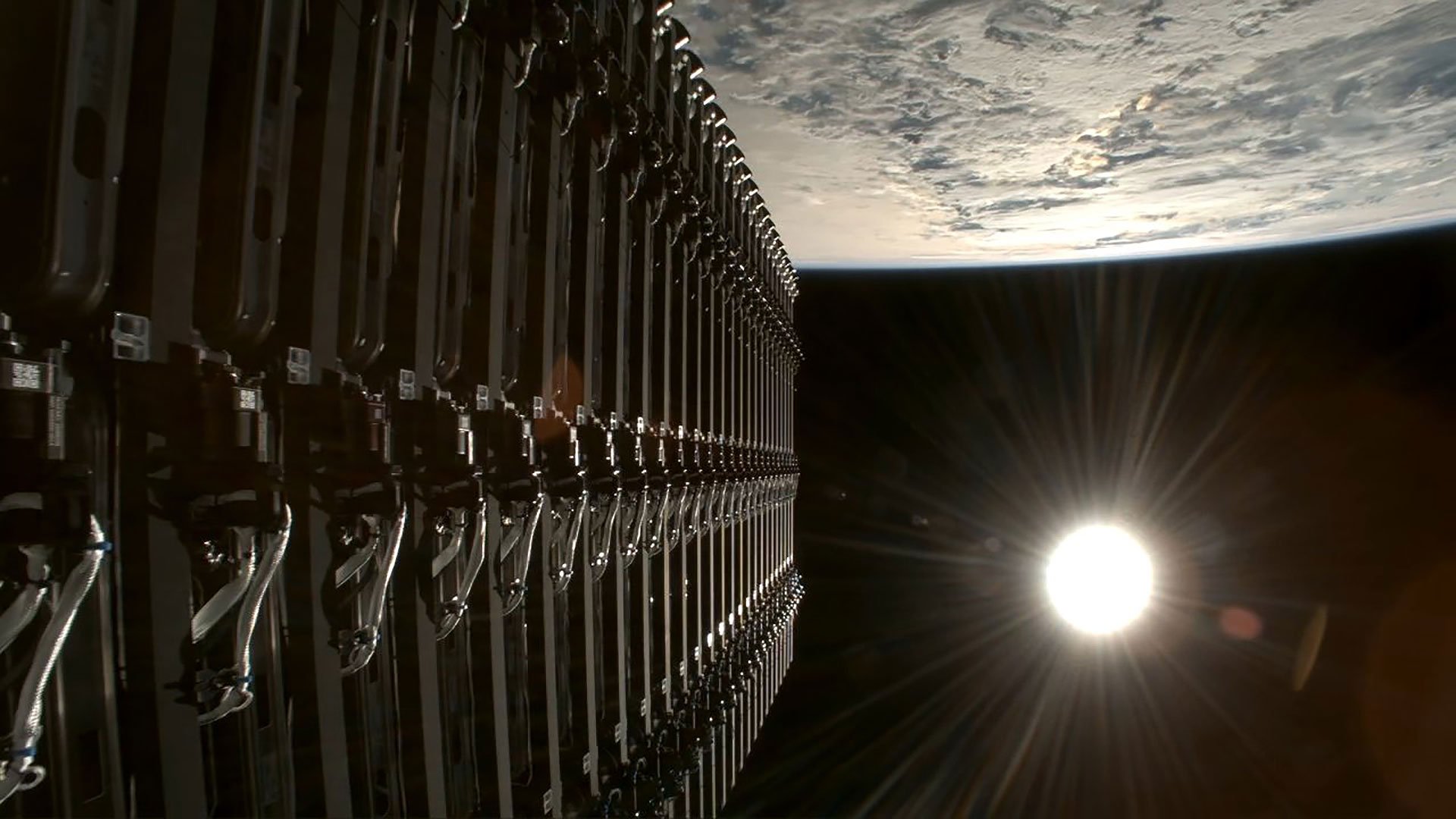

SpaceX is preparing for a significant orbital adjustment. The company announced that it will lower the orbits of approximately 4,400 Starlink satellites—roughly half of its current operational fleet—from their current altitude of about 550 kilometers (342 miles) down to approximately 480 kilometers (298 miles). This migration is scheduled to occur over the course of 2026.

The decision, revealed by Michael Nicolls, SpaceX's vice president of Starlink engineering, is rooted in the predictable rhythms of solar activity and the increasing density of objects in low Earth orbit (LEO). As Nicolls explained in a post on X, the move is primarily a response to the approaching solar minimum, the quiet phase of the Sun's 11-year cycle expected around 2030.

During a solar minimum, the Earth's upper atmosphere cools and contracts, becoming less dense. This has a direct consequence for satellites: reduced atmospheric drag. "As solar minimum approaches, atmospheric density decreases, which means the ballistic decay time at any given altitude increases," Nicolls wrote. "Lowering will mean a >80% reduction in ballistic decay time in solar minimum, or 4+ years reduced to a few months."

In practical terms, this means that if a Starlink satellite were to fail and become unresponsive at the higher altitude, it could remain in orbit for years before naturally decaying. By moving the fleet down to 480 km, the atmospheric drag will be significantly stronger, ensuring that any dead satellite deorbits within a few months. This is a critical safety feature, as a failed satellite becomes a piece of uncontrolled debris, a persistent hazard in an already crowded orbital environment.

The second reason for the shift is the orbital traffic below 500 km. While LEO is becoming increasingly congested, the space below 500 km is still relatively less crowded compared to the band between 500 and 600 km, where Starlink currently resides. "The number of debris objects and planned satellite constellations is significantly lower below 500 km, reducing the aggregate likelihood of collision," Nicolls stated. This is a proactive measure to place the massive Starlink constellation in a region with fewer potential obstacles and competing networks.

This orbital adjustment is not a minor tweak. It involves nearly 4,400 satellites, which represents a substantial portion of SpaceX's operational constellation. The company's current fleet numbers nearly 9,400 satellites, making Starlink the dominant operator in LEO, accounting for about two-thirds of all active satellites. The move underscores the scale of operations and the level of precision required to manage such a vast network.

Nicolls also highlighted the reliability of the Starlink system, noting that only two dead satellites are currently in orbit. "Nevertheless, if a satellite does fail on orbit, we want it to deorbit as quickly as possible," he emphasized. This philosophy of rapid deorbiting is becoming a standard for responsible megaconstellation operators, a direct response to the growing concern over space debris, which was famously illustrated by the 2009 Iridium-Cosmos collision.

The broader context is a LEO environment that is under unprecedented strain. Starlink's growth has been explosive, but it is not alone. China is developing two massive LEO internet constellations, each planned to exceed 10,000 satellites. Other players like OneWeb and Amazon's Project Kuiper are also building their own networks. This proliferation raises the stakes for collision avoidance and debris mitigation. A single collision could generate thousands of new debris fragments, threatening the entire orbital ecosystem and potentially triggering a cascade known as the Kessler Syndrome.

SpaceX's decision to lower its fleet is, therefore, a technical solution to a systemic problem. It demonstrates an awareness of orbital mechanics, solar physics, and the long-term sustainability of space operations. However, it also raises questions about the operational costs and complexities of such a large-scale orbital maneuver. Coordinating the descent of thousands of satellites without interfering with other operators or creating new hazards requires sophisticated planning and continuous monitoring.

The move also reflects a shift in industry mindset. Early satellite operators often viewed orbital altitude as a static parameter. Today, with megaconstellations, altitude is a dynamic variable that can be optimized for safety and efficiency. This is a pattern that other operators may be forced to follow as the orbital environment becomes more congested and regulatory pressures for debris mitigation increase.

In essence, SpaceX's planned orbital descent is more than a routine adjustment. It is a calculated response to the physics of our star and the growing human footprint in space. It highlights the intricate balance between expanding connectivity and preserving the orbital environment, a challenge that will define the next era of spaceflight. The success of this migration will be closely watched by the entire space community, as it may set a precedent for how megaconstellations are managed in the decades to come.

Comments

Please log in or register to join the discussion