The Nobel Prize-winning research on C. elegans worms reveals profound insights for robotics and AI, from neural network efficiency to bio-inspired sensing.

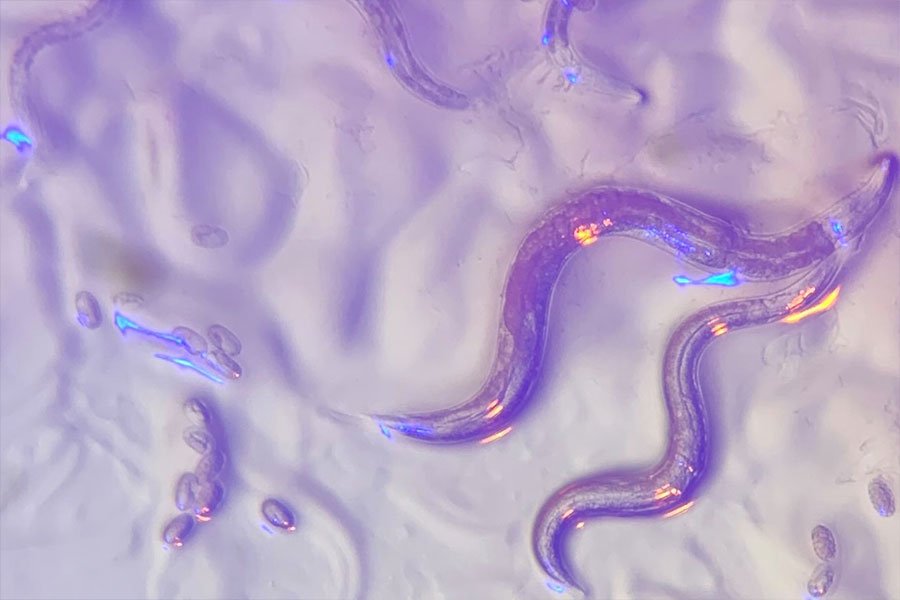

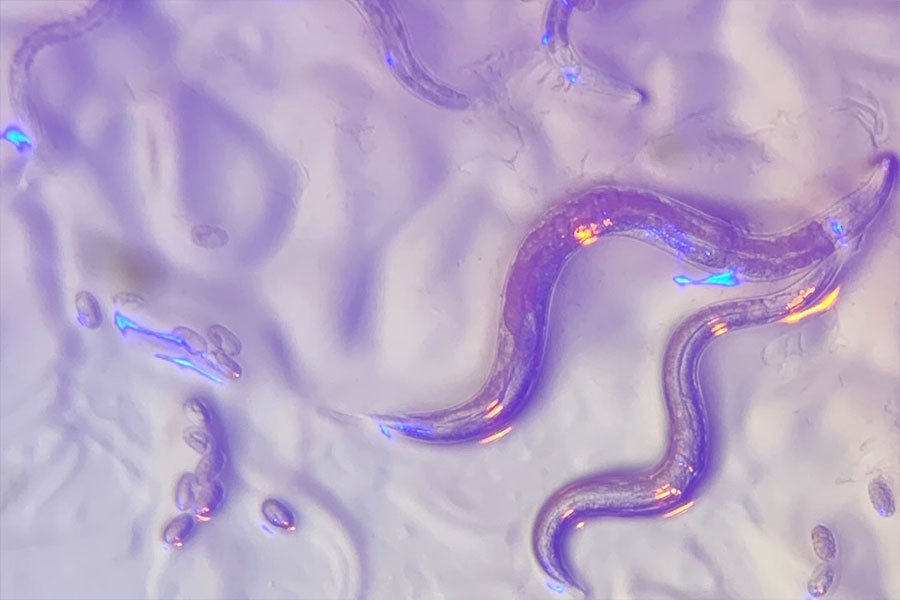

For decades, the millimeter-long Caenorhabditis elegans roundworm has revolutionized biology, earning scientists four Nobel Prizes. But beyond medicine, this unassuming organism offers groundbreaking lessons for autonomous systems, mechanical engineering, and artificial intelligence. Its biological simplicity—a mere 302 neurons, transparent body, and fully mapped neural pathways—provides a blueprint for efficient robotic design.

Neural Efficiency: The Connectome Revolution

C. elegans holds a unique distinction: It was the first organism to have its complete connectome mapped—a wiring diagram of all neural connections. With only 302 neurons, its nervous system processes information efficiently without complex hardware. This feat inspired neuromorphic computing, where engineers design AI chips mimicking biological neural networks. Unlike traditional bulky processors, these systems prioritize energy efficiency, enabling smaller autonomous robots to make rapid decisions. MIT researchers like Steven Flavell now study C. elegans' neural circuits to decode how internal states (like hunger) influence behavior—a model for adaptive robotics.

Sensory Innovation Without Conventional Tools

Remarkably, C. elegans senses environmental color despite lacking eyes or light-sensitive molecules. This capability, discovered through MIT research, occurs through whole-body photoreception. For robotics, this suggests radical sensor design: Instead of relying on power-intensive cameras, future robots could use distributed, minimalist sensors embedded in their structures. Imagine warehouse drones detecting hazards through structural vibrations or medical nanobots navigating tissues via chemical gradients—all inspired by worm biology.

Collaboration Drives Robotic Evolution

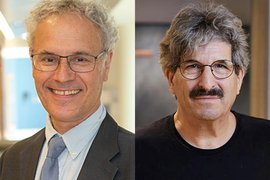

Nobel laureates Victor Ambros and Gary Ruvkun—both trained at MIT—exemplify the collaborative spirit of worm research. Open resources like WormBase (a genetic database) and the Caenorhabditis Genetics Center accelerated discoveries. Similarly, robotics thrives on shared innovation: Open-source platforms like ROS (Robot Operating System) and public datasets enable engineers worldwide to build upon each other's work. This ethos mirrors C. elegans' community-driven progress, proving that collective knowledge propels autonomous systems forward.

Apoptosis and Adaptive Failure Response

Programmed cell death (apoptosis), discovered in C. elegans by MIT's Robert Horvitz, offers unexpected robotic parallels. Just as cells self-destruct to maintain organism health, robots could employ "digital apoptosis" algorithms. If a drone's component fails, the system would isolate and reroute functions—ensuring mission continuity. This biological fail-safe principle enhances resilience in autonomous vehicles and industrial robots.

Future Horizons: Worms as Robotic Architects

C. elegans continues to guide MIT's robotics frontier. Researchers are exploring:

- Temporal Programming: Horvitz's work on how worms transmit timing data to offspring could optimize scheduling in swarm robotics.

- MicroRNA-Inspired Learning: The microRNAs regulating gene activity (discovered by Ambros/Ruvkun) inform adaptive AI that "silences" irrelevant data streams.

- Soft Robotics: The worm's flexible body informs designs for compliant actuators in delicate tasks like surgery.

As AI advances, this humble worm proves that nature's simplest systems often hold keys to our most complex engineering challenges.

Comments

Please log in or register to join the discussion