MCP's remote transport relies on OAuth 2.1 for securing access. This article breaks down the discovery flow, token validation, and the practical trade-offs between dynamic registration and pre-registration for production systems.

The Model Context Protocol (MCP) has rapidly become the standard interface for connecting AI agents to external tools and data. While the protocol simplifies how agents discover and invoke capabilities, it introduces a complex security challenge: how do you verify who is calling your server and what they are allowed to do?

For developers used to securing REST APIs, MCP presents a familiar but distinct set of problems. The protocol separates concerns between the transport layer (how data moves) and the authorization layer (who gets access). Understanding this separation is critical for building secure, production-ready MCP servers.

The Transport Divide: Local vs. Remote

MCP currently supports two primary transports, each with vastly different security models:

Standard Input/Output (stdio): This is a local-only transport. The MCP client launches the server as a subprocess and communicates via standard pipes. Because the client owns the process execution, there is no network-level authentication. Security is deferred to the environment variables passed to the process. If you need an API key for a backend service, you inject it via

ENVand the server uses it. The threat model here is local machine security; if someone can execute the client, they can likely access the environment variables.Streamable HTTP: This is the transport for remote servers. It treats the MCP server as a standard HTTP endpoint. This is where the complexity of network security enters the picture. The specification strongly recommends using OAuth 2.1 here.

This article focuses on the Streamable HTTP transport, as that is where the architectural decisions regarding authentication and authorization matter most.

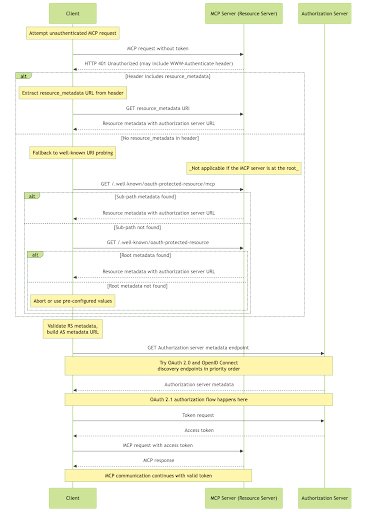

The OAuth 2.1 Flow in MCP

MCP does not reinvent authentication. Instead, it adopts the OAuth 2.1 Authorization Code grant with PKCE (Proof Key for Code Exchange). This is a battle-tested flow designed for user-facing applications.

The flow looks like this:

- Discovery: The MCP client attempts to connect to the server without a token. The server responds with

HTTP 401 Unauthorizedand aWWW-Authenticateheader pointing to a Protected Resource Metadata URL (defined in RFC 9728). This metadata tells the client which Authorization Servers the MCP server trusts. - Authorization Server Metadata: The client fetches metadata from the Authorization Server (RFC 8414) to find endpoints for authorization and token exchange.

- Registration: The client must register itself with the Authorization Server to get a

client_id. - User Consent: The client directs the user to the Authorization Server to log in and consent to the requested scopes.

- Token Issuance: The client receives an access token (and optionally a refresh token).

- Authenticated Request: The client retries the original request to the MCP server, now including the

Authorization: Bearer <token>header.

The Registration Bottleneck

One of the most debated aspects of MCP authentication is client registration. In the traditional web world, this is often a manual step: you register an app in a dashboard and get a Client ID and Secret.

However, MCP agents are often automated or ephemeral. The specification outlines four options for registration, listed here in order of preference:

- Out-of-Band: You manually provision a Client ID for a specific agent. This offers the most control but lacks scalability for open ecosystems.

- Client ID Metadata Documents (CIMD): A newer draft standard where the client provides a URL pointing to its metadata. The Authorization Server fetches this to verify the client.

- Dynamic Client Registration (DCR): The client sends its metadata directly to the registration endpoint (RFC 7591). This was the primary method in earlier MCP specs but introduces security risks if not locked down (e.g., allowing anyone to register a malicious client).

- Manual Entry: The user pastes client info into the UI. This is impractical for autonomous agents.

The Trade-off: Dynamic registration simplifies onboarding for third-party agents but makes it harder to audit who is accessing your system. For enterprise deployments, pre-registering clients (Option 1) is usually the preferred path to ensure traceability.

Scope Design and Step-Up Authorization

Once the token is validated, the MCP server must decide if the token holder is authorized to perform the requested action. MCP scopes (e.g., mcp:read, mcp:write) are carried in the token.

A unique feature introduced in the 2025-11-25 spec is Step-Up Authorization. If a client attempts an action requiring higher privileges than the current token possesses, the server can respond with a 403 Forbidden and a header indicating the required scopes. The client can then trigger a new authorization flow to obtain a token with the elevated scopes, prompting the user for consent again.

This prevents the "super scope" problem where users are forced to grant broad access upfront. Instead, access is granular and requested contextually.

The Downstream Problem: Token Passthrough

A critical architectural gap remains: How does the MCP server authenticate to the backend services it calls?

The MCP spec explicitly forbids simply passing the incoming MCP token through to a downstream API. The downstream API won't know how to validate a token issued by an MCP Authorization Server.

The recommended solution is Token Exchange (RFC 8693). The MCP server takes the token presented by the client, sends it to the Authorization Server along with the identifier of the downstream resource, and receives a new token specifically scoped for that backend service. This maintains the chain of identity: the backend knows the request originated from the MCP server, acting on behalf of a specific user.

Security Considerations

Bearer Token Handling

MCP tokens are bearer tokens. If stolen, they can be used by anyone. Therefore:

- Short Lifespans: Access tokens should expire quickly (minutes to hours).

- Refresh Tokens: Use refresh tokens to maintain sessions without requiring the user to log in repeatedly. Store these securely (e.g., in OS keychains, not plaintext files).

- No Query Parameters: Never pass tokens in URL query strings, as they end up in logs.

Agent-to-Agent Communication

The standard OAuth flow assumes a human is present to consent. What about automated agents or cron jobs? The Client Credentials Grant was removed from the core spec but is returning via draft extensions. This allows a server-to-server flow where the agent authenticates directly with the Authorization Server using its own credentials, bypassing the user consent screen. This is essential for background tasks or AI-to-AI delegation.

Future Directions

The MCP auth ecosystem is evolving rapidly. Current discussions include:

- Rich Authorization Requests (RAR): Allowing more complex, fine-grained authorization requests beyond simple scopes.

- Generic Extensions: A formal mechanism to add features like Client Credentials without bloating the core spec.

Conclusion

Securing an MCP server requires a solid understanding of OAuth 2.1 principles. The Streamable HTTP transport moves MCP from a local tool to a networked service, inheriting all the security responsibilities that come with it.

For builders, the key takeaways are:

- Decide on Registration Strategy: Will you support dynamic registration, or restrict access to pre-registered clients?

- Implement Token Exchange: Do not pass MCP tokens downstream; exchange them for downstream-specific tokens.

- Design Scopes Carefully: Use step-up authorization to avoid over-provisioning access.

By adhering to these patterns, you ensure that the expanding reach of AI agents remains a feature, not a vulnerability.

For more details on the specification, visit the Model Context Protocol GitHub repository. To learn more about the OAuth extensions discussed, see the IETF OAuth Working Group drafts.

Comments

Please log in or register to join the discussion