A deep dive into how a single engineer used thousands of autonomous AI agents to build a web browser from scratch in weeks, revealing surprising insights about parallel software development.

Last week, Cursor published Scaling long-running autonomous coding, detailing their research into coordinating large numbers of autonomous coding agents. One project mentioned was FastRender, a web browser built from scratch using agent swarms. I spoke with Wilson Lin, the engineer behind FastRender, to understand how this experiment in extreme parallel software development actually works.

The conversation reveals something unexpected: in early 2026, a single engineer can orchestrate thousands of AI agents to build complex software at unprecedented scale. FastRender isn't intended as a production browser—it's a research vehicle for understanding how autonomous agents collaborate on massive engineering projects.

What FastRender Can Do Right Now

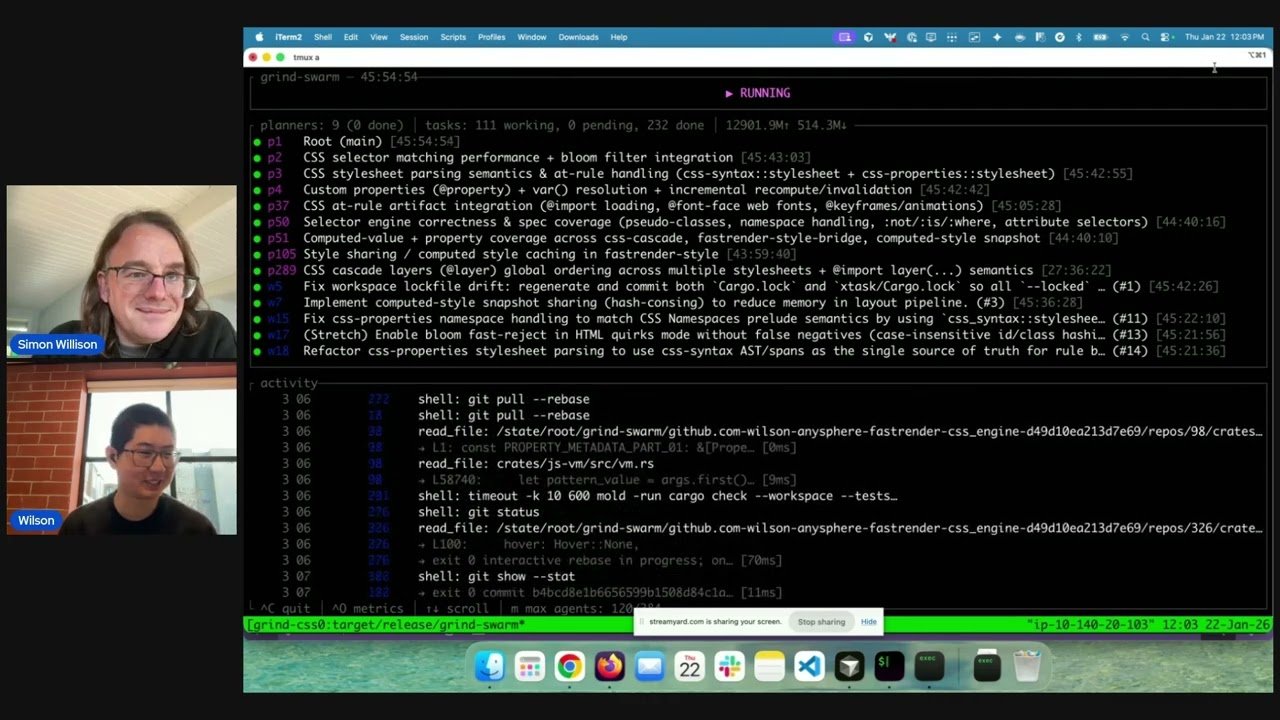

During our demo (03:15), FastRender loaded GitHub, Wikipedia, and CNN. The JavaScript engine isn't complete yet, so JavaScript was disabled by the agents themselves—they added a feature flag to control it (04:02). The rendering is usable but slow, which makes sense given the engine is being built from scratch.

What's remarkable is that these pages render at all. The agents have built enough of the rendering pipeline to handle real-world websites, complete with CSS parsing, selector matching, and layout algorithms.

From Side Project to Core Research

Wilson started FastRender in November as a personal experiment to test the latest frontier models—Claude Opus 4.5, GPT-5.1, and GPT-5.2—on extremely complex tasks (00:56). A browser rendering engine was ideal: it's both ambitious and well-specified, with visual feedback that makes progress obvious.

As single agents showed they could make meaningful progress, the project evolved. It graduated from a side project to an official Cursor research initiative, with resources amplified accordingly. The goal was never to compete with Chrome or produce production software (41:52). Instead, FastRender serves as a testbed for observing multi-agent behavior at scale.

A browser's vast scope means it can serve as a research platform for years—JavaScript, WebAssembly, WebGPU, and more challenges remain for agents to tackle.

Running Thousands of Agents

The most striking aspect is the scale: at peak, the system ran approximately 2,000 agents concurrently for a full week (05:24). These agents produced thousands of commits per hour, resulting in nearly 30,000 total commits to the repository.

The infrastructure was straightforward: large machines each ran a multi-agent harness with about 300 concurrent agents (05:56). Agents spend most of their time thinking rather than executing tools, so the system scales reasonably well.

The agents are organized in a tree structure: planning agents break down tasks, and worker agents execute them (07:14). The browser project was split into multiple workstreams, each running its own harness on separate machines, further increasing throughput.

Avoiding Merge Conflicts Through Smart Planning

With thousands of agents committing to the same codebase, merge conflicts seem inevitable. Yet the system rarely encounters them (08:21). The key is the harness's ability to divide work into non-overlapping chunks. Planning agents carefully scope tasks to minimize overlap, and the code structure reflects this—commits are timed to avoid touching the same areas simultaneously.

This reveals a critical insight for parallel agent systems: if planning agents can effectively partition work, you can scale to hundreds or thousands of agents without coordination overhead.

Model Selection: General vs. Specialist

Surprisingly, GPT-5.1 and GPT-5.2 outperformed the coding-specialized GPT-5.1-Codex (17:28). The agents needed to do more than just write code—they had to operate within the harness, work autonomously without user feedback, and follow complex instructions. General models handled these broader requirements better.

The system runs completely autonomously once given instructions. The longest uninterrupted run was about a week, and Wilson believes it could run longer (18:28). During execution, there's no way to steer or adjust the trajectory—you can only stop it.

Specifications and Feedback Loops

For long-running autonomous systems, feedback loops are crucial. FastRender includes specifications as git submodules: csswg-drafts, tc39-ecma262 for JavaScript, whatwg-dom, whatwg-html, and more (14:06). Agents frequently reference these specs in their code comments.

GPT-5.2's vision capabilities provide visual feedback. The system takes screenshots of rendering results and feeds them back to the model, which compares them against golden samples (16:23). The Rust compiler also provides immediate feedback—compilation errors act as guardrails (15:52).

Agent-Selected Dependencies

The agents chose most dependencies themselves. Some choices were obvious, like Skia for 2D graphics or HarfBuzz for text shaping. Others were more surprising, like Taffy for CSS flexbox and grid layout (27:53). Wilson never explicitly instructed the agents about dependency philosophy, so they selected libraries to unblock themselves quickly.

The agents vendored Taffy and modified it extensively (31:18). In a newer experiment, they're removing it entirely. Similarly, they pulled in QuickJS despite having a home-grown ecma-rs implementation because they needed to unblock themselves while other agents worked on the JavaScript engine (35:15). This mirrors human engineering teams where one engineer might pull in a library to avoid waiting for another team.

Intermittent Errors Are Acceptable

One of the most surprising findings: the agents were allowed to introduce small, temporary errors (39:42). Wilson observed that requiring every commit to be perfect would create a synchronization bottleneck, reducing throughput.

Instead, the system tolerates a stable rate of small errors—API changes or syntax errors that get fixed within a few commits. This trade-off prioritizes progress over perfection, and it works. The errors don't accumulate; they're corrected quickly, maintaining overall system velocity.

This represents a fundamental shift in software engineering philosophy: when coordinating thousands of agents, optimizing for throughput over correctness can be a viable strategy.

A Single Engineer, a Swarm of Agents

FastRender demonstrates the extreme edge of what a single engineer can achieve in early 2026. The project contains over a million lines of Rust code, written in weeks, that can render real web pages to a usable degree.

Wilson notes that the browser and the agent harness were co-developed symbiotically (11:34). The browser served as a measurable objective for iterating on the multi-agent coordination system. FastRender is essentially using a full browser rendering engine as a "hello world" exercise for multi-agent coordination.

Implications for Software Development

FastRender reveals several patterns that may reshape software engineering:

Massive parallelism is feasible: With proper planning, thousands of agents can work on the same codebase with minimal coordination overhead.

General models may outperform specialists: For complex, multi-faceted tasks, general-purpose models can handle the broader requirements better than specialized ones.

Feedback loops are critical: Specifications, visual feedback, and compiler errors create guardrails that keep autonomous agents on track.

Temporary errors enable progress: Tolerating a stable rate of small errors can maintain high throughput in large-scale agent systems.

The engineer's role evolves: Instead of writing code directly, engineers orchestrate agent swarms, focusing on planning, specification, and system design.

The browser is just the beginning. As Wilson notes, the project's scope means it can serve as a research platform for years, tackling JavaScript, WebAssembly, WebGPU, and other challenges.

For those interested in the technical details, the FastRender repository is available on GitHub. The full conversation with Wilson Lin is also available on YouTube, providing deeper insights into the agent coordination system.

This experiment suggests we're entering an era where software development becomes less about writing individual lines of code and more about designing systems that can orchestrate autonomous agents at scale. The browser may be complex, but as a research vehicle, it's proving to be remarkably effective.

Comments

Please log in or register to join the discussion